The Association of Southeast Asian Nations is at the mid-century of its founding, and the Philippines, as chair of the 31st Summit in November this year, is just going through the motion of its chairmanship this week with a ministerial meeting. Late though as it is already, the Philippines nevertheless should seize an opportunity as Chair of ASEAN50 to flag its core interests on national and regional maritime security.

Perhaps, the Duterte government can now take the lead in defining a more appropriate direction on the South China Sea situation to erase the “silence of the lambs” stigma it earned when last April’s 30th ASEAN summit joint statement didn’t mention the concern over China’s activities in the South China Sea where four of the ASEAN members have staked claims over parts of the sea.

The Philippines is the front-line in the Spratlys archipelago dispute situation. Everything it can do to promote joint cooperation/joint development in addressing non-traditional maritime security and ocean governance concerns, whether as confidence-building measures (CBMs) or as provisional measures pending a peaceful settlement of the conflict situation, would surely contribute to alleviating the political tensions in the wider region.

ASEAN Foreign Ministers meeting April 28, 2017, Manila. (Photo from ASEAN50 Secretariat)

Beyond fisheries, the following areas of regional and global non-traditional maritime security interests initially centered in the South China Sea are:

- Sustainability, conservation and protection of the renewable marine resources in the South China Sea to secure the appropriate benefits to the regional States;

- Establishing maritime peace, security and good order for all legal activities, in particular those for global and regional sea trade through the waters of the South China Sea;

- Joint and cooperative scientific research and policy formulation for the national and collective interests of the Indo-Pacific region;

- Discourse leading towards an appropriate regional Agreement for the management, exploration and harvesting of renewable and non-renewable resources in the seabed areas of the South China Sea as a Central Indo-Pacific as a regional common heritage of mankind.

The Philippines is also confronted with serious governance concerns in its eastern maritime frontier of a different sort. Along this entire length of the country’s eastern flank are two marine geological features still largely unexplored and unattended to by the Philippines, but deserving of its utmost curiosity and interest to marine science and in regard to management and conservation of marine resources and biodiversity:

(1) the Benham Rise, and (2) the Philippine Deep; and the adjacent sea bed area that borders International Sea Bed Authority (ISBA) jurisdiction. These two large marine ecosystems/ecoregions would have to commonly contend with exploration and exploitation of resources in the ISBA with accompanying pollution threats to the marine environment and biodiversity.

Powerful lights reveal the true colors of branching corals in Benham Rise. (Photo by Oceana/UPLB)

Monitoring such activities including maritime security monitoring and surveillance in the entire length of the country’s Pacific Ocean frontier, which is over a thousand nautical miles from north to south, would be a tremendous challenge. Collaboration must be established with the ISBA in the northwestern flank of the country starting with Benham Rise and southward the entire length of the Philippine Deep; and with Indonesia and Palau in its southern end.

The seas of maritime Asia is unique in the world because of characteristic regional features that hosts among the most sensitive marine environment and biodiversity, and resources.

They are extremely vulnerable to environmental degradation arising from wanton/ unregulated exploitation of resources, pollution from land-based sources, and human activities such as shipping.

