Almost 30 years ago, a powerful typhoon caused floods and landslides

that swept away homes and entire families in Ormoc City. When floodwaters subsided,

bloated bodies, logs and other debris were strewn everywhere.

In the light of the spate of typhoons that devastated many parts of the country, VERA Files

is re-publishing a two-part story on the Nov. 5, 1991 disaster that killed at least 6,000 people,

and how the communities and the government rose from the tragedy and learned how to tame

nature’s wrath.

This was first published in April 2019

(First of two parts)

ORMOC CITY- At dusk, children of varied ages play on a promenade-like embankment for flood control along Anilao River, oblivious to the tragedy that befell residents here some 28 years ago.

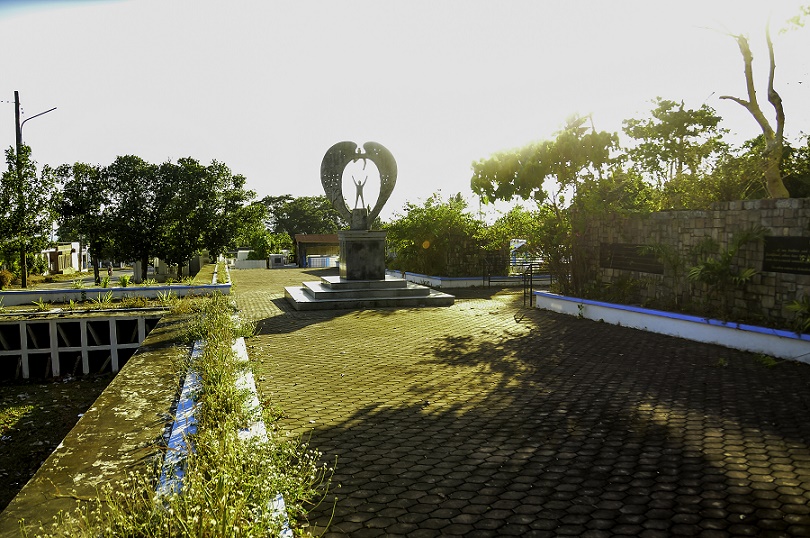

There is a reminder though of what happened on November 5, 1991 that claimed more than 6,000 lives. At the Ormoc City public cemetery where some 4,900 victims of the flash flood were buried in a mass grave, there’s a monument depicting a soul lifting its hands to an angelic figure whose wings are shaped like trees.

An angel statue stands at the mass burial site of the victims of the 1991 flash flood. Photo by Liza Macalandag

On a stone wall, words in gold on black granite say, “In loving memory…of our brothers and sisters who perished during the November 5, 1991 flash flood, whose lives have been lost by the dreadful wrath of nature; a painful event, but a crucial reminder of our obligations in the care of the environment. For when nature is disturbed, it strikes back in fury and spares no one.”

Some survivors are still haunted by images of that fateful day when a rampaging mix of mud, debris and logs swept their houses, kin and neighbors to the Ormoc sea. The deluge came after three days of heavy rainfall brought by typhoon Uring (international name Thelma), which caused massive flooding and landslides in the Eastern Visayas region.

Robert Colo, a 35-year-old tricycle driver who was seven years old then remembered the water reached up to his neck, and the current was so strong he had to be carried on someone else’s shoulders.

When the floodwaters subsided, Colo saw bodies strewn in front of the church and the current site of the plaza. He said prisoners temporarily released to help in the disaster threw bodies from the side of the road to the trucks, to be brought to a mass grave.

The little pathways in the villages were filled with muddy water and people tied themselves to ropes attached to posts so they would not be swept away by the current. Because their house was on higher ground, near the high school site, Colo’s family survived. Those on or beside the river in Isla Verde village, were “wiped out, many swept to the sea unrecovered.”

Amid the devastation, surviving Ormoc residents washed clothes and other belongings even as they continued searching for relatives and burying the dead.AP Photo by Boy Cabrido.

Officials attributed the heavy death toll to a combination of factors including the unusually heavy rain and the presence of informal settlers along the riverbanks.

City Planning and Development Office head Raoul E. Cam said studies by the Department of Environment and Natural Resources revealed the intense rainfall impounded water upland. With the soil’s capacity to hold rainfall breached, water rushed down, gathering debris and logs along its path to Anilao and Malbasag rivers.

