Text and photos by ELIZABETH LOLARGA

PAINTER Alfonso “Dayong” Mendoza Jr. has a continuing love-hate relationship with the jeepney.

He has been a commuter for much of his life. When he looks at jeeps from the point of view of a car owner, he sees how the typical jeepney drivers’ proprietary attitude towards roads and byways enables them to defy traffic rules and road courtesies.

It is a world Mendoza is familiar with, having had to take on a regular job as coach and teacher to provide for his young family. After two well-received shows, he concentrated on training players for the Philippine Basketball League, University Athletic Association of the Philippines and the Philippine Basketball Association. Even when he was doing well as a coach, he got around in jeeps while other coaches drove BMWs or Benzes.

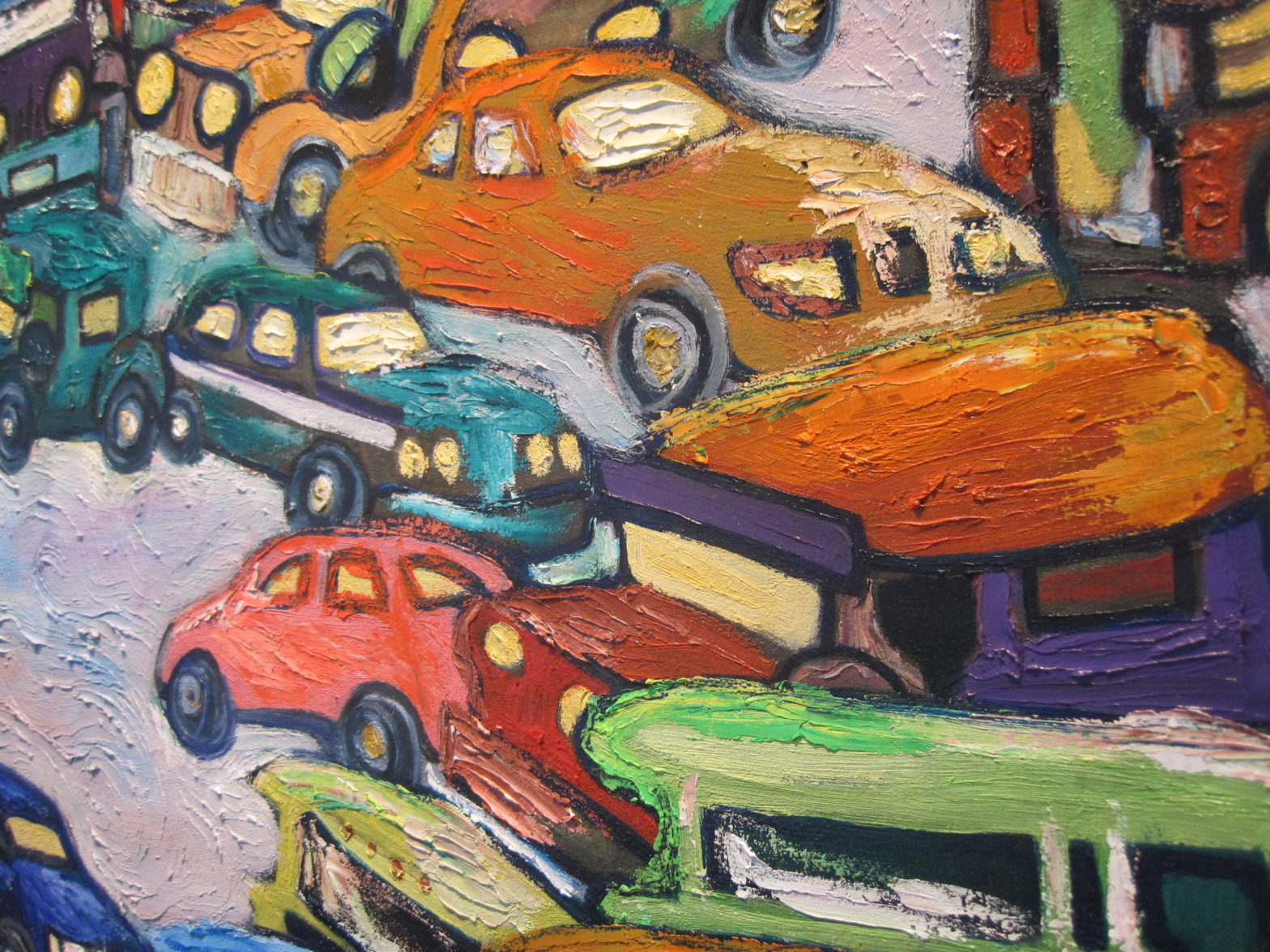

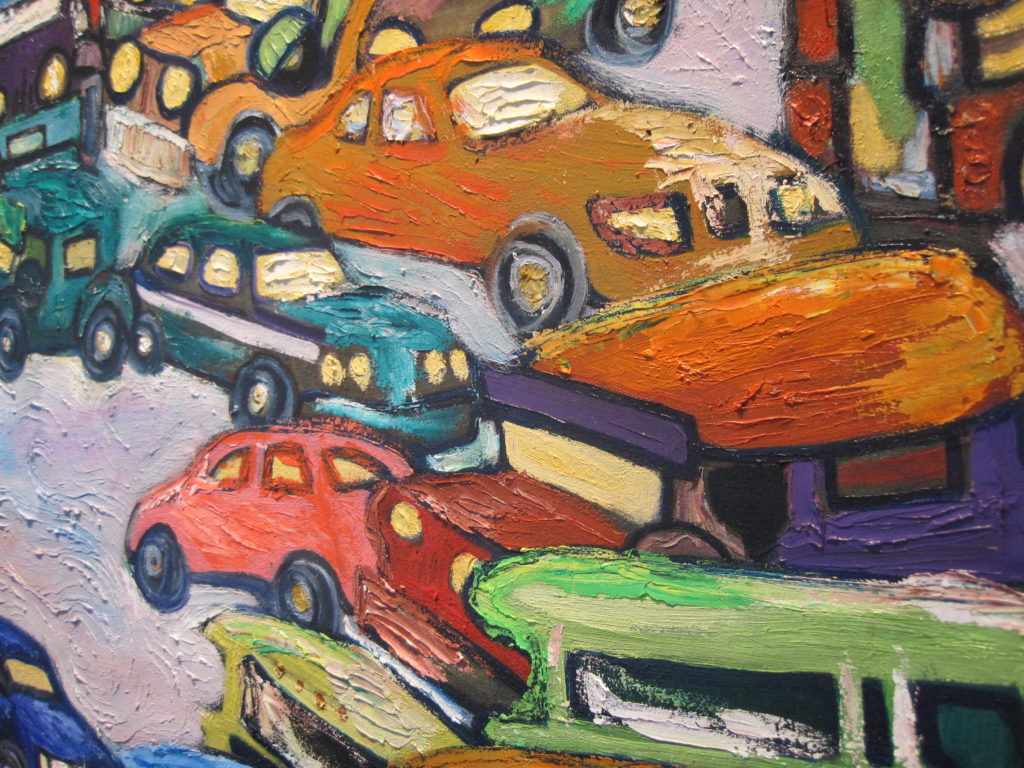

His “Dyip! Dyip! Dyip!” at Blue+Gray Gallery at L2, Serendra, Bonifacio Global City in Taguig, is his patriotic declaration of “Pinoy ako!” He looks at the jeep as a Filipino space decorated to the last and littlest corner, a space filled with loud music and passengers, each with a destination in mind. His canvases teem with stories, too, from the barker signaling only two more passengers needed so the jeep can roll off to the droopy figures of working women and men getting on board for the trip home.

Perplexed why some artists want to be judged by international standards or are pursuing these, he argues, “Why should we cater to international tastes? Shouldn’t we do subjects that we see and we know? Unless you grew up and lived for a long time in another country, shouldn’t you pick subjects that you see here?” Mendoza cites Van Gogh who painted everyday scenes seen from his small window.

Much earlier, as a boy of nine or 10, while waiting for his newsman father to finish work in Intramuros, Mendoza looked out the office window and drew versions of the Manila City Hall clock. Many afternoons that stretched to evenings, that was his subject until cartoonist Roni Santiago (famed for his “Baltic and Company”) took notice and asked him to draw something for the newspaper’s spot cartoon page.

