By YVONNE T. CHUA

IF things go as planned, the Department of Education will start delivering this month 61.4 million copies of textbooks and teachers’ manuals worth P2.58 billion to public elementary and high schools nationwide.

The shipments consist of some 40 titles, both old and new, all of them expected to be distributed by summer. When school year 2012-13 rolls around, every public school child will have his or her own textbook in all the core subjects except in high school Filipino where no books were bought by the DepEd.

But civil society watchdogs as well as several former and current education officials say about half the books, or just over 30 million copies valued at P1.317 billion, were procured by direct contracting, a mode they said violates Republic Act No. 9184 or the Government Procurement Reform Act. The law sets competitive or public bidding as the rule for all state procurements and allows direct contracting only in “highly exceptional cases.”

The transactions involve seven publishers of 18 old titles that have been in use in public schools for almost a decade. And it was Education Secretary Armin Luistro who decided in late April to buy the books through direct contracting. That early, the DepEd’s own Procurement Service reminded the Bids and Awards Committee (BAC) of the violation through a memo.

The contracts for the old titles were “supply and delivery” contracts in which the copyright, printing and delivery were bundled together. They were bought with government money earmarked in the 2010 and 2011 national budgets.

The procurement of these old titles caught the attention of civil society organizations such as the Ateneo School of Government (ASoG), National Citizens’ Movement for Free Elections (Namfrel) and Procurement Watch, which regularly sit as observers in the DepEd biddings.

These groups say the transactions took place alongside those for the new titles to which the DepEd applied its standard practice for regular purchases of textbooks. This practice unbundles the mode of acquisition: direct contracting for the copyright, and competitive or public bidding for the printing and delivery contracts.

A sizable number of the new titles were bought using money from the World Bank, which strictly requires competitive bidding.

Civil society watchdogs and former and current DepEd officials say the P1.317 billion supply and delivery contracts for the 18 old titles marked the first time the DepEd deviated from the 2004 Textbook Policy. That policy was set by then Education Secretary Edilberto de Jesus and required the department to buy textbooks through “national competitive bidding” in keeping with R.A. 9184 and to allow as many parties to compete for contracts in a bid to bring down prices.

But top DepEd officials insist that the transactions are legally defensible. Education Undersecretary Francisco Varela, who chairs the BAC, said RA 9184 in fact authorizes direct contracting as an alternative mode of procurement to competitive bidding for goods of a proprietary nature, such as textbooks that are copyrighted, as long as the head of the procuring entity authorized it.

Varela and Socorro Pilor, executive director of the DepEd’s Instructional Materials Council Secretariat, also said the DepEd had first bought the 18 titles before the adoption of the 2004 Textbook Policy which, they said, applied only to new titles.

A former ranking DepEd official, however, said De Jesus’ policy “applies to both old and new titles.” It had also addressed the copyright problem by paying publishers who held the copyright a fee every time their titles were printed through competitive bidding, and by paying the authors a royalty fee for every copy printed and distributed.

Competitive bidding was designed to promote openness and transparency and involves several stages, including advertisement, pre-bid conference, eligibility screening of bids, evaluations of bids, post-qualification and award of contract.

Direct contracting, also called single source procurement, dispenses with elaborate bidding documents. The supplier is invited to simply submit a price quotation or a pro-forma invoice together with the conditions of sale. The offer may be accepted immediately or after some negotiations.

Namfrel secretary general Eric Alvia said resorting to direct contracting opens the DepEd to criticism that it had failed to foster a “competitive environment.”

“Even if direct contracting is in compliance with the law, competitive bidding would remove the cynicism about the DepEd and suspicions of corruption, favored suppliers, rigged bidding,” he said.

The former DepEd official called direct contracting “a real risk on DepEd’s part” because it has shut out other suppliers for the next three to five years. The newly bought books will be in use for at least three years, according to the DepEd.

Alvia also said the DepEd failed to get the opinion of the Government Procurement Policy Board before undertaking direct contracting to remove all doubts if this method could be used to buy the old titles.

Luistro clarified the Textbook Policy in a June 14 memorandum—DepEd Memorandum 135—which he based on a legal opinion of DepEd Undersecretary for Legal and Legislative Affairs Alberto Muyot.

