On the morning of Jan. 12, 2018, Justinne Mariflor Sarmiento was on her way to Paco Park with her classmates. They were walking to the park to attend a school activity.

But Justinne never made it to the event. The 16-year-old was hit by a 14-wheeler trailer truck as she was crossing the street. She suffered serious head injuries. At around noon of the same day, the grade 11 student passed away at the Manila Medical Center.

Justinne is only one of the many school children who have died on Philippine roads. Last October, Ricardo Cajife took his last walk to his school in the province of Samar. The 13-year-old was hit by an ambulance and killed on the spot. In 2010, Amiel Alcantara failed to come home from his school, the Ateneo de Manila University. He was in the parking lot when a driver rammed into him. The 10-year-old boy died in the crash.

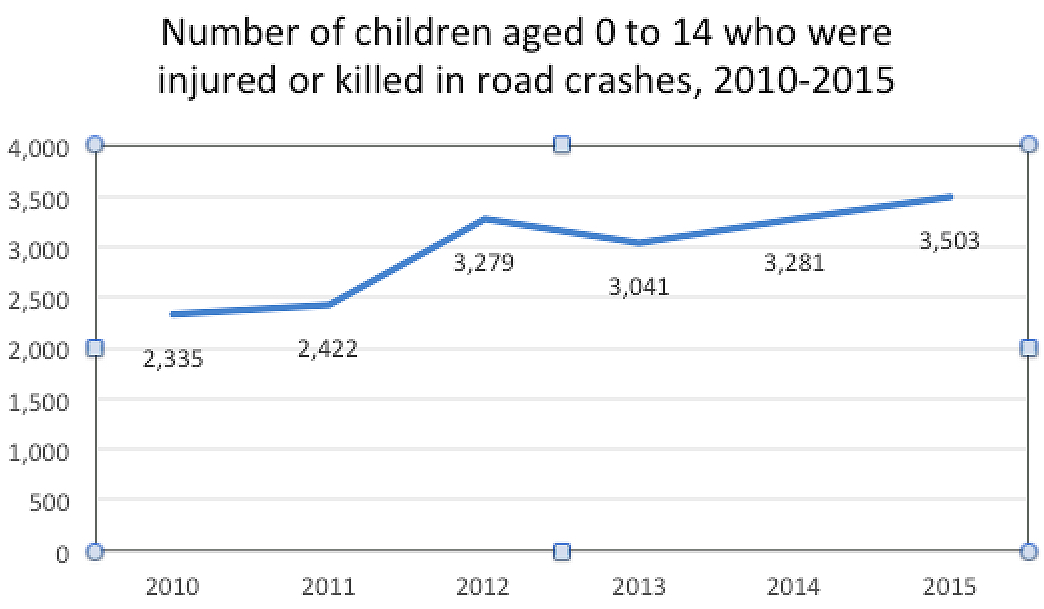

How many school children are killed on the country’s roads? It’s hard to get an exact figure. Yet it is certain that they are exposed to road crash risks. From 2010 to 2015, the number of children aged 0 to 14 who were injured or killed in road crashes has steadily increased.

Source: Department of Health (DOH) Comparative Annual Online Electronic Injury Surveillance System (ONEISS) Report on “Road Transport/Vehicular Accident Cases” for calendar years 2010 to 2015 ( The data in ONEISS is based only on reports to DOH that come from less than 20% of hospitals nationwide).

And just think: Every day, as many as 23.5 million children in kindergarten, elementary, and high school travel to and from school. Multiply the number of school children by two trips a day. That comes out to a mind-boggling 47.1 million chances a day of these kids getting hurt or killed in a road crash.

Their small, frail bodies are mere cat’s whiskers away from death, too many times in a day. Many children travel to schools located right along the highways where motorists speed. They walk where sidewalks and pedestrian crossings don’t exist. They ride motorcycles without wearing helmets. They pedal bicycles where there are no protected lanes to serve as buffer zones between them and speeding vehicles. Or they ride the shaky contraptions that pass for public transit in this country.

How do we keep children safe as they travel to and from school every day? Here’s what four experts have to say.

Teach school children and their parents road safety skills

Ma. Sheilah G. Napalang, D. Eng., En. P., is the director of the National Center for Transportation Studies at the University of the Philippines, Diliman. The center has developed a road safety for children teaching kit. The kit aims to supplement the teaching module on road traffic safety for children at the Grade 6 level.

