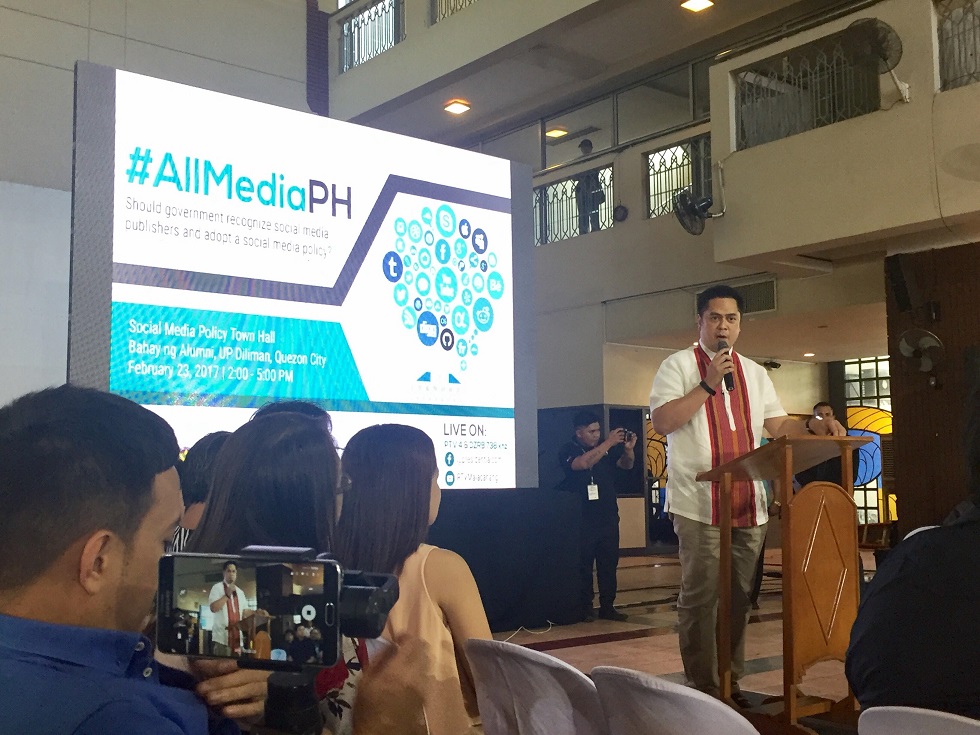

Communications Secretary Martin Andanar delivers his speech

during the three-hour discussion on the Palace’s draft social media policy for

bloggers at the University of the Philippines Diliman.

The newly-crafted social media policy that seeks to grant bloggers access to cover Malacanang events drew mixed reactions from bloggers, lawyers, internet rights advocates and the academe for its implications on Internet freedom.

Released by the Presidential Communications Operations Office (PCOO) during a recent Malacañang-sponsored event at the University of the Philippines (https://www.scribd.com/document/339999377/Draft-PCOO-Memo-on-Social-Media-Policy) the 10-page policy draft provides a system for accreditation of social media users to cover activities of the President.

The policy differentiates between two eligible applicants:

- A “social media publisher” is an identified person or group of persons that maintains a publicly-accessible social media page, blog or website, which generates content and whose principal advocacy is the daily dissemination of original news and/or opinion of interest, with at least 1,000 followers or subscribers, and which has published regularly and consistently for a period of twelve months.

- A “social media user,” meanwhile, refers to a person or group of persons that maintains a social media account, which generates content expressing his/her or their opinions, viewpoints, commentaries, the sharing of news and information, and other similar or related communications activities.

PCOO-accredited social media publishers shall be entitled to faster processing for on-site or access passes to Palace events and inclusion in the PCOO mailing list. Accredited users, meanwhile, will be included in the PCOO participatory social media program “Laging Handa.”

They shall enjoy these benefits in exchange of posting, sharing and disseminating on their online pages PCOO press releases. They shall also validate the truthfulness of the news content they generate, publish and share.

According to Press Secretary Martin Andanar, the crafting the social media policy was spurred by President Rodrigo’s meeting with bloggers and his supporters in January.

In his speech, Andanar acknowledged how blogging has changed the political discourse: “Today, bloggers are very passionate about making their decisions known on certain issues. As a result, they can inspire a following that can go up as high as 400,000 to 4 million.”

Lawyer Jesus Jose Disini is supportive of the policy, saying the initiative only shows that the government is not isolating itself, and that it wants to engage the public in discourse.

“The administration is not just paying lip service towards transparency,” Disini said.