“Direct contracting for reprinting and replenishment is not expressly prohibited by law,” Muyot said. He also interpreted the competitive bidding required in 2004 Textbook Policy to apply only “to the acquisition of new titles of textbooks and not to those that are already existing and being used by DepEd.”

The 18 titles were among the two dozen the IMCS had first wanted in November 2009 to acquire through an emergency purchase or direct contracting to replace the books destroyed in five regions hit by typhoons “Ondoy” and “Pepeng.” The IMCS had then planned on procuring a far smaller quantity of 3.5 million copies.

These books include Sibika/Hekasi 1 to 6, Math 2 and 6, Science 3 and 6, and Filipino 1 to 6 for elementary and Araling Panlipunan I and II for high school.

A month later, when the books had not been bought and an emergency purchase could no longer be justified, the BAC advised the IMCS to use the normal procurement method for the titles: obtain copyright authorization through direct contracting and hold competitive bidding for printing and delivery. The IMCS agreed.

When Luistro and his team assumed office in July 2010, however, the DepEd still had not bought the books. That November, he approved the IMCS’ recommendation to buy about 25 million copies of the 21 titles, among other titles, to address the growing textbook shortage nationwide. He issued an authority to procure, specifying direct contracting for copyright fees and competitive bidding for printing and delivery.

The DepEd was hoping to buy the copyright for under P3 apiece, given that these were old titles and involved a big quantity. When 2010 drew to a close, it had gotten three publishers—Edcrisch International, Lexicon Press (representing Diwa Scholastic Press) and Rex Bookstore—to reduce the copyright fees to a range of from P1.50 to P2.92, and was already poised to release the notices of award to them. Dane Publishing would also substantially reduce its quotes in the coming months.

But SD Publications stood pat on its P13.86 quote and LG&M Corp. and Vibal Publishing on their P14.85 fees. The three are sister companies and own the copyright to the nine titles the DepEd wanted to buy.

Former and current DepEd officials and civil society observers said, however, publishers should not be charging high copyright fees. “Every publisher produces the books based on the DepEd curriculum. They’re only slightly different. You’re buying the book based on their conformity to the standards. It’s not a novel,” one DepEd executive said.

Public school officials and teachers from Metro Manila interviewed for this report also took issue with some of the old titles. They say these are no longer “aligned” with the curricula that have been revised over the years.

Pilor said the IMCS decided to get the old titles after new titles for three subjects —Science, Math and Filipino—submitted to its “Textbook Calls” failed the evaluation. The last evaluation was held in 2009.

Varela said the DepEd also decided to postpone the Textbook Calls to await the curriculum for the new “K+12” program, which requires schoolchildren to go through Kindergarten and a total 12 years of elementary and high education.

In a move that took the Procurement Service, several BAC members and civil society observers by surprise, Luistro issued on April 25 a revised authority to procure about 37 million copies of the 21 titles worth P1.48 billion through supply and delivery contracts to be awarded through direct contracting.

Varela said the original plan to use direct contracting only to buy the copyright and then bid out the printing and delivery was abandoned after the DepEd could not get all the publishers to budge on the copyright fee.

“Timing was also a consideration. (The problem is what) if you keep negotiating for the copyright and you don’t come to an agreement …We have practically no textbooks in the field,” he said. The department originally wanted the books delivered last October.

To justify direct contracting, the DepEd amended its Annual Procurement Plan (APP) and the IMCS’ Project Procurement Management Plan after Luistro issued his April 25 order to specify this as the procurement mode.

This failed to assuage worries of several BAC members. Assistant Secretary Tonisito Umali, BAC vice chairman, approved the revised APP “except,” he stated in a handwritten note, “for the ‘direct contracting’ as a method for procurement under IMCS. I recommend that we do competitive bidding for printing and delivery for the textbooks and teacher’s manual with the copyright to be negotiated.”

Civil society observers who attended the BAC meeting on May 26 also quoted Umali as saying then, “Direct contracting may be legal but may not be the most advantageous to the government.”

In answer to the Procurement Service’s memo that direct contracting for the supply and delivery of the old titles violated RA 9184, Muyot’s May 31 legal opinion said the law allows direct contracting for books because these are copyrighted and the DepEd’s APP had already identified this procurement method after the original mode, public bidding, could not be pursued.