Education is key to keeping school children safe on the road. In Japan, for example, young kids attend traffic safety classes. There they learn about a car driver’s dangerous blind spots by going around actual cars.

The children are also taught to raise one hand when they cross the street to be more noticeable to drivers. I saw my Japanese professors do that. It’s a habit that was formed when they were young. And that habit is something I’ve taught my 18-year-old son, along with the caution for him to cross only at zebra crossings.

Parents should also be taught about road safety. I have seen parents who walk with their children while the little ones are on the danger side, the side facing the traffic. Children aged six, seven years old are very active and have no concept of consequences and of death; they might dash across the street without checking for oncoming traffic. To keep them safe, parents should hold their kids tightly by the hand and keep them on the safe side, the side away from the traffic.

They can do a lot to keep their children safe. When the kids walk, they need to be visible at all times. Parents can make their children wear colored vests so that they can easily be seen; orange is a good color. Also, they shouldn’t allow their kids to wear headphones while crossing the street so that they can hear the traffic.

When traveling in cars, parents should make sure that no one below seven years old is seated in the front seat. Children should be seated in the back seat and wearing age-appropriate car seats. When traveling on motorcycles, parents should put helmets on their children’s heads.

Parents should also teach their children that when the kids get off the bus, they should not immediately cross the street. Since children are small, they are not easily seen by drivers. So, when the kids alight from the bus, they should stay at the curbside; only after the bus has left should they cross at the crosswalk. And, whenever possible, they should cross the street with an adult.

Put bicycle helmets on kids’ heads

Joel Uichico is the president of Bikes for the Philippines Foundation. Since 2011, the organization has been donating second-hand bicycles to poor Grades 7 to 12 students living in rural areas. As a result, they can keep going to school and gain an education.

To help kids stay safe on the road while they’re on their bicycles, we supply brand-new helmets and bicycle training. Wearing the helmets is part of the contract that Bike for the Philippines signs with the school and the contract between the school and the parents. The children must wear the helmets whenever they ride their bicycles. If the schools want the bikes, they must implement the ‘no helmet, no ride’ rule.

There is much preparation before the bicycles are donated. We meet with the parents, students, school staff, and local officials. There is also an assigned bike coordinator, usually a school teacher who serves as the focal person between Bikes for the Philippines and the school. He or she will monitor the use of the bikes as well as the academic performance of the students.

The choice of who monitors helmet wearing depends on the bike coordinator. He or she enlists the help of the class advisers and the entire school, even the security guard. It’s not an easy task, given that there are 80 to 100 beneficiaries in each school.

I’ve seen some of the beneficiaries fall during the training and get scratches and bruises. But since they were wearing helmets, their heads were protected.

There have been crashes, involving two students who were not yet ready to be given bicycles. Praise God that we have had no deaths.

I did hear of a boy in Pangasinan, though, someone who was not a beneficiary, who was biking at night. He fell, hit his head, and died. This kid was not even going fast, but he was not wearing a helmet.

We immediately shared this sad story with all the bike coordinators so that they can remind the children of the benefits of wearing helmets. We don’t want such a crash to happen to our beneficiaries. You cannot mend the head. We also don’t allow the kids to ride at night because the bicycles are only for school use.

The bike training was designed by Parabanne and Athena Mendoza. They are athletes who have represented the country in international mountain biking events. They taught the children how to safely ride their bikes and use hand signals.

During the training, the children are measured for proper bicycle fit. There should always be some clearance between the top tube and the rider’s crotch: 1 inch for road bikes; and 2 inches for mountain bikes. We also survey the roads where the beneficiaries will bike so that we can assign the right bike to them. This is part of bicycle safety and the proper use of bike.

Lastly, we designed a bike maintenance and repair seminar for the beneficiaries and the school heads. We also donate tools and a pump as well as assorted spare parts. This makes sure that they maintain their bicycles and also ensures safety.

Set speed limits and enforce them at the local level

Sophia San Luis is the executive director of ImagineLaw, a non-stock, non-profit public interest law organization. Atty. San Luis manages the organization’s road safety project on speed enforcement.