In case others may feel that their rights to free speech are impinged on by the policy, Disini is confident that there are “people who will bring the appropriate complaint.”

“Nobody in government wants to violate the fundamental rights of another. It is against their interest to do that….They might make a mistake once in a while but if they do so, I expect that people in government are wise enough to take corrective action,” he added.

But some bloggers and internet rights advocates have found some provisions and implications worrisome.

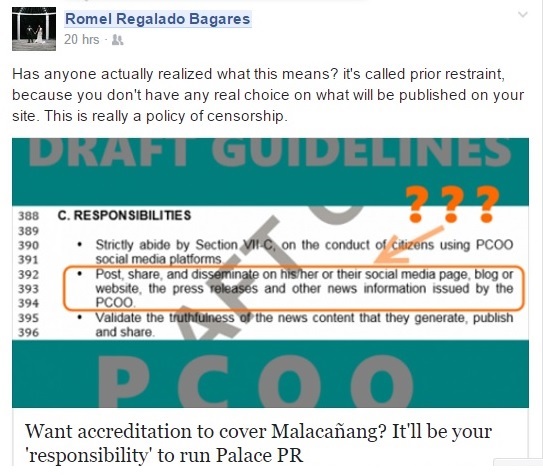

Journalist- turned- lawyer Romel Bagares, warned of the provision which said an accredited social media user in Malacanang is required to “Post, share, disseminate on his/her social media page, blog or website the press releases and other news information issued by PCOO.”

“Has anyone actually realized what this means? It’s called prior restraint, because you don’t have any real choice on what will be published on your site. This is really a policy of censorship,”he said.

Al Alegre of the Foundation for Media Alternatives said he fears that the policy, coincidentally released along with the filing of a bill that regulates social media platforms, might be used as a tool for content regulation.

On Tuesday, House Speaker Pantaleon Alvarez filed House Bill 5021 or the Social Media Regulation Act of 2017. Prompted by the plethora of fake accounts online, the bill seeks to mandate social media platforms to verify the authenticity of its users.

Alegre said he is bothered by the current communication climate which is mired of accusations of bribery, lack of coordination among communication arms of government offices, and lack of condemnation for online threats and harassment.

“Any regulation of online speech is problematic,” Alegre said. “I would like to see in the (social media) policy statement a clear orientation towards freedom of expression — online and offline.”

Meanwhile, blogger Trixie Cruz-Angeles pointed out the requirement on social media following, which is at least 1,000 followers. She said followers and longevity in blogging does not equal reach and credibility.

The same sentiment was echoed by Rey Joseph Nieto, who is behind Thinking Pinoy, in a five-minute recorded video aired during the event.

Cyber lawyer and former journalist Marnie Tonson of the Philippine Internet Freedom Alliance said the main problem with the social media policy is that is actually “two sets of rules mashed together.”

A social media policy is unique to a corporation, a blogger or a government institution, but accreditation is about the news media, he pointed out.

“Social media policy and the rules of media

accreditation shouldn’t be together. How you would accredit social media should

basically be the same way you accredit print and broadcast media,” Tonson said.

Journalism student Thomas Benjamin Roca, meanwhile, fears that the policy may only turn out be an “added accreditation” that would legitimize people who spew out fake news.

There is nothing wrong in giving access to social media users who want to cover Malacanang. “But does Malacanang need to give access to virtually everyone? I don’t think so, because not everyone has the capacity to process and analyze information pertaining to Malacanang.”

He added that the rules do not have anything to do with how accredited bloggers shall comport themselves outside of Malacanang events.

“You could still distort the facts you reported as an accredited Malacanang reporter kapag lumabas ka na, kapag nagsusulat ka na sa site mo,” Roca said.

To deal with this, PCOO Assistant Secretary Kris Ablan suggested that accredited users can still maintain their personal account, and have a different “news account” accredited when covering the president to delineate their personal sphere.

“We recognize they have their own independence and autonomy and they can post whatever they want on their own pages but when they comment or report using PCOO social media platforms…they should abide by common etiquette and decency,” he added.

Ablan said the policy is raw and not yet final. It has not set a limit on the volume of applications for accreditation. The PCOO has yet to convene a stakeholders meeting to consult media to double check their revised policy.

On fears that the policy might be used as a tool to regulate content, Ablan clarified: “Nothing in the policy imposes some kind of regulation. Any person still has the freedom to write anything, it’s a protected constitutional right. It’s just that if you want to cover the president, we have some kind of accreditation para naman magkalinawan tayo (to make things clear.)”