A carabao and farmer walk in the fields. Photo by Archie Binamira.

In the Philippines, it is not difficult to find a story about resourceful Filipinos who resiliently wade through flood waters and stay strong amidst adversity.

The same could be said for our farmers, who are on the receiving end of typhoons, droughts and other long-term effects of climate change.

The importance of agriculture and farming in the Philippines cannot be emphasized enough. According to the International Institute of Rural Reconstruction (IIRR), agriculture accounts for one-third of employment in the Philippines, making it a key sector.

“The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) estimates that the agricultural impacts of climate change would cost the country 26 billion pesos per year through 2050,” the IIRR reported. “Being a developing country, the Philippines cannot afford such big losses. Smallholder farmers are the most vulnerable and at risk to the impacts of climate change on livelihoods, food security, and nutrition in rural areas.”

Faced with these challenges, Pinoy farmers, public school teachers and non-government organizations (NGOs) are now using climate-smart agriculture (CSA) to mitigate the effects of climate change in the long run.

The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) describes CSA as an approach that helps to guide actions needed to transform and reorient agricultural systems. CSA practices can effectively support development and ensure food security in a changing climate.

“It is about three things: food security, climate adaptation and climate change mitigation,” according to Rene Vidallo, the Philippine Country Program Director of the IIRR. “Agriculture is affected by climate change impacts, but it is also a contributor to it.”

We’ve listed down a few CSA practices that are currently being adopted in the country, and how they are reducing the effects of climate change:

Multi-layer cropping

Mang Julian Aguilar grows a variety of vegetables through multi-layered cropping in his first farm. (Photo: Angelica Y. Yang)

Mang Julian Aguilar, who has spent almost his entire life as a farmer, owns three hectares’ worth of farms in Barangay Litlit, Cavite. He has been working there since the ‘70s, and has observed and experienced the constant changing of climate.

“There are times when the weather can be very hot. There are other times where it can be very rainy. In the long run, my crops depend on the climate,” Aguilar shared.

He also said that like him, farmers in the area started out as rice farmers who ventured into other crops.

“In the ’70s and ’80s, this entire place was full of rice fields. [As the years went by], we started multi-cropping as we ventured into coffee beans. We thought of multi-cropping because it is a way to ensure that if one crop doesn’t survive, another will.”

Aside from coffee beans–which Aguilar supplies to big companies like Nestle–he has also expanded to other vegetables such as pechay, mustasa (mustard), banana, tomato, chili, papaya and cucumber.

According to the non-profit organization NETZ, multi-layer cropping is a resourceful agricultural technique. It involves planting creeper crops on trellis, over which mature vegetables or trees can be staked.

Native pig farming

“Globally, livestock is the biggest contributor of greenhouse gases at 40.5 percent. In the Philippines, pig production and processing [take up a bulk of GHG emissions],” Vidallo explained, in a lecture to journalists who visited the IIRR in Cavite.

According to a 2019 IIRR brief on Models for Empowering Women Livestock Producers, many consider keeping pigs as an expensive practice. Commercial feeds are costly, are subject to availability, and produce lower quality meat.

However, a group of pig farmers from Guinayangan, Quezon Province were able to find a cost-effective way to reduce GHG emission in raising native pigs.

“Instead of giving our pigs commercial feed, we use feeds made from a mixture of vegetables, water and soil,” said Gloria Macaraig, the President of the Guinayangan Native Pig Association, or GuiNaPig. “We use vegetables like kangkong, papaya, kamote, the stem of the banana, and some salt and sugar. We prefer that type of feed because it is not expensive.”

Macaraig added that more and more women were engaging in native pig farming, because they could easily make the organic feeds inside their homes while tending to other duties.

She shared that she is able to cultivate native pigs with organic feed, while working as a public servant in her barangay.

According to Macaraig, organic-fed native pigs are much leaner and meatier compared to commercially feed pigs. GuiNaPig found out about this when one of its members tried feeding native pigs with commercial feed.

“The pig fed with commercial feed grew really fast. It was sold at about 80 kilos. But the fat amounted to 20 kilos. Because of the quality of native pigs fed with organic feed, they sell more in the market at 150 Php per kilo, compared to commercial pigs at 120 Php per kilo.”