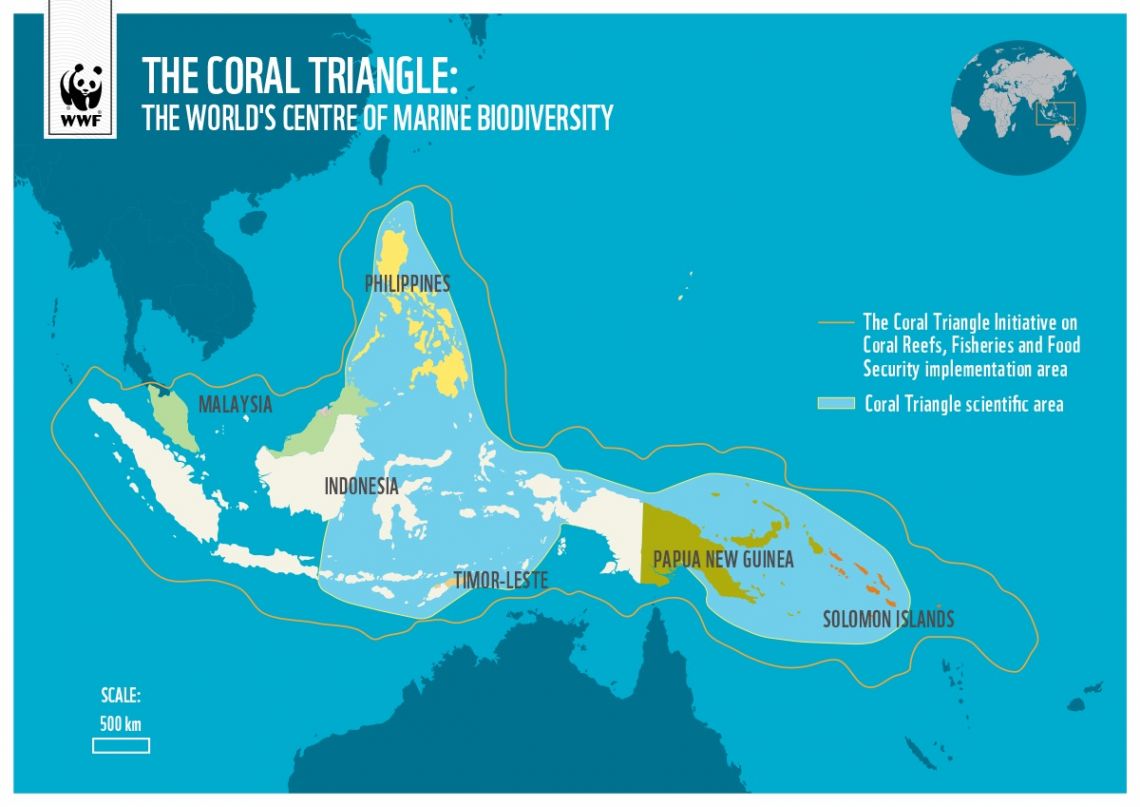

The seas of ASEAN and the Central Indo-Pacific is a tapestry of marine ecosystems that include the Coral Triangle, and with abundant marine and seabed resources that requires continuous monitoring and adaptive protective measures. It is necessary to develop or adapt a regional ocean governance scheme appropriate to the specific/peculiar requirements of the maritime region that comprises the seas of ASEAN and the Central Indo-Pacific.

The Coral Triangle. (Courtesy of Word Wide Fund for Nature)

Ocean governance and maritime security is a collective regional core interest for the ASEAN region and East Asia, burdened with more than half of the world’s maritime trade and shipping volume quantified at US$5.3 Trillion annually. Ocean governance is also essential in establishing maritime connectivity. And the Philippines is the strategic regional epicenter in all aspects of ocean governance and maritime security, whether traditional or non-traditional concerns and issues; and in the thick of maritime disputes that can be a drag on regional integration and consolidation.

On account of the importance of maritime connectivity and ocean governance to AEC-2015 economic/political integration and consolidation, the ASEAN must assume its role as the “central and foremost facilitator and driver of regional economic integration in East Asia” addressing maritime connectivity through ocean governance and maritime security.

A specific and flagship economic/socio-cultural undertaking under the ASEAN 2025 initiative that the Philippines can pursue would be Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM), which would benefit the coastal regions of maritime Asia in regard to food security and disaster mitigation, including Climate Change.

There are already ongoing ocean-related cooperation between ASEAN and aforementioned countries whether bilaterally or under ASEAN auspices. China with its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) regional maritime infrastructure project would be additionally obliged to actively participate in regional ocean governance as a duty and responsibility. The EU and ASEAN has an ongoing ASEAN-EU High-Level Dialogue on Maritime Cooperation. The Philippines must stake a leadership role in these ocean governance endeavors that can already be projected to the aborning UN-sponsored Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdictions (BBNJ) Agreement.

The Philippines must seize the moment. The 2017 hosting of the ASEAN Summit would be the best, and possibly the only, opportunity for the Philippines to stake and define for itself a leadership role in constructing regional ocean governance and maritime security. Borrowing some famous words, the same classic question must have motivated and played in the minds of the authors of the archipelagic State led by Senator Arturo M. Tolentino, thus: “If not us, who? If not now, when?”

(Alberto A. Encomienda was a career ambassador and served as Secretary General of the Maritime and Ocean Affairs Center of the Department of Foreign Affairs until he retired in 2009. He is now the executive director of the Center for Archipelagic and Regional Seas Law and Policy Studies, the “think tank” of balikBalangay. a non-stock, non-profit conservation organization in the Philippines focusing on the marine environment and resources, and oceans law and policy.)