The DepEd undersecretary also said Luistro is authorized by RA 9184 to resort to alternative procurement methods “to promote economy and efficiency as long as the most advantageous price of the government is obtained and whenever justified by conditions set forth by RA 9184.”

But he also suggested that the department get the GPPB’s opinion “for the further protection of DepEd, its Bids and Awards Committee and other officials.”

Varela said, however, there was no need to consult the GPPB because directing contracting for the old titles “is not a procurement issue.” He said the DepEd instead wrote the GPPB to say it was resorting to direct contracting for reprinting and replenishment of old titles after Budget Secretary Florencio Abad and several GPPB members questioned Luistro’s memo in their August meeting.

On June 21, the day the DepEd decided to award the first three contracts to Alkem Co. (representing Edcrisch), Lexicon and Rex Bookstore, a BAC member asked the ASoG and Namfrel if the committee could insert a provision in the “resolution to award” it was preparing for the three firms that the NGOs had posed “no objections” to the transactions.

“We did not agree because that’s not within our authority as observers,” ASoG’s Dondon Parafina said.

But he also pointed out, “The transactions were not very advantageous to the government.”

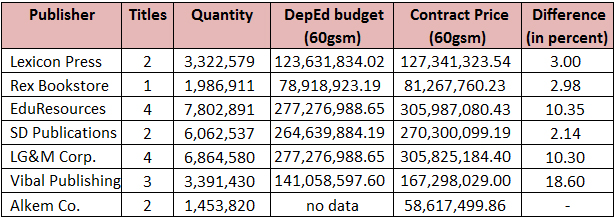

All the contracts, including those awarded in July to EduResources (representing Dane Publishing), LG&M, SD Publications and Vibal Publishing, exceeded the approved budgets for contract (ABCs) or agency estimates for the books. The estimates were based on historical costs and factored in mark-ups.

In a competitive bidding, all the quotations would have been rejected because of this. But direct contracting allows the procuring agency to buy at prices exceeding the ABC after it has negotiated what it deems as the best prices.

“I would say this unequivocally: We believe these are good prices. Where can you get a book for P35?” Varela said.

The prices range from P26.80 to P49.42 per copy except for a 400-page book that costs P75.80.

But Alvia said, “How do we really know if the prices obtained through direct contracting are the most advantageous? How much lower could the prices have gone if competitive bidding were used?”

Said Carole Belisario of Procurement Watch: “Public bidding will result in better outcomes.”

Varela said, however, “You quibble about P1 or P2 per copy for copies that would hopefully be used for three to five years, but in our meetings, Bro. Armin (Luistro) will always tell us, ‘We can debate this to death. But at the end of the day, you must factor into the decision- making the question, How do you quantify the lost months of learning of students?’ That’s very expensive.”

He also suggested that the NGOs scrutinize the purchases in recent years of instructional materials by the DepEd’s regional and division offices at apparently inflated prices. It was partly because of this that Luisitro and his team decided to recentralize textbook procurement, he said.

An analysis of the P1.317 billion worth of transactions shows the difference between the DepEd estimates and the quotes of Alkem, Lexicon and Rex falls between P1 and P3 per copy, and the contracts they bagged exceeding the department’s budget by less than 5 percent. The DepEd paid the three firms a total P267.23 million or, according to Parafina’s computation, about P10 million more than the ceiling it had set.

Negotiations for the 14 other titles led EduResources and sister companies SD Publications, LG&M and Vibal to lower their quotations by P73.8 million, according to DepEd documents. But the contracts, amounting to P1.049 billion, exceeded the DepEd’s P960.2 million, or by P89 million or 9.3 percent. This was partly because LG&M, SD Publications and Vibal Publishing gave unit prices that were P3 to P7.67 more than the agency estimates for many of their titles.

The three sister firms cornered contracts of P743.45 million, which went over the DepEd estimates by P60.4 million. Their representatives had earlier told the BAC that paper costs were high. Another publisher also explained that economies of scale sometimes prevented suppliers from further reducing prices even for huge quantities.

This month, the DepEd will be acquiring the remaining three old titles—Math 1 (owned by Anvil, which has opted to sell only the copyright instead of entering a supply and delivery contract) and Science 4 and 5—for which it has conservatively budgeted P227 million, records show. But it has only P161.7 million left for these, or a shortfall of P65 million.