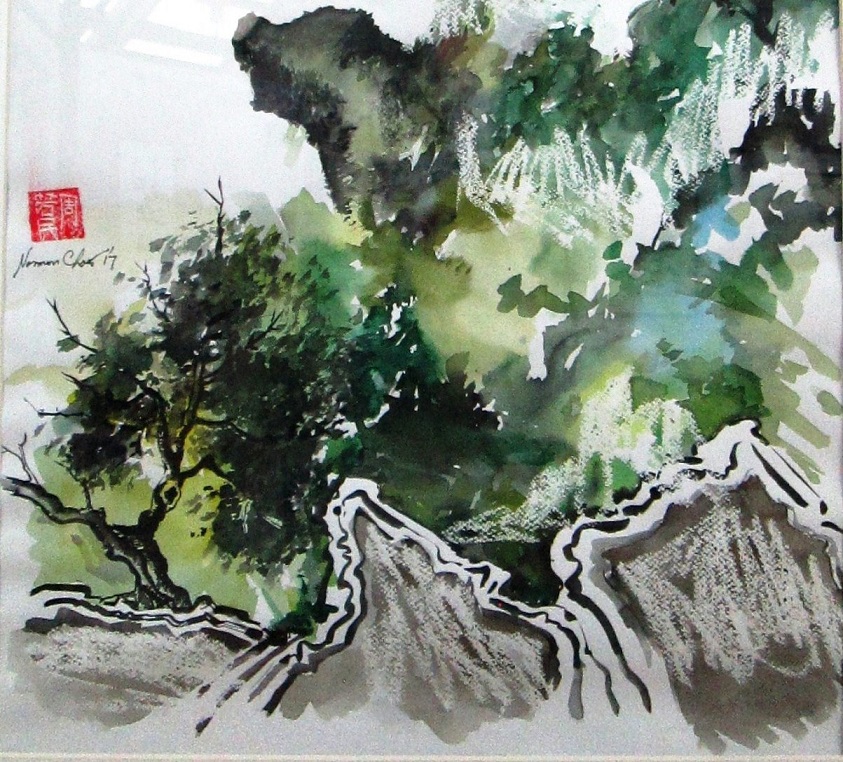

Detail from Mountainscape by Norman Chow

BAGUIO CITY—At the Chinese painting exhibition extolling Baguio’s landscape, father and son Norman and Chino Chow, both born and raised in this city, showed through 15 works what the real skyline of this rapidly urbanizing getaway place is.

“It is not those high-rise buildings,” Chow the Elder emphasized. “The true skyline is the mountain.”

Heads nodded at the opening of “Bi Yao” at the top floor of the Baguio Museum as though the audience, composed mainly of city residents, were one in their nostalgia for the Baguio that was.

Father and son acted as poets of the brush as they rendered with ink and pigments on rice paper the natural terrain of this former American hill station, even including landmarks that are already gone or leveled to the ground to make way for other structures. In this sense, the two are imaginative documentarists and environmentalists trying to save what is salvageable.

Chow the Younger said Barangay Irisan is their common subject because that is where they live. There were many good spots there beyond its notoriety as the garbage dump of the city. His father agreed. “Irisan is the sunset barangay of Baguio. It’s on the western area of the city. That is a good place to watch the sunset.”

The elder Chow, 62, also paints in oil and acrylic and uses dry media (pencils and pastels). A humanities graduate of the Ateneo de Manila University, he was a pioneer of the artists’ group Tahong Bundok. He is mentor to art students like floral painter Toottee Chanco Pacis who lent her greenhouse so father and son could paint undisturbed. Chow influenced another student, the late writer-painter Baboo Mondoñedo, who mounted several consecutive solo shows before her untimely demise. Mondoñedo developed her own style after learning Oriental painting.

