Paul Hutchcroft at the launch of Asia Foundation’s ‘Strong Patronage, Weak Politics: The Case for Electoral System Redesign in the Philippines’.

American voters usually choose between a Democrat and a Republican, representing the two major political parties that have shaped politics in the United States for over 150 years with their distinct platforms, ideologies and programs.

In the Philippines, which borrowed many political traditions from its American colonizer, voters in the upcoming May 2019 elections will have to choose among 18 parties vying for 12 senatorial seats, as well as a staggering 134 parties battling for 59 party-list seats in the House of Representatives.

While some would argue that this is a sign of how vibrant Philippine democracy is, Australian National University political science professor Paul Hutchcroft thinks otherwise.

“The quality of democracy is undermined by the weakness of parties and, hence, the lack of clear structure to political competition,” he said at the launch on Feb 11 of ‘Strong Patronage, Weak Politics: The Case for Electoral System Redesign in the Philippines’.

“And this is particularly disadvantageous to the poor and marginalized, who are especially reliant on collective action to promote their interests in the policy realm,” he added.

Hutchcroft, who has studied Philippine politics since the martial law era, was among the speakers at the launch in Quezon City. The book was published by The Asia Foundation and Anvil Publishing Inc.

He also wrote a chapter in the book, which examines the problems with the country’s electoral system and the ways that it could be reformed.

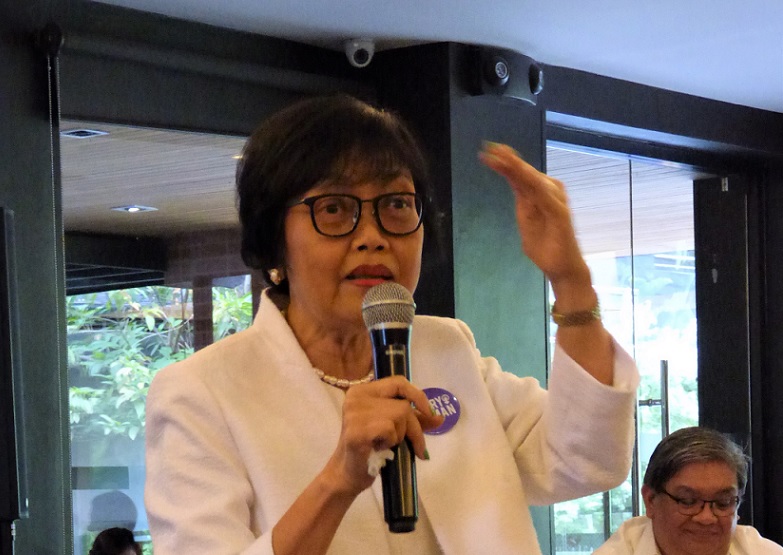

Socorro Reyes, Center for Legislative Development Gender and Governance Adviser

Weakness in numbers

An electoral system is the method used to convert votes into seats. The Philippines uses the plurality system, where the candidate with the most number of votes gets the seat.

The country also has a unique party-list system, where each voter chooses one among hundreds of party-lists that are supposed to represent minorities and special-interest groups like laborers and farmers. However, no party-list may get more than three seats in the lower house.

Hutchcroft noted three major problems with these systems:

- The multi-member plurality system, which is used to elect four out of five Philippine officials, “guarantees” intense competition within a party, thus creating “candidate-centric rather than an a party-centric polity.”

- The president and vice president (as well as governors/vice governors and mayors/vice mayors) can come from different political parties, thus creating “a high degree of incoherence at the top” and more candidate-centric politics.

- The lack of proportionality of the party-list system leads to “a high number of small and ineffectual parties.”

This hodge-podge of parties, Hutchcroft argues, inevitably harms voters.

“Philippine political parties rarely pay much attention to their platforms (if in fact they even bother to write them up) and membership in a political party provides few clues as to what policies candidates may choose to pursue once they are in office,” he said in his chapter of the book.

“As voters often struggle to detect substantive policy differences among those who are listed on the ballot, it is no surprise that their choices are instead often heavily influenced by the material resources that are doled out at election time,” Hutchcroft added.

‘Gold standard’

Some of the book’s authors suggest a “gold standard of party strengthening” known as the closed-list proportional representation system (CLPR), where parties choose and rank the candidates on their party-list, as well as receive seats proportional to the number of votes.

“By binding candidates to parties and requiring voters to cast votes for parties rather than candidates, CLPR is an excellent means by which to ensure higher levels of party cohesion,” Hutchcroft said.

Socorro Reyes, Center for Legislative Development Gender and Governance Adviser, who also contributed to the book, said a zipper-style closed list could allow more women to enter politics.

The zipper arrangement alternates male and female candidates in the ballot, which cannot be changed by the voter or the party.

“This means that the political party cannot move women down the list and move men up if it only receives a small percentage of the votes and consequently only a few seats,” Reyes said in her chapter.

(From L-R) COMELEC Commissioner Luie Tito Guia, political analyst Socorro Reyes, Australian National University political science professor Paul Hutchcroft and political analyst Ramon Casiple

The problem with federalism

Hutchcroft likewise wrote that federalism, which the Duterte administration has been pushing since 2016, may not be the best way to resolve weak parties.

“A shift to federalism, paradoxically, requires a strong and capable central government able to enforce the rules by which authority is being devolved to the subnational level,” he said.

“Given the ongoing weakness of the Philippine state, at the national and more especially the subnational level, the only thing that is safely predictable is unpredictability,” Hutchcroft added.

Critics have also slammed the House’s draft federalism charter for not having provisions against political dynasties and for lifting term limits, which further entrenches politicians in power.

Hutchcroft said electoral reform would have “the highest degree of efficacy with the lowest risk of unintended consequences.”

Important but difficult

Commission on Elections (COMELEC) Commissioner Luie Tito Guia praised the book, saying that learning about alternative electoral systems is very important in solving the problems with the current system.

“Coming from an institution which is the favorite punching bag about politics, this book explains how we operate in a very dysfunctional electoral system,” he said in a speech at the launch.

“Even senior officials, commissioners of COMELEC are not as familiar to alternative electoral systems, which can actually have a more direct impact on making our politics more responsive to the people,” Guia added.

Meanwhile, political analyst Ramon Casiple said in a speech at the same forum that implementing these changes could be difficult, especially with reform measures like the Political Party Development Bill remaining stagnant since 2002.

“The politicians know that the rules must change,” he said. “In my own experience in the past 17 years, those who hold the power, the incumbents, have only given lip service to political party reforms, for obvious reasons. Changing the rules may not exactly favor them.”