Ciriaco Solibao III, head of the city’s Disaster Risk Reduction Management Office, also said the physical features of Ormoc renders the place vulnerable to flooding.

The Ormoc Ecological Profile (2015) says that “the city core is approximately 5 to 8 meters above sea level and 855 m below the peak of the watershed of the two major river systems, Anilao and Malbasag, that drain into the city center.” It is “like a funnel where these two rivers converge,” directly affecting six barangays.

“The risks and hazards due to flash floods are further aggravated by the degradation of the watershed area, and the presence of settlements along the Anilao and Malbasag Rivers and the Ormoc Bay, which serve as the final discharge area of these two rivers,” the ecological profile said.

These days however, those traumatic memories have somehow receded to the background. There’s a pervading sense of confidence that the effective flood mitigating measures instituted by the city government will ensure that the city, bustling with life and commerce, would not see a disaster of such magnitude again.

Now a first class, independent component city not subject to regulation by the Leyte provincial government, Ormoc has been recognized for “catalyzing global solutions to the climate crisis by making urgent action a necessity across every level of society.” It has a Local Climate Change Action Plan (LCCAP 2016-2025) formulated through USAID technical assistance.

Survivor Robert Colo, 35, tricycle driver was six years old at the time of the flood. Photo by Liza Macalandag

Ormoc City Mayor Richard Gomez recently received the Allen S. Quimpo Climate Leadership for Governance Memorial Award—“for advancing climate action and promoting renewable energy.” He also committed not to establish coal-powered plants in the area.

Moreover, the city implements environmental policies like “No Plastic Day” on Wednesdays and an ordinance requiring rainwater harvesting facilities in new buildings. The city also co-hosts the world’s second largest geothermal steam field.

To top it all, Ormoc City has been considered “richest” among seven cities in the Eastern Visayas region based on the 2017 Annual Financial Report for the Local Government released by the Department of Finance in November 2018.

With its P5.9 billon assets, Ormoc had overtaken the P3 billion total assets of the region’s administrative center Tacloban. The city now hosts two malls which opened in 2018—Robinson’s Place Ormoc and SM Center Ormoc.

The city gripped by disaster in 1991 has apparently bounced back. Its vision, according to the city’s Comprehensive Development Plan (CY 2017-2023), is to be the “agro-commercial and industrial gateway in Eastern Visayas, and the renewable energy capital of the Philippines with a growth inclusive economy, in a disaster resilient environment, administered by an accountable local government.”

In the light of apparently successful moves made after the disaster —technical mitigating structures on the rivers, the watershed ecosystem, and overall disaster preparedness — Vera Files revisited the site. Local government officials shared hard lessons learned.

Children playing along Anilao River, unaware of the tragedy in that very same place 28 years ago. Photo by Liza Macalandag

A 1992 study by the Environment and Research Division of Manila Observatory stated the mistakes of the past:

First, “the probability of flood occurrence” in Ormoc’s (or any) lowland area is governed largely by the condition of the upland ecosystems. This makes it “a prime necessity to restore the stability of these ecosystems,” including ensuring forest cover of watersheds, changing land use patterns and control, and the manner of cultivating slope areas.

The estimated 500 mm of rain that fell over Ormoc watershed on November 5, 1991 – or 167 mm per hour — was “far beyond the absorptive capacity of the soils in the watershed” whose cover that time was 60 percent newly plowed sugar cane fields, 25 percent cogon, and 15 percent corn or bare sloping ground.

Large tracts of land with slopes greater than 18 degrees were planted to agricultural crops “even up to 600 meter elevation,” the evaluation report noted. Under government standards, lands with slopes of 18 degrees or more are automatically considered forest lands unsuitable for agricultural purposes.

Second, the hazard of flooding may also be increased by conditions within the lowlands. “Unless the stability of the upland is complemented by proper planning and management of the lowland, the hazard of flooding will persist,” the same report said.

In the case of Ormoc before the flooding, urban development had changed the drainage and channel patterns, but the flood patterns were not fully taken into account.

Moreover, “the reclaimed embankments of the Anilao River and the floodplain,” then the village of Isla Verde, “were both hazardous” but were “allowed to be densely populated” with informal settlers.

