(Photos sourced from Carlos Celdran)

By MATTHEW REYSIO-CRUZ

THE whole nation wondered who he was.

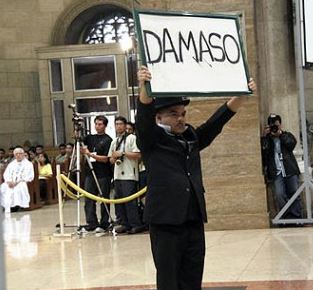

Sporting a black overcoat and top hat, performer and tourist guide Carlos Celdran stood before a group of bishops at the Manila Cathedral in September 2010 holding up a sign with one simple, familiar word: Damaso. It was a reference to the power-abusive friar in national hero Jose Rizal’s 1887 novel Noli Me Tángere.

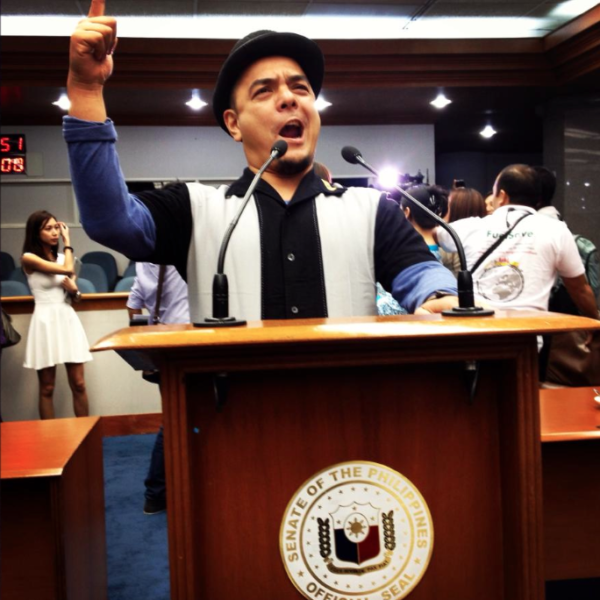

Celdran shouted “Stop getting involved in politics!” before being taken away by police.

That same night, the Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines filed charges against him for violating Article 133 of the Revised Penal Code, which forbids “offending religious feelings.” Last January he was found guilty of the crime by the Metropolitan Trial Court in Manila. Now free on bail, he awaits the possibility of being sentenced to up to 13 months in prison.

All this was in the name of the then Reproductive Health Bill, a measure that would give government funding for contraception and which was heavily opposed by the Catholic Church.

Celdran says he was motivated to fight for the bill because of what he saw whenever he conducted his popular walking tours around Manila. Alongside the beautiful buildings and grand remnants of Philippine history, he says, was a picture of harsh poverty, painted by “street children” and “sick, unwed mothers.”

“There’s no way I could put a smiley face on it, especially when talking to tourists,” he says. “And I realized the real way to alleviate poverty is by empowering the Filipino family. You empower one Filipino woman, and you empower an entire generation.”

His unique form of protest made headlines and plunged him into the public eye overnight. Supporters commended his boldness. Critics called it audacity.

But to those who know him, the 40-year-old Celdran was simply pushing boundaries—something he’s done all his life. He had landed a job making political cartoons at Business Day during the martial law era when he was just 14. When he was in high school, he became the youngest member of the Samahang Kartunista ng Pilipinas.

To him, though, he was just using what he knew: Activism in art.

“I believe that arts and culture can really change society. And I think by just using cosplay, and using the references of our history, it resonated with Filipinos,” he says. “Imagine if I went there in jeans and a T-shirt instead, or held up a sign that said ‘Pass the RH Bill’ and not ‘Damaso.’ With one word and with one image, 89 million Filipinos knew exactly what I was talking about.”

The move added “cultural activist” to Celdran’s growing list of titles, which include former production assistant, dancer and family planning advocate.

But Celdran is first and foremost an artist.

After being enrolled for almost two years in the University of the Philippines’ Visual Communications Department, he transferred to the Rhode Island School of Design. There he graduated with a degree in Performance Art, after shifting out of Painting when he realized that he was allergic to paint. In 1996 he won the Yvonne Force Art Award, which gave him enough money to move to New York City.

While there he worked through a variety of jobs, his first being a cheese counter boy at Dean & DeLuca. After being caught eating the cheese, he was moved to the fish station. He then began to bring soy sauce to work so he could eat the fish raw.

The last straw came when he picked signing the lease for his apartment over going to work on time.

“I knew as I was signing it that I was fired,” he laughs. “And so I decided to take a slow walk from the office to work. I smelled the roses. I ate an ice cream. I looked at the park. By the time I got to work two hours later the boss says, ‘You know you’re fired, right?’”

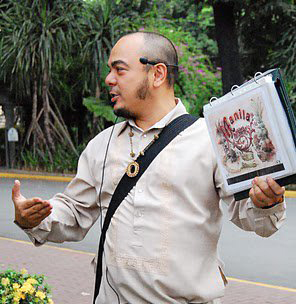

He would eventually find the perfect job years later back in the Philippines, in the form of Walk This Way, a touring company he founded in 2002. Celdran, not your average tour guide, gives customers a true walk to remember.

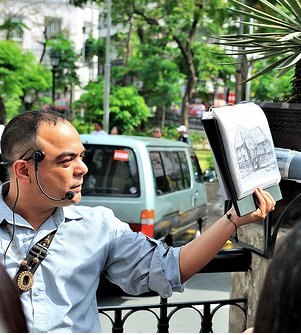

He dons period costumes. He dances. He sings. He has his own visuals. He narrates scenes and reenacts situations.

“It’s not like I wanted to become a tour guide,” he quips. “I wanted to become a performance artist. Tour guiding was just my vehicle to become that.”

Performing is exactly what he does, in both “If These Walls Could Talk,” a tour of the walled city of Intramuros, and “Living la Vida Imelda,” a tour of the Cultural Center of the Philippines integrated with the life of former First Lady Imelda Marcos. He walks his audience through the chapters of Philippine history, breathing new life into buildings and figures that have been around for centuries.

“The tour in itself for me is the inspiration. I look at my tour as like a practice. I don’t look at it as a job,” he reflects. He relates his doing the tours to how people do yoga or cross-fit. To him, the tour is religious experience.

“I’ve been doing it every day for the last 10 years, so I have the blessing of having each performance, each day, as a dress rehearsal. And even today I’ll probably try something new, and tomorrow I’ll try something new,” he says.

The environment he grew up in however was poles apart from Downtown Manila where he currently resides. He lived in Dasmariñas Village, a gated community in the bustling city of Makati.

“And I hated every minute of it,” he says. “It was the most boring place in the world. My world was between Dasmariñas Avenue and San Agustin, which makes my world pretty much one kilometer wide.”

High school, especially his work at Business Day, gave him his first exposure to the Manila that he would come to fall madly in love with.

“There were no walls. There were no security guards. There were no upper middle class lives of desperation,” he recalls. “Everything just seemed so liberating and colorful.”

The tours are also motivated by Celdran’s desire to change the way locals see Manila as a “dirty, dangerous, threatening place.” A city is whatever you want it to be, he believes.

He says wholeheartedly, “I want Filipinos to change that perception and be prouder of their older districts in Manila. Just because it’s old, does not mean it needs to be thrown away. In this aged part of Manila lies our history.”

(The writer is a journalism student at the University of the Philippines-Diliman who submitted this story to his Journ 101 class under VERA Files trustee Yvonne T. Chua.)