The Mendoza of the early ’80s drew on any piece of paper that he picked up in the newsroom. He can’t forget the brush pen that Santiago gifted him and the technical pen that another cartoonist, Willy Aguino, gave and taught him how to use it. That was all the encouragement he did to start on an art path.

This was complemented by a constant exposure to the editorial cartoons and paintings of Danilo Dalena. If the Dalenas weren’t in his childhood home in Project 6, the Mendozas were in the Dalenas’ city house in Kamuning, Quezon City, or provincial home in Pakil, Laguna.

Mendoza says Dalena’s works are deep in his memory bank, adding that his Tito Danny is a true original who knew how to genuinely immerse himself in the crowds immortalized in the “Alibangbang” and “Jai-alai” series.

Not everything has been handed to him easily. Mendoza recently went through a crisis that made him decide to leave basketball coaching, a jealous spouse, he calls it, so he can resume painting full time.He adds that he doesn’t want his recent sadness to be an excuse for doing gloomy works.

At last year’s launch of Martial Law Diaries, where his parents were among the contributing writers, he renewed acquaintance with Vic Wenceslao of Blue+Gray Gallery who asked him to paint again and submit a work for the Manila Art Fair. He turned in “Biyaheng Langit,” a large painting at 65.5 x 47.5 inches that captures the bedlam of urban gridlock, not just along EDSA but in any part of the Philippines where jeepneys rule.

Since then, Mendoza has kept the painting momentum going. He says though that he didn’t put his oils and paints totally aside while fulfilling his role as breadwinner–he accepted commissioned work that sometimes included portraits of pet dogs and cats.

While preparing for his third show, he realized something about himself. “It’s ironic that even as I am an impatient person, with the slow-drying medium of oil, I am so patient. While waiting for an area to dry, I work on another area. Sometimes, I paint simultaneously.”

What helped raise his spirits, apart from a Bible study group, was having his own studio space, at last. He says, “The feeling is wonderful. When I wake up, I see all the paints and canvases lined up. It’s as though they are waiting for me and wishing me a good morning. I do a full day’s work. When it’s time to sleep, I take a peek at the studio and wish them [his materials] good night.”