By ELIZABETH LOLARGA

TO deeply know Myrna H. Francia is to love her like God to whom she gave a feminine and compassionate face and Jesus Christ who she considered her bridegroom.

TO deeply know Myrna H. Francia is to love her like God to whom she gave a feminine and compassionate face and Jesus Christ who she considered her bridegroom.

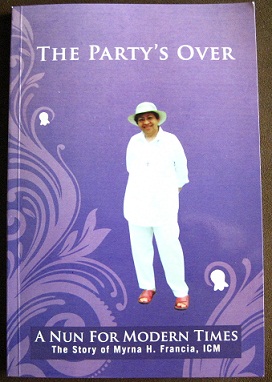

One emerges from the book The Party’s Over: A Nun for Modern Times quite humbled by how she chose to carry out her vocation or her “thirst for perfect love” while not losing her essential pluck and spirited nature.

She was, her brother Joseph writes, “a normal party-going woman who worked in the corporate world and was wooed by suitors before she decided to join the religious life.”

She didn’t live in prayerful isolation from the world. Surprising friends and family, who knew her as not as a santa-santita but a fun-loving girl who wasn’t above doing a mischief or two, she “disturbed the peace of martial law, joining picket lines and protest marches in the company of sweaty laborers.”

A true-life Sister Stella L, the activist nun Vilma Santos played in a Mike de Leon film, Sister Myrna was a more multi-faceted person because long before feminism or feminist theology was talked about, she was living it, even taking on what should have been a parish priest’s responsibilities at a heavily populated university in Baguio.

She enjoyed doses of Vitamin C (chocolate as consolation), good food and fine wine. She wrote poems (one beautiful stanza: “I saw the flowers dying / for lack of rain / I smiled to see / the tears of my pain become / the reason for their living”), drew and played with colors, openly appreciated and cared for nature, drove with some recklessness a secondhand BMW on Europe’s autobahns and an old Volkswagen on Antipolo’s hills.

Her humor was legend. Asked what she would’ve been had she not entered the ICM congregation, she answered bluntly, “I would be on my fourth husband.” When she underwent a mastectomy after being diagnosed with cancer, she claimed that she was left with “a nipple and a dimple.”

Bro. Karl M. Gaspar remembers Sr. Myrna as a fearless, uncomplaining city girl who was part of a pioneering team of pastoral workers living with farmers and fisherfolk in Mati, Davao Oriental. Their work required them to climb hills or travel by pumpboat to reach communities, all towards the goal of building a people’s church.

She remained thankful for those years in Mati at the height of the Marcos dictatorship when the team was almost detained by the paranoid military. Without that experience, she told her brother Luis, she would’ve ended up “a dried-up prune of a nun.”

This joie de vivre was never lost when she and other sisters lived amid factory workers and their families in Bagong Barrio, Kalookan City, when it still had no concrete roads and sewage and garbage disposal systems. That meant living in a space that was small, hot, had little privacy and where the nuns did everything from cleaning to cooking, washing and marketing.

There Sr. Myrna helped set up a parish labor desk where leaders of factories and unions met to discuss their problems and find ways to resolve them. Gifted with a patient listening ear, she amazed the community, coming across as a close friend, not just a spiritual adviser. She joined them in pickets and marches.

Lydia Lascano, ICM, who was with her, recalls, “You can imagine her anger at the situation of society, where a country claims to be Christian, but it is not Christian at all in the way it is treating its people. That will really drive you to activism.”

Sr. Myrna shared an observation about learning from the poor: “…[M]uch more have I learned from these mayukmok (ordinary people). Through their unsung lives and unheralded deaths, they bring in the ani, or harvest, of justice and peace.”

But this Christ-like compassion for the poor brought disapproval from the ICM hierarchy to the extent that Sr. Myrna and 13 other sisters were, in her words, “ready to break off and start a new branch under the protection of an activist bishop.”

Leovino Ma. Garcia recalls how Sr. Myrna once wept unashamedly in his office because “she felt persecuted. Her superiors, she thought, no longer believed in her loyalty to her congregation because they misunderstood her commitment to the economically poor of our society.”

She stayed on to become part of ICM’s transformation until she rose to the post of district supervisor or the equivalent of provincial superior. There she was able to introduce innovations. Still, she had the clear-sightedness to realize that the EDSA uprising that kicked out Marcos “had not empowered the workers yet.”

(The book is published by the Sister Myrna Francia Memorial Inc. to help fund scholarships for poor, deserving students in “non-elite” schools.)