Mulching

Mang Julian picks some chilis from a sili plant growing over a pile of mulching leaves. (Photo: Angelica Y. Yang)

“Another source of GHG is the burning of leaves, a practice that farmers have long gotten used to. It’s very convenient for them, but the burning of leaves contributes carbon [to the atmosphere],” Vidallo stated.

Mang Julian Aguilar’s second farm, a vast expanse of trees and root crops, has benefited from mulching. Mulching is the re-integration of fallen leaves back into the soil by decomposition. The decomposed leaves act as a natural fertilizer that is neither expensive nor harmful to the environment.

“To prevent the soil from drying, we ‘mulch’ the leaves. It helps with the moisture,” Aguilar explained.

Vidallo added that mulching is more effective during the rainy season.

“It means that there is a lesser need for Mang Julian to apply [commercial] fertilizer. The lesser the fertilizer, the lesser greenhouse gas emission. This contributes to the national target of reducing emissions,” he said.

School gardens

Marie Ann Galas talks about how Tinabunan Elementary School and other neighboring schools find joy in “exchanging seeds” of different crops. (Photo: Angelica Y. Yang)

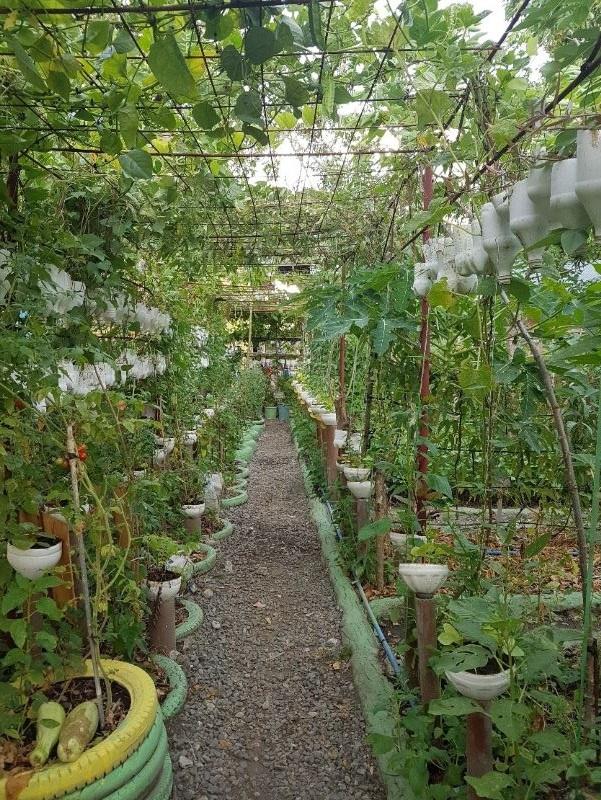

What better way is there to introduce farming and agriculture to kids than to have them experience it firsthand in a learning environment? That’s what Tinabunan Elementary School in Imus, Cavite, is doing.

The public school is very proud of its garden and greenhouse, with both being “learning laboratories” for its Gulayaan sa Paaralan (GFP) program for elementary students.

“The beauty about this is its extension to the community. Many children and even their parents are interested in planting vegetables in their own homes. There was even a case when a kid asked for some seeds from the teacher, so he could plant it in his home,” shared Marie Ann Galas, the school’s garden coordinator.

Galas said that the children’s exposure to agriculture at a young age makes them appreciate it all the more. She believes that interacting with plants at school educates the children in the process.

One of the pathways that snake through the extensive Tinabunan Gulayaan sa Paaralan Crops Museum. (Photo: Angelica Y. Yang)

Healthy feeding program

The school uses the vegetables from its garden to sustain its feeding program for malnourished students.

