By ELLEN T. TORDESILLAS

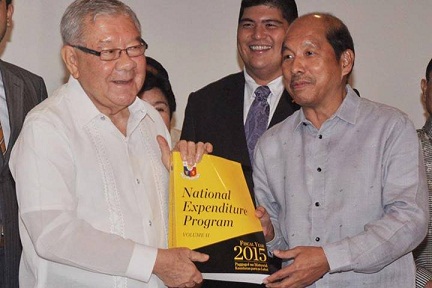

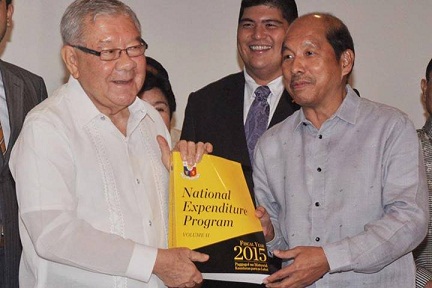

THE P2.6 trillion 2015 budget submitted by Malacanang to Congress will institutionalize the practices in the Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP) which the Supreme Court had declared unconstitutional.

In the 2015 budget proposal, “savings” is now defined as portions of allocations that “have not been released or obligated” due to “discontinuance or abandonment of a program, activity or project for justifiable causes, at any time during the validity of the appropriations.”

With this definition, President Aquino and Budget Secretary Florencio Abad can hijack funds allocated to projects under the 2015 General Appropriations Act as what they did with DAP the past three years.

The new definition of “savings” differed from what was in the 2011, 2012 and 2013 GAA which referred to funds that are “still available after the completion, or final discontinuance, or abandonment of the work, activity or purpose for which the appropriation is authorized.”

Both chambers of Congress are dominated by Aquino’s allies so it’s expected that the new definition of savings would be adopted. Aquino and Abad can then juggle the funds just like they did with DAP and not fear of being charged with violation of the law.

Malacañang’s new definition of savings undermines the power of Congress over the purse as stated in the Constitution and perverts the system of checks and balance which is the essence of democracy.

The Center for National Budget, a private organization dedicated to empowering Filipinos with knowledge of the budget said “The DAP perpetuates a dysfunctional, illegal and unconstitutional budget practices and mechanisms, allows the concentration of extraordinary powers to a few individuals way beyond that the Constitution contemplates and stipulates.”

“Disallowing the DAP is a step forward for transparency and accountability,” the CNB further said.

Malacañang’s claim of transparency and accountability has been rendered hollow by this attempt to legalize and passing on as beneficial what has been exposed as a sinister practice.

Lawyer Joel Butuyan of Roque and Butuyan Law Office sees danger in the institutionalization of DAP practice.

In his Facebook post, Butuyan said, ““My beef with the Aquino administration’s attempt to institutionalize the DAP is that it represents a shortsighted view of what’s good for the country. The DAP gives the President enormous discretion in spending the people’s money. By wanting the Supreme Court to engrave in stone this Presidential discretionary power, the Aquino administration any president — good, bad, evil, witch, gremlin, e.t., mangkukulam, kapre, maligno — now and forevermore wants any to enjoy this power. To plagiarize Conrad De Quiroz, there lies the rub.

“The Aquino administration is only myopically looking at what glorious good it can do during its two remaining years in office, if allowed unfettered use of DAP powers. It is not thinking what horrendous damage it can do to the country under subsequent Presidents with black achy breaky hearts.”

Rep. Neri Colmenares of the Bayan Muna partylist group said if Malacañang’s new definition of savings is adopted in the General Appropriations Act for 2014, then savings “may be redefined reviewed or adjusted on a yearly basis.”

This will open the floodgates to tampering of the approved budget. That would be supremely ironic for a president who made the fight against corruption his administration’s battle cry.

Butuyan said, “The Aquino administration fails to realize that a lot of the reforms it is doing are character-dependent reforms. Anti-corruption campaign, infrastructure projects, stringent tax and customs collection etc. are all character-dependent reforms. The success and impact of these reforms depend entirely on the character of the sitting President. A kupal and kapalmuks President gets elected to power and he/she can completely reverse course and bring back the cabaret dancing old days of “what are we in power for?”

With constitutional check and- balance compromised, the burden now has to be shouldered by a vigilant public. This is where the Freedom of Information law is crucial.

Butuyan said, ““If the President wants his character-dependent reforms to continue beyond the years and decades of his term, he must arm the people with the power to scrutinize every nook and cranny of governmental action. Allow the glare of public scrutiny to illuminate even the deep recesses of government.”

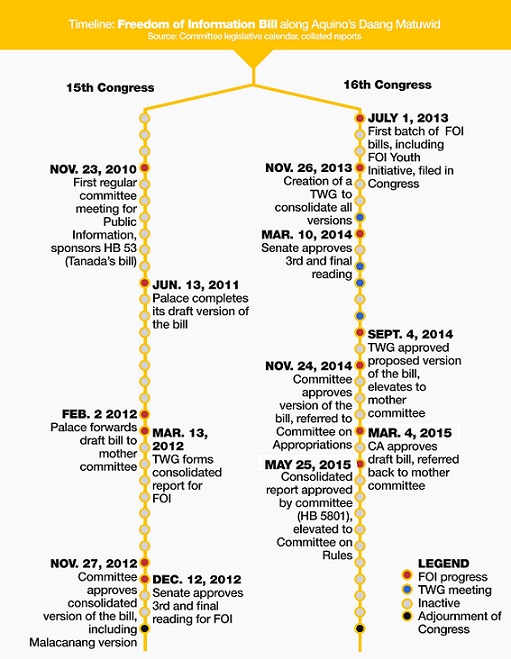

With only two years left of the Aquino presidency, Malacañang finally included in its list of priority measures PNoy’s campaign promise of a Freedom of Information law.

Butuyan said: “If Aquino wants to have a lasting legacy, the passage of the FOI will be the history-defining landmark of his Presidency. The FOI law will have the impact of an EDSA revolution. With the passage of the FOI law, the people will no longer have to necessarily embark on a revolution to make government accountable. The people will only have to avail of the FOI mechanism in order to demand information, demand documents, and make the government accountable for its actions.”

Past experiences tell us that the applause should be held until the President Aquino signs the FOI law. His media bashings betrayed a lack of appreciation of the role of press freedom in good governance and in a vibrant democracy.

Butuyan further said, “ If the President does not work mighty hard for the passage of the FOI law, it is clear that he only wants bragging rights, an ego trip — ‘This is how clean and good I was during my term, and this is how bad we are now” —- and not legacy.

“Move heaven and earth to pass the FOI law, Mr. President. You have to move it, move it . . . . you have to move it, move it . “