By YOLANDA L. PUNSALAN

RICE is the staple food for more than half the world’s population and one-fifth of the world’s population, more than one billion people, depend on rice cultivation for their livelihood.

Such is the importance of rice to mankind.

In the Philippines, November has been declared National Awareness Month to “heighten public awareness on rice and its interrelationship with malnutrition and poverty in order to sustain the attainment of global food security.”

November was chosen as Rice month because it coincides with the anniversary of the Philippine Rice Research Institute, which undertakes research and development on rice farming systems, technology and policy-making.

Yet, scanning Philippine mass media, rice-related stories are more in the negative: the abused unlimited rice promos in restos; the criminal ring brought about by cartels; the dieters’ shunning of rice as though it were poison; the hoarding of sacks of rice. And worst, the precious grain getting wet and rotten in the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) warehouses, undistributed to the intended beneficiaries—the victims of Supertyphoon Yolanda.

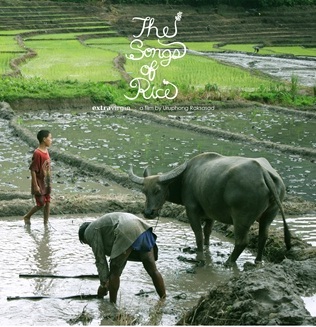

There was one instance recently that something inspiring about rice was featured. It was a Thai documentary, “Songs of Rice”, one of the entries in Cine Totoo, an international documentary festival held in Manila.

“Songs of Rice,” a film by Uruphong Raksasad, spans different seasons and provinces in Northern Thailand, in a lyrical, poetic, magical realm.

“Songs of Rice,” a film by Uruphong Raksasad, spans different seasons and provinces in Northern Thailand, in a lyrical, poetic, magical realm.

Rice stalks weave their own poetry as they flutter in orchestration in the breeze, the living green fields, framed by blue mountains. When the fields have dried and the soil has to primed, cleaned and cleared, then comes the noisy, motorized gigantic thresher, shaving the fields inch by inch, while dogs, children and the adult males skip and search the hay looking for field rats, that they hold without squeamishness by the tail. These will be roasted over charcoal in the evening for their dinner under the skies.

There are many festivals and causes for celebration. In the summertime, their carabaos looking like albinos, are bedecked with flowers and brightly colored crepe paper, then paraded into town. Lovely women in traditional, glittering costumes are enthroned in the midst of the parade. Young daughters are made to show off their graceful interpretation of Thai dances, while the adults break sweat doing community cooking, mixing rice with dozens of cans of condensed milk, for some sticky, glutinous dessert, served at the dance. The more macho farmers get to race their own carabaos bareback over mud, most of them being thrown off by the beasts of burden before they can get to the finish line.

When the climate gets colder, the farmers are too lazy to even brave the shower. “Last year, I wore the same clothes for twelve days straight”, says a farmer, “because I couldn’t go to the shower, too cold”.

Some mornings when the rice plants are almost shoulder level, a farmer in rubber boots plods through the muddy fields with a fishpole. Right there, he can catch live fish which he puts in his enclosed wicker basket at his waist.

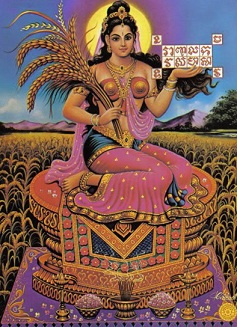

The Goddess of Rice is worshipped by all. Her framed picture is paraded during her festival through the narrow streets. The entire village is in prayer mode. A shaman feeds each worshipper with a scoop of cooked rice, direct from his fingers to each mouth, reminding each one who eats the rice, “that rice in our belly is good for life”.

During the time for remembering the dead, the living relatives bring framed portraits of their dearly departed to a site, while they do rituals of pouring oil with much respect in a canister. After time spent kneeling, each one stands to put a ball of newly cooked rice and gently places it on a ledge, as an offering for each soul—-“For mother, that if she is suffering, may her suffering end, and if she is happy, may her happiness increase.”

In joyful seasons, the entire villages outdo each other in fireworks competitions. Bunches of ten to 20 adults carry a circular frame as huge as a large inflatable swim pool of thin bamboo slats and in its center is a mixture of firepowder in heavy metal and gaily colored cloths. When lit up, the firework rises to the sky, rotating and rotating higher like a top with a loud noise, and leaving circles of smoke. The finale occurs when a parachute opens up coming from the cloths, and the circular bamboo slowly descends, with all the villagers looking up to the sky enchanted and clapping.

Such is the value the Thais give to rice. So central and essential to a native Thai’s daily diet and spiritual core. So revered by them.