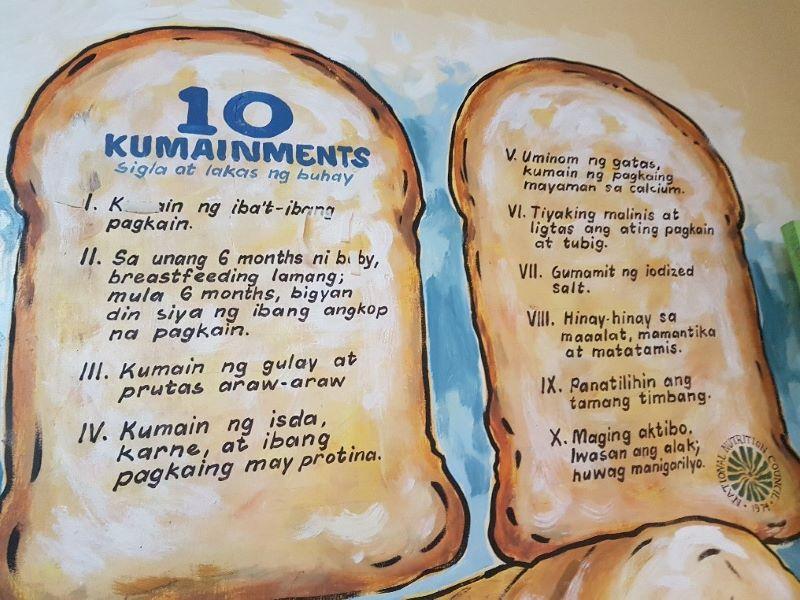

Every day, the school holds the feeding program inside a colorful pink cafeteria with small benches and wall paintings that promote healthy eating.

The food pyramid for kids overlooks the small benches where Tinabunan Elementary School beneficiaries eat their healthy lunches. (Photo: Angelica Y. Yang)

“The feeding program helps our kids,” said the school’s principal, Jesus Borgado. “During the school year 2016 to 2017, there were about 200 kids. At present, there are only 9 [malnourished] kids. The number went down because of their knowledge of the benefits of vegetables from our GFP program.”

The 10 “Kumainments” are painted on the wall of the cafeteria where the Tinabunan Healthy Feeding Program is held. (Photo: Angelica Y. Yang)

According to Borgado, because of the kids’ clamor for vegetables in their packed lunches, parents are now incorporating them into every meal they make, instead of the usual hotdog and rice.

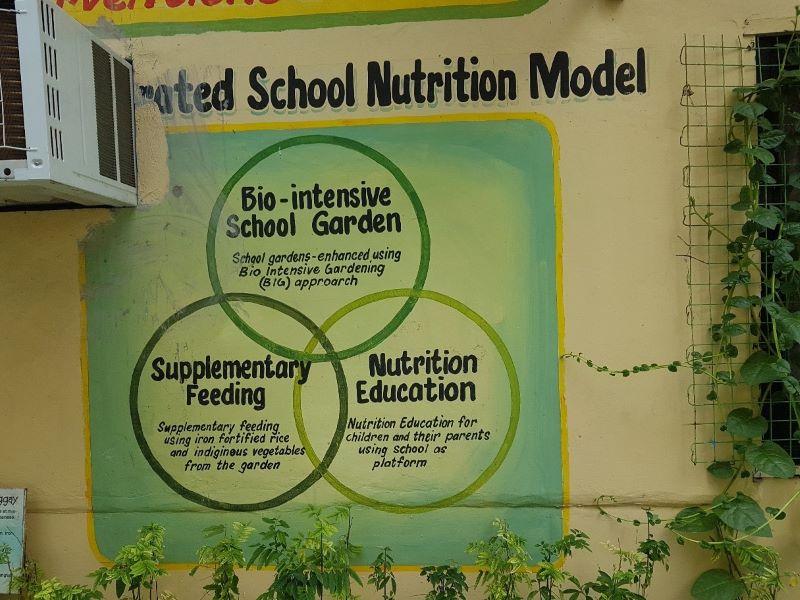

Thanks to the school’s GFP and feeding programs, the IIRR named it a ‘Sentinel School’ in 2016.

The Tinabunan Elementary School, an IIRR-recognized Sentinel school, follows the Integrated School Nutrition Model. (Photo: Angelica Y. Yang)

Sentinel schools are pioneers across Region IV-A in integrating the school nutrition model. It is a three-pronged approach towards addressing malnutrition among school children through gardening, supplementary feeding and nutrition education. —MF

This article first appeared in www.flipscience.ph. Read it here.

The field trip was organized by VERA Files as part of the project supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, which aims to empower journalists from developing countries to cover the environment more effectively.