Eleuterio Lugas, 61, broommaker, remembers stepping on bodies which he mistook for banana stalks on the Anilao riverbed after the flash flood. Photo by Liza Macalandag

(Last of two parts)

Revisiting the day of the flash flood, there is a sense that all the elements that could make a disaster happen happened that day.

In the morning of November 5, 1991, Typhoon Uring (international name:Thelma) dumped heavy rains as it moved slowly over Leyte, including the Ormoc watershed. The intense rainfall, which had been going on for several days, triggered a massive volume of water to rampage downstream with debris and land sediments.

The flood lasted just over three hours and inundated a square kilometer of commercial and residential areas of Ormoc City proper.

Floodwater surfaces rose by seven feet in 15 minutes just before noontime, witnesses said. An estimated 22,835,000 cubic meters of water flooded the city.

“The sedimentation that took place doubled the volume of fluid that flooded Ormoc,” according to the Manila Observatory Research (ERD, 1992).

Eleuterio Lugas — a 61-year-old broom maker who was a resident of Biliboy village near the current site of the Anilao slit dam — recalled there was heavy rain with little wind for three days. Then the skies darkened and heavier rain pounded the city.

At first he was happy to gather some coconuts that floated with the onrush of water in the river, but the water rose so quickly that he had run to higher ground. A neighbor and her 11-year-old daughter got swept by the flash flood.

When he walked through the river on his way to Barangay Alegria after the flooding, at first he thought he was stepping on banana stalks, but they turned out to be bodies of children and adults buried in the muddy silt and debris.

Dead bodies are loaded onto a truck. AP photo by Boy Cabrido.

Today, his house made of bamboo overlooks the Anilao slit dam, one of the flood mitigating structures built with the Japanese government’s assistance. He feels confident that if a similar flood comes, the slit dam will stop the debris, logs and silt.

His son-in-law Avelino Aguirre, who worked in the Japan International Cooperation Agency project, said the slit dam structure is made of thick steel with cement poured inside.

Effective Flood Mitigation Measures

The JICA, through a grant, built four bridges and three slit dams between 1997 and 2001 to mitigate floods and landslides in Ormoc.

It likewise facilitated the widening of the city’s main rivers of Anilao and Malbasag, and the relocation of residents from the riverbanks.

Engr. Milany L. Bernal of the City Engineers Office, explained that JICA’s flood mitigation project widened the Anilao and Malbasag Rivers after a measurement of the water volume, flow and pressure found that these were major factors in the flooding.

There are “hydraulic drops” to make the water flow gradually and three slit dams (Anilao, Biliboy and Malbasag) to stop or control the debris and logs carried by the rampaging waters, Bernal explained.

The effectiveness of the JICA structures, she said, were tested during typhoon Gilas in 2003, and typhoon Yolanda in 2013.

She noted, however, that there are problems of “encroachment” near the dam structures despite a fence placed there by the City Engineers Office.

The slit dam at Biliboy, one of the flood mitigating structures built with the Japanese government’s assistance. Photo by Liza Macalandag

The JICA Committee includes the Mayor’s Office, the DPWH and the City Engineers Office whose task is to maintain and monitor the flood mitigation facilities: the three slit dams, the hydraulic drops and the three bridges, said Yvonne de los Santos, also from the City Engineer’s Office.

Part of their task, Bernal said, is to control vegetation on the river, clean canals and river channels, and ensure there are no “encroachers” near the structures.

Both Bernal and de los Santos said the flood control measures succeeded in preventing a flash flood when Typhoon Gilas came in 2003, bringing the same volume and level of water as Typhoon Uring did in 1991.

“The volume of water became manageable with the widened rivers, and the debris got stopped from being swept by the silt and water,” de los Santos noted.

City Planning and Development Office head Raoul E. Cam said his office intends to transform the riverbanks into urban green spaces that people can enjoy as a park and help protect. He said he will push for barangays to be involved in the monitoring and maintenance of the flood mitigating structures.

Recovering forest in watershed

Early morning in mid-March, some 150 student volunteers from Ormoc Senior City High School hiked to Sitio Quarry to plant seedlings of local tree species on a steep watershed area there.

They were guided by some teachers and forest guard Anthony Dionaldo to ensure the seedlings are planted on critical parts of the watershed.