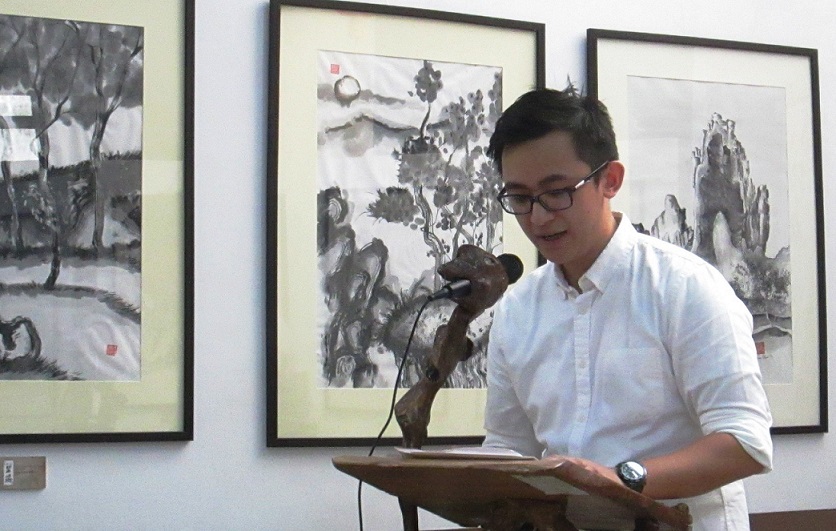

Norman Chow shows off an on the spot work he and son Chino did at the exhibit opening.

Chino, 27, began painting and joining art contests as a child. He is a food blogger, social media influencer and radio jock. He is self-taught in Chinese painting but sometimes draws inspiration from his father’’s work. He has tried his hand in graphic arts and mural painting.

He started doing Chinese paintings in 2012. He said, “I’ve been looking at my dad’s old books about Chinese painting techniques and watched countless videos of masters online. I visited a Chinese painting exhibition in Hongkong in 2012. It sparked my interest. Ever since, I didn’t stop painting.”

In their artists’ statement, the Chows wrote: “When we get used to a place, the sights and sounds become too common, too familiar. When that happens, we stop seeing. We start taking things for granted and stop exploring. This is unfortunate because appreciation fades.”

Their works explore two familiar things: their Chinese heritage and their birthplace, Baguio. They wrote: “We use Chinese style painting to depict Baguio landscapes. Most art pieces may not be familiar to most people because what we tried to portray in these paintings are the uncommon landscapes we fail to recognize.”

Father and son believe a relaxed mind is key to Chinese painting. Chow the Elder said, “It is important to be relaxed because you have to have this image as if you’re floating in the air overlooking the mountainscapes. You have to execute your strokes properly. Brush stroke is very important in Chinese painting.”

At the opening, Chow the Younger explained that the Chinese way of appreciating a painting is often expressed by the words du hua, meaning, “to read a painting.”

He said, “Chinese painting is one of the oldest continuous artistic traditions in the world. Painting in the traditional style is known today in Chinese as guóhuà, meaning ‘national’ or ‘native painting’, as opposed to Western styles of art which became popular in China in the twentieth century. Traditional painting involves essentially the same techniques as calligraphy and is done with a brush dipped in black ink or colored pigments; oils are not used.”

Chino Chow welcoming guests

He cited the two main techniques in Chinese painting: gongbi, meaning, “meticulous”, which uses highly detailed brushstrokes that delimit details. This is often colored and usually depicts figural or narrative subjects. It is often practiced by artists working for the royal court or in independent workshops.

The other technique is shui-mo, ink and wash painting, loosely termed watercolor or brush painting, also known as “literati painting.” This was one of the “Four Arts” of the Chinese scholar-official class. This was an art practiced by gentlemen. This style is also referred to as xieyi or freehand style.

The Chows have remained faithful to their Chinese heritage in landscape painting while at the same time keeping their affection for the city that has blessed them so generously.

“Bi Yao” runs until Oct. 29 at the Baguio Museum, Tourism Complex, Gov. Pack Road, Baguio City

Detail from Cypress Point Irisan by Norman Chow