By ELIZABETH LOLARGA

FAR from being “a chromosome accident,” a child with Down syndrome is not Nature’s mistake. And it is likewise futile for a parent to wallow in guilt and endless self-blame or ask “What did I do wrong?”

Malu Tiongson-Ortiz, author of Embracing God’s Purpose for My Special Child (OMF Literature Inc.) drew heavily from her faith when she argued that “the Lord is perfect and never makes mistakes. He created our children to be out of the ordinary, and designed each one the way he or she is for His own purpose. We are the parents He chose for these children, and each child was made according to His plan. If our children are called special, then doesn’t that make us special parents? Definitely! I feel unique, because my daughter herself is unique.”

She discovered how Down syndrome endowed her child Clarissa Lorraine with a genuine and pure heart. Like other children with this condition, once labeled Mongoloids, Clarissa understands “right and wrong, humility, simplicity, contentment, forgiveness, giving, and have a joy and peace that many people do not have.”

In the beginning, the author went through a period of denial when the pediatrician broke the news to her about the certainty that her daughter had Down syndrome (named after English physician John Langdon Down who described its features and considered it “a congenital disease caused by chromosomal abnormality”).

When she was told that the baby had the features (slanted eyes, round face, small nose with low nasal bridge, deformed ears, straight palm crease), Ortiz adamantly answered back that the daughter looked that way because she was Filipino-Chinese with siblings who had round faces and low nasal bridges like other Pinoys.

The revelation couldn’t have come at a worse time because she was then going through a marital crisis and had fled the family abode. Inevitably, she thought that her pregnancy was doubly and emotionally stressful or Clarissa “was conceived out of distress” (in Filipino, pinaglihi sa sama ng loob). She couldn’t bring herself to break the news to her family and friends, and admitted that pride got in the way.

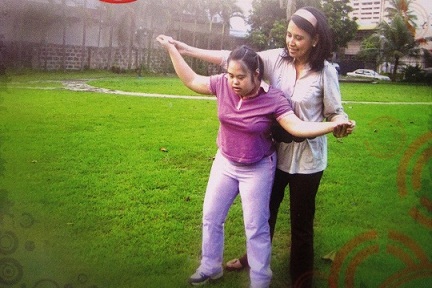

A few weeks later, she accepted that Clarissa was a most-awaited daughter and braced herself to make a difference in the child’s life. Ortiz studied what the syndrome was all about, dispelled its myths, found support groups (Praying Wife Ministry and Down Syndrome Association of the Philippines) and went to the extent of home-schooling Clarissa, teaching her to pray and to find artistic expression.

Ortiz has prepared for any eventuality, giving an example of a last will and testament that specifies who is authorized to be legal guardian in the event of a parent’s death.

For the Down syndrome child who can’t afford to support himself financially, she suggested that “it is the responsibility of every parent who is able to set aside funds for this purpose to build up a substantial amount in time deposit for their special child, so as not to burden his siblings or relatives.” Another way is through an insurance policy where the special child is the sole beneficiary. These funds would take care of physical needs and medical bills.

For the Down syndrome child who can’t afford to support himself financially, she suggested that “it is the responsibility of every parent who is able to set aside funds for this purpose to build up a substantial amount in time deposit for their special child, so as not to burden his siblings or relatives.” Another way is through an insurance policy where the special child is the sole beneficiary. These funds would take care of physical needs and medical bills.

In some Oriental societies, a handicapped child is seen as a bringer of good fortune, not as, in Ortiz’s belief, a part of God’s design to teach families to seek and pray to Him, to heal a broken relationship, to increase faith, to mold character, to value life. When Clarissa’s father Claro was told that the child, whose condition was aggravated by deafness, muteness, uneven legs and bipolar disorder, would bring them luck, he exclaimed, “What do you think of our child, a rabbit’s foot?”

This is not just the story of one family but also of several others like laundrywoman Linda who thought that Down syndrome kids were only born to rich people and who let her special son Jericho get soaked in rain. She thought this would hasten his death because she couldn’t afford to pay for his hospitalization and medication. Ortiz testified about her own experience with Clarissa and persuaded Linda to be part of the DSAP’s early intervention program. Jericho survived and remains healthy.

Another case is that of Elizabeth, a former prostitute, and son Ezel, her joblessness because she was his primary caregiver, their eviction from their room until chance found her at a Down Syndrome Consciousness Week event. She met Ortiz, and her life took a turn for the better. Elizabeth rebuked prostitution once and for all and found work as a manicurist.

Ortiz quoted French geneticist Jerome Lejeune on how to handle a special child: “Look at the child as a child first and at the disability second. Love that child unconditionally and that child will bloom”