By NORMAN SISON

“GO to Manila, go around the Nips, bounce off the Nips — but go to Manila.”

It was January 1945. General Douglas MacArthur had landed his forces at Lingayen Gulf early that month to begin his campaign to liberate the main Philippine island of Luzon. With his eye fixed on Manila, MacArthur ordered Major General Verne Mudge, commander of the 1st Cavalry Division, to proceed to the capital with utmost speed.

Two other US army divisions competed for the honor of reaching Manila first. It was a virtual tank race.

On February 3, the 1st Cavalry’s Sherman tanks smashed through the gate of the University of Santo Tomas and freed 4,000 mostly American civilians interned there by the Japanese army since 1942. Jubilant Filipinos, who waited for MacArthur to fulfil his famous “I shall return” pledge, spilled into the streets to welcome the American troops.

It was a time for celebration. MacArthur announced on February 6: “Manila has fallen.” But the Battle of Manila was just beginning. When it ended on March 3, what was once the “Pearl of the Orient” became the second most devastated city in World War II after Warsaw — with 100,000 civilians dead.

A number of commemorations are in line this month to mark the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Manila. However, thoughts about the death and destruction weighed so heavily that participants at a recent Ayala Museum forum seemed to have forgotten that the battle also ended three years of Japanese military occupation.

In many ways, Manila never really recovered from its 1945 martyrdom. Much of the Philippines’ historical and cultural treasures were reduced to ash and rubble. Their loss is mourned by today’s generation of Filipino historians and cultural aficionados.

At Ayala Museum, a police officer’s helmet is on display at a newly opened exhibit commemorating the Battle of Manila. Outlandish by today’s fashion standards, the helmet reminds visitors of the old-world charm that Manila was once known for.

At Ayala Museum, a police officer’s helmet is on display at a newly opened exhibit commemorating the Battle of Manila. Outlandish by today’s fashion standards, the helmet reminds visitors of the old-world charm that Manila was once known for.

Inexplicably, the destruction of the city is one issue that has hounded MacArthur to this day because of his decision to allow US forces to blast the Japanese defenders with artillery.

James Zobel, an archivist at the MacArthur Memorial in Norfolk, Virginia, says people today need to understand the conditions on the battlefield. MacArthur had turned down requests from his field commander, General Walter Krueger, to use aircraft because bombs were too indiscriminate. For the same reason, he initially banned artillery.

However, the Japanese were so well dug in that buildings had to be taken street by street, block by block, building by building, floor by floor and room by room. Ricardo Jose, history professor at the University of the Philippines, says the Japanese dug tunnels connecting several main fortified buildings to enable them to reinforce areas under attack — and the Japanese had stockpiled supplies to last them three to six months.

“The Japanese managed to keep the strongest defenses, including the tunnel system, secret. And thus the Americans would only find out how heavily fortified the buildings were after trying to attack them,” says Jose.

The Japanese strategy was to delay the American advance and inflict as many casualties as possible to give the homeland enough time to prepare for an eventual US invasion. The objective: make the fighting so bloody that the Americans would think twice about invading Japan.

When the US body count began to rise and his commanders pressed for the use of artillery, MacArthur reluctantly lifted the ban.

But even with artillery, rooting out the Japanese was exasperating. On Isla de Provisor, an island in the Pasig River, near Ayala Bridge, US troops pumped in over a thousand shells into a heavily fortified building.

“You’d think that would take out anything that’s inside,” says Zobel. “But when Company E of the 129th Regiment went in, they got hammered by the Japanese because the artillery had no effect on them. They were in basements and sandbagged bunkers inside the building.”

Also, US troops had no choice but to move fast because the Japanese were massacring thousands of civilians as they vented their fury on the population. “I don’t see how it could’ve gone differently. If you had let the Japanese stay here, they were going to kill everyone in the city. They were gunning everyone down in the streets,” says Zobel.

Military historians today look at the Battle of Manila as a case study in urban warfare, says Jose, who has, however, found the scholarly scrutiny too cold at times.

“The way some of the military analyses are written, it seems the battle was simply fought by combatants — as if there were no civilians. I find it sad, maybe even criminal, not to mention those who died in the midst of the fighting,” rues Jose.

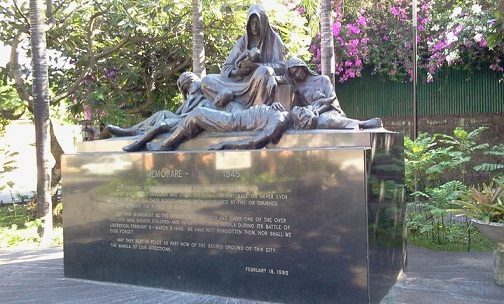

Today, a black marble memorial resembling a tomb at the Plaza de Santa Isabel in Intramuros — the epicenter of the holocaust — stands as a silent reminder.

“This memorial is dedicated to all those innocent victims of war, many of whom went nameless and unknown to a common grave, or even never knew a grave at all, their bodies having been consumed by fire or crushed to dust beneath the rubble of ruins,” read the inscription.

“We have not forgotten them, nor shall we ever forget. May they rest in peace as part now of the sacred ground of this city: the Manila of our affections.”