By KLARIBELLE ANNE LANGUAYAN

AT gunpoint, his police interrogator asked him to recite a poem. Already subjected to torture, poet and peasant activist Axel Pinpin couldn’t think of any as he hadn’t memorized any, so he made up one:

AT gunpoint, his police interrogator asked him to recite a poem. Already subjected to torture, poet and peasant activist Axel Pinpin couldn’t think of any as he hadn’t memorized any, so he made up one:

Ihimlay mo kami sa piling ng mga gahis,

sa ritmo ng awit ng putok ng baril

at sa ngalit ng tugmaan kong matatabil!

Impressed by his verses, his interrogator applauded. But he would also tell Pinpin: “(Marunong ka mang tumula pero titiyakin ko sayo, ito na ang huling pagkakataon na tutula ka (You may be a poet, but I assure you this will be your last performance).” Pinpin thought he surely was going to die.

Pinpin got to live. In August 2008, 28 months after he, two other members of the peasant organization Kilusang Magbubukid ng Pilipinas, their driver and his friend—collectively called the “Tagaytay 5—were abducted in Tagaytay and detained, they were freed on orders of a local court that junked the rebellion and illegal possession of firearms charges against them.

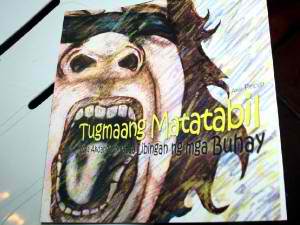

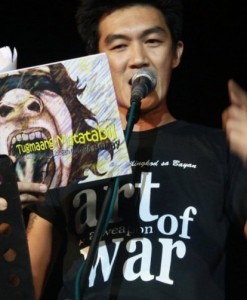

The poem, titled “Unang Gabi ng Interogasyon (First Night of Interrogation),” would be included in his book of poems “Tugmaang Matatabil” that was launched months after he was released. Almost three years later, plans are afoot to release the second volume of Tugmaang Matatabil which would include other poems made during his detention.

Lumikha, lumikha at lumikha nang maingat,

nararapat na may mahika ang salita.

Poetry apparently runs in Pinpin’s family. As young as 4 years old, he regularly recited a two-line poem penned by his father in front of relatives. In grade school, he would perform for winners of beauty contests in his hometown in Indang, Cavite. Influenced by the punk culture in high school, his poems started to develop character. His first inspiration (besides his father, he joked) was Jun Cruz Reyes, after reading his poem in the compilation Mga Agos ng Disyerto.

An agriculturist by profession, Pinpin studied horticulture at the Don Severino Agricultural College (now Cavite State University) in Indang. He submitted articles to the student publication, only to get rejected. This led him and his colleagues to put out a guerrilla publication.

He later became a contributor of the Kilometer 64 poetry collective and a fellow of the 35th University of the Philippines National Writer’s Workshop.

Planado at tiyak nang simulan nilang hukayin

ang libingan nilang magiging mga martir.

By his own account, Pinpin was a “late-bloomer” activist.

By his own account, Pinpin was a “late-bloomer” activist.

When he was 24, while working at the Department of Science and Technology as an agriculturist, he became affiliated with AGHAM-Advocates of Science and Technology for the People. He would later find himself drawn to the Kalipunan ng Magsasaka sa Kabite (Farmers’ Confederation in Cavite), the KMP’s chapter in Cavite, where he worked as researcher and public information officer.

On the afternoon of April 28, 2006, the Tagaytay 5 that included Pinpin were on their way home from giving paralegal training and inviting peasants to the May 1 mobilization when a white van cut their car on Talisay’s zigzag road. Soldiers jumped off the van when they heard the command: “Hinto! Baba (Stop! Get off)!”

Pinpin was seated behind the driver’s seat. The next thing he knew, a gun was pointed at him. He exclaimed, “’O teka san nyo ko dadalhin? Anong problema (Where will you bring us? What’s the problem)?”

The peasant activist was shoved to the ground by one of the armed men. He glanced back and saw about 30 to 40 gun-wielding men behind their vehicle. The roads were blocked, and there was nowhere to run because they were on a cliff. The Tagaytay 5 were then handcuffed, blindfolded and pushed into the van.

At their detention cell, they were tortured and forced to admit that they were members of the communist New People’s Army. For almost a week they were held incommunicado.

For Pinpin, their abduction and detention all formed part of Oplan Bantay Laya launched in 2001 by then President Gloria Arroyo. Arroyo’s war on terrorism was to eliminate all antigovernment or so-called “terrorist” forces by 2006.

Subali’t ang nagsusulat ng tula ay di panaginip,

gumigising ang makata sa katauhang nakapiit,

nag-aalumpihit

Detention of 28 months didn’t stop Pinpin from writing. “Tugmaang Matatabil” contains 53 poems about peasants’ life, prison days and his life perspectives. Everything from his “memory bank,” as he calls it, poured out.

“Tugmaang Matatabi” would be Pinpin’s second book. But while his first one, “Tugmaang Walang Tugma”, released in 1996 was critiqued as “anarcho-romantic,” “Tugmaang Matatabil” displayed a sharpened outlook in life and struggle for change.

Malapit na kami! Ilang hakbang na lamang!

Maghanda’t maniningil tayo ng pautang!

Pinpin had originally thought of taking to the mountains upon his release, feeling this was the most logical and justifiable form of struggle in this kind of system. But he later changed his mind and opted to advocate his cause in the open.

Now 39, with two children, he remains a committed activist and passionate peasant advocate as secretary general of the peasant alliance Katipunan ng Samahang Magbubukid sa Timog Katagalugan (Kasama-TK).

The upcoming release of second volume of Tugmaang Matatabil and a collection of short stories certainly excites Pinpin. But he, too, knows the better venue for his poetry: “It would be more worthy to recite an unpublished poem in front of thousands of people in a rally than to have a book on display that will never be bought yet alone read.”

(The writer is a journalism student at the University of the Philippines-Diliman who submitted a version of this story to her Journ 101 class under VERA Files trustee Yvonne T. Chua.)