To prevent fatal road crashes involving children, the best place to start is speed management. Note that the limit of human tolerance to impact is much lower in children as they are much smaller than adults. This means that to protect children, we have to lower the impact they have to absorb in a crash. The best way to do that is by lowering the speed of vehicles.

There are many ways to slow down motor vehicles. The World Health Organization (WHO) launched SAVE Lives: a road safety technical package, which includes recommendations on effective speed management. These recommendations include setting and enforcing speed limits; installing technologies like speed limiters in cars to help drivers keep to speed limits; and designing roads that would calm traffic.

Of these three recommendations, speed limit setting and enforcement is the most effective for a low- and middle-income country like the Philippines. It is easier to adopt and less costly compared to the other two.

Local government units can set a speed limit of 20 kph within a one-kilometer radius of the perimeters of schools. They can install pedestrian lanes and other road infrastructure—such as speed bumps or rumble strips—to slow down the vehicles that pass near schools.

We at ImagineLaw have collaborated with the Department of Transportation (DOTr), the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH), the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG), the Land Transportation Office, and the Metro Manila Development Authority. We have developed a Joint Memorandum Circular No. 2018-001, or the “Guidelines and Standards for Classification of Roads, Setting of Speed Limits under Republic Act No. 4136 and Collection of Road Crash Data.”

The joint policy has been signed by the department secretaries of DOTr, the DILG, and the DPWH. It prescribes that LGUs classify their roads and set appropriate speed limits according to the road classification.

The Joint Memorandum Circular will be accompanied by a template speed limit ordinance to help local government units quickly enact their speed limit ordinances. If enacted, speed limit ordinances following our template can be implemented immediately. It already contains provisions assigning a lead agency and mandating the installation of signs and procurement of speed guns.

School communities: Take the lead in tackling road safety issues

Greg Smith is the managing director of strategic projects of the International Road Assessment Programme. iRAP is a UK charity that is dedicated to saving lives through safer roads.

It’s hard to encourage people to change their behavior on the road without enforcement. Enforcement can be done by the police. But it can also be done by the school community itself that is taking ownership of this issue.

For example, you might have a community in the Philippines where they decide that vehicle speed is a problem around their school. So the school principal may decide to write a letter to name and shame the parents who drive too fast.

It’s important when enforcement is happening to explain why it is important. If the principal says, from now on we will name and shame the parents who speed. The reason we’re doing that is because when speeds get above 30 kilometers per hour, our children are at risk of death. That messaging could work. Then that school can take pride in managing its own road safety problem.

School communities can also engage in road safety by talking to the road authorities about the infrastructure—such as sidewalks and pedestrian crossings—that they have on their roads. The road department often has a lot on its plate; unless someone tells them here’s a specific problem and here’s a specific solution at this location, often they won’t have a chance to consider it.

That’s where the Star Rating for Schools app could be helpful. It’s an app iRAP is developing that lets the community and the NGOs record the road conditions around their schools, particularly where the children walk and where they cross the road. The iRAP Star Ratings are an internationally recognized measure of risk on roads; the least safe roads are rated as 1-star and the safest as 5-star.

Using the app, the community and the NGOs can identify the Star Rating for the road and then talk to the authorities about what could be changed at those locations to improve the rating. In the Philippines, there’s a special road safety fund that is paid for by the Motor Vehicle User’s Charge. So, when the community and the NGOs bring the results of their study to the authorities, they can refer to that fund. Once you give them a tool like the Star Rating for Schools app to help express that, people become good advocates for what needs to be done at their own location.

If the road authorities take the time to look at the study, they’ll see that it’s a solution for the school and for the authorities. After all, they do want to improve the road in constructive ways.

We at iRAP want the app to be as simple as possible. It is still being tested in Latin America, the U.S., Vietnam, and Africa. In some places in Africa, it has led to the construction of improvements. In the next six months, we should be able to have the app up and running for NGOs in the Philippines to use.

Dinna Louise C. Dayao participated in the 2016 Bloomberg Initiative-Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the WHO, the Department of Transportation, and VERA Files. She completed the Global Road Safety Leadership Course in March 2017, organized by the Johns Hopkins International Injury Research Unit, Global Road Safety Partnership, and Bloomberg Initiative for Global Road Safety. Dayao’s road safety reporting has also been supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

This story was produced under the Bloomberg Initiative Global Road Safety Media Fellowship implemented by the World Health Organization, Department of Transportation and VERA Files.