By Elizabeth Lolarga

HOW many times has it been said that not only is motherhood thankless but it is the most difficult job description in the world? There are many mothers out there close to giving up but continue to do what has to be done: raise children who they wish deeply in their hearts will grow to be smart, creative, kind and confident adults so they “have things to offer the world.”

HOW many times has it been said that not only is motherhood thankless but it is the most difficult job description in the world? There are many mothers out there close to giving up but continue to do what has to be done: raise children who they wish deeply in their hearts will grow to be smart, creative, kind and confident adults so they “have things to offer the world.”

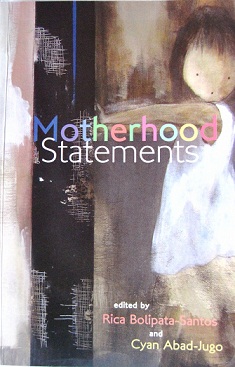

Noelle Q. de Jesus, one of the contributors to the anthology Motherhood Statements (Rica Bolipata-Santos and Cyan Abad-Jugo, eds., Anvil Publishing), remains in the thick of parenting children while holding down a job at a time when being a full-time homemaker, the way her grandmother was, seems quaint and of another era.

Despite a hot temper and undergoing earlier difficulties of seeing a daughter born with a cleft palate and watching her survive complex surgeries, she is “saved by magical days” that enable her to be “thankful I have been allowed to be their mother, such as I am. I pray every day that I get better at it.”

There are also essays from the point of view of a daughter assessing the mother through unfiltered lenses. The older woman is perceived as the mortal enemy. Abad-Jugo is no exemption. She points to a mother who “had given me a miserable childhood.” She recalled being at the receiving end of barbed retorts (“e.g., Me: I am going to take Fine Arts in UP. She: May talent ka ba? Me: Why have you allowed Cybele to go on girl scouting trips, when you have never allowed me? She: Because she isn’t as tanga as you.”).

It is when the author becomes a mother herself that forgiveness of “the enemy” and knowledge of where the family elder was coming from set in. Even Gilda Cordero-Fernando had mother issues, declaring at the start that “my mother was the bad guy in my life…Like most contrary children, I vowed to be better than she.” Only to discover that when she becomes a mom, her own kids have expectations of what they wanted her to be so “you never get the right mother!”

Ajie Alvarez-Taduran summoned courage to write about her mother. When her mother died, she refused “to look at my mother in death. I want to remember her exactly the way she was: cold, insensitive, hot-tempered.” In the end, she forgives herself and her mother, describing the umbilical cord’s path as stretching “between the world of the living and of the dead, but it is more secure than ever.”

With difficult mothers, in Luchie Maranan’s words, “it takes a generation”, in her case, her own daughters, for the family matriarch to be fully appreciated

As her mother is consumed by Alzheimer’s Disease, Mari Jina Andaya misses the termagant who was her alarm clock. Andaya had gotten used to waking up to the highest decibels of: “Jina! Gumising ka na para makakain ka bago ka umalis ang bagal bagal mong kumilos mamaya magkakape ka lang tapos aasim na naman ang sikmura mo lagi ka na lang ganyan kape nang kape walang laman ang tiyan mo mabubutas na yan tapos papalitan yan ng goma!”

Her essay is followed by FH Batacan’s moving “To a Friend Who Is Losing Her Mother” on the ravages of Alzheimer’s when a beloved becomes a stranger. Her pointers: “Tell her that you are starting to look more and more like her every day. And that you like it…Tell her you can pick out the freshest fish, the sweetest fruit, the best vegetables at the wet market because she taught you all these things when you were a child.”

Batacan urges the reader to “tell her. Sometimes, many times, the proof of a life is in the little things, the everyday things. The things we don’t remember until someone reminds us, the things we don’t notice until they are no longer there.”

Bolipata-Santos’s “For Teodoro” and Honeylein C. de Peralta’s “When My Daughter Was Born” speak of coping with and loving children with special needs. After going through stages of grief till she reached acceptance, de Peralta writes that mothering her Rocio “is a grand adventure, one I would not exchange for anything in the world. And every day…I am amazed that my daughter is as beautiful and precious as she is.”

The male writers seem to have an easier, funnier handle on their mothers: Chalson Ong fondly calls his “the panda mother” while Ian Rosales Casocot learned strength and perseverance from a Southern belle of a mom who still wears high heels at 78 and finds the current James Bond “squat ugly.”

The 30 contributors to this book testify how life with mother can truly be filled with serio-comic moments.