One of the tasks of the city’s Environment and Natural Resources Office (ENRO) is to ensure the recovery of the forest in Ormoc’s watershed, like the one in Milagro, in a step-by-step process, ENRO head Rafael Dumalan told Vera Files.

While there is P5 million allotted for reforestation, he clarified that there is no big project for planting trees. He said they cater to people who belong to organized groups like students in schools, non-government organizations and private entities.

At the time of the flash flood in 1991, of the total land area of the Ormoc watershed, only “3.3% was classified as timberland—confined to the peaks,” a 1992 study of the Environment and Research Division of Manila Observatory said.

The same study noted that “even the residual forest was absent.” At that time, 96.7% of Ormoc watershed was classified as alienable and disposable land, open for private acquisition.

There were more than 700 lot claimants within the watershed, cadastral records show, but “land ownership was held and controlled by just a few big families.” (MO Study 1992).

Rafael Dumalan, head of Ormoc city’s Environment and Natural Resources Office. Photo by Liza Macalandag

Dumalan emphasized the need to plant the appropriate endemic tree species, like bitangkol, lawaan and talisay in watershed areas for the recovery of denuded forests in Ormoc. His office supports a seedling nursery in Milagro village and partners with teachers and students, as well as those under the government’s drug rehabilitation program.

Since 1991, he said municipal government units have facilitated the planting of trees in their watershed areas. His next project involves riparian vegetation, like planting mangroves and bamboos beside rivers.

The idea, he said, is to save the rivers, to make them flow naturally, and continuously ensure the river is not blocked by informal settlers as what happened in 1991.

Forest guard Dionaldo said he and three colleagues work in sitio Quarry watershed, and part of their job is to maintain the reforested areas, water the seedlings if necessary, and report encroachers and tree cutters.

Mark Gerald Talle, 17, a grade 10 student who planted a talisay seedling, said he sees the value of planting trees in the watershed for the future.

The activity is part of requirement for graduating students, teacher Jemo de Asis said. The first batch of student volunteers numbered 300, she added.

The reforestation efforts include awareness campaigns on the importance of protecting the ecosystem, given the undeniable changing climate pattern, Dumalan said.

Many believe the denudation of the forest on the watershed hastened the flooding in 1991 since deep root anchors were absent to hold the water flow.

There is no doubt that the Anilao-Malbasag watershed was the major drainage basin that directly influenced the flooding of the city. The watershed is drained mainly by the Anilao and Malbasag Rivers.

Protecting the watershed ecosystem

DENR 8 Regional Executive Director Crizaldy Barcelo, in a statement released on International Day of Forest, underscored the importance of raising awareness on how sustainably managed forests contribute to the environment.

“Forests secure our soil and water resources, mitigate climate change, and provide habitat for animals and livelihood for human. Its importance cannot be underestimated,” Barcelo stressed.

To intensify the effort, DENR is also implementing a biodiversity protection system using advanced technology called the LAWIN Protection System. Using a mobile application called cybertracker, users and patrollers from the DENR report real-time environmental abuses from the site.

A young boy holds a seedling during a tree planting activity that will help ensure that a tragedy that happened in 1991 will not happen again. Photo by Liza Macalandag

Making proactive moves in disaster preparedness

Ciriaco Solibao III, the head of the city’s Disaster Risk Reduction Management Office, said his office had been organizing the barangays to be prepared for disasters, including leading information and education drives on disaster management for 42 most flood-prone villages.

He said his plans include strengthening the early warning and weather monitoring systems, as well as installing a water level system.

The focus of Ormoc’s disaster management office is not so much evacuations, but pre-emptive action. The rule is to be “pro-active, not just reactive,” Solibao added.

Barangay covered courts are targeted as primary evacuation centers, while schools are last priority, he said. Barangays are encouraged to have two-story halls, and covered courts must be equipped with toilets, bathrooms and cooking areas.

Solibao’s office is also identifying people who may be ready to receive evacuees.

At the 25th commemoration of the Ormoc flood disaster, JICA Chief Representative Susumu Ito observed that Ormoc’s experiences in disaster risk reduction management “show that we can get things done together by raising our understanding of disasters, harnessing available resources, and strengthening community preparedness.”

This story is published by VERA Files under a project supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, which aims to empower journalists from developing countries to cover the environment more effectively.