[metaslider id=29231]

By YVONNE T. CHUA

THE more than 30,000 classrooms the national government is building this schoolyear will look hardly any different from those constructed in recent years, especially to the untrained eye.

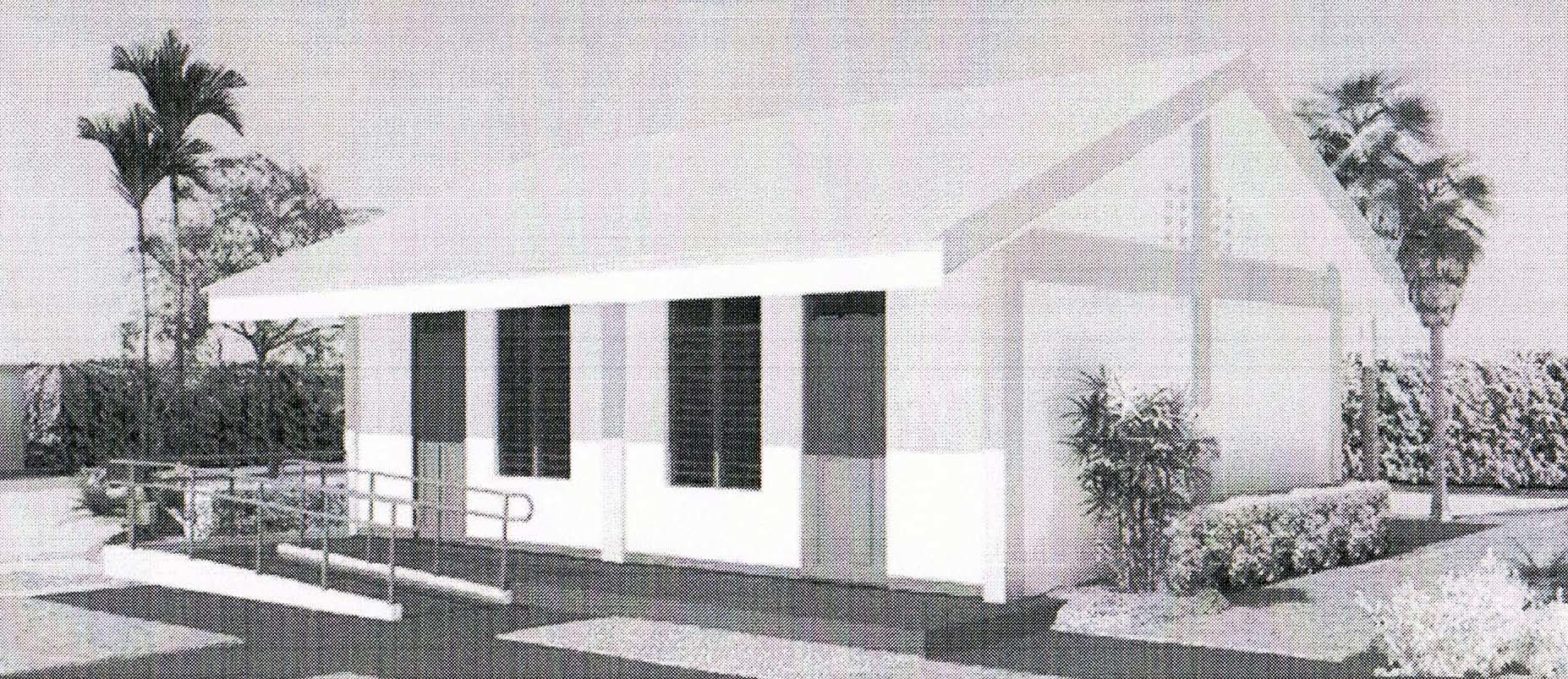

But the classrooms of 2014 and thereafter will be different. They will sport a new design the Department of Education says can withstand deadly earthquakes and storm winds of up to 250 kph, more ferocious than those unleashed by supertyphoon “Yolanda” in November.

The shift to calamity-resilient school buildings entails structural changes. These, though, will not be visible when construction is done, and thus pose a challenge to school communities, civil society monitors and state agencies like DepEd and the Department of Public Works and Highways that implement the government’s school building program: How to make sure that contractors follow the specs to the last detail.

“(T)hese improvements will be meaningless if we cannot implement (or) execute the design as planned,” said engineer Annabelle Pangan, who heads the DepEd’s Physicial Facilities and Schools Engineering Division that developed the new design in coordination with the DPWH.

“Monitoring is key,” she said.

The new design will apply to school buildings the DepEd and DPWH are erecting—from single-story one-classroom to four-story 24-classroom structures—using money mostly from the Basic Educational Facilities Fund (BEFF) provided in the national budget and the Philippine Amusement and Gaming Corp.

To make each building more resilient to earthquakes, the DepEd is banking on a bigger footing or base and thicker beams and columns. It now requires a tie beam even for a single-story school. The horizontal beam connects several columns to make the structure stable.

The DepEd’s answer to strong typhoons is a combination of steel truss roofing, roof framing support that uses J-bolts, thicker roofing sheets and ridge roll, thicker and more reinforcing bars or rebars for roof beams, and a drop ceiling.

The pre-2014 design uses steel rafters for roof framing, teck screws for framing support, and a cathedral type ceiling.

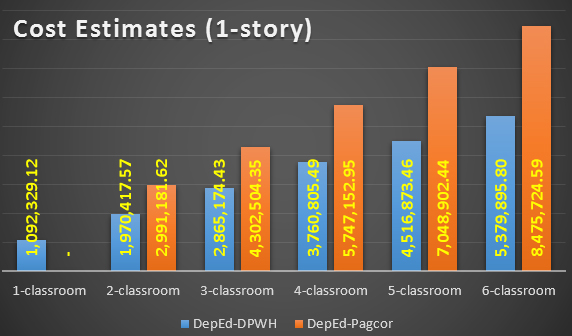

The structural enhancements have raised the cost of a complete one-story one-classroom building with basic features from P685,000 to nearly P1.1 million, or 60 percent more expensive.

The structural enhancements have raised the cost of a complete one-story one-classroom building with basic features from P685,000 to nearly P1.1 million, or 60 percent more expensive.

The basic features include concrete and smooth finish flooring, smooth plastered walls, painted walls and ceiling, a complete set of windows, two entrances with doors for each classroom, complete electrical wires and fixtures, built-in curved chalkboard, ramps that comply with the Accessibility Law and toilets.

Schools to be built out of Pagcor money are even more expensive. They will be fitted with special features such as a pediment façade, stage, concrete parapet, decorative balcony railings and wider corridors.

A one-story two-classroom Pagcor-funded building is estimated to cost almost P3 million, or a million pesos more than one with just the basic features.

Becausethe new buildings are costlier, the DepEd has had to revise the number of new classrooms it is building this year.

With the old design, this year’s P39 billion BEFF could have built 43,000 classrooms, which the DepEd estimated to be the shortage when it was preparing its 2014 budget. With the new design, only about 32,000 new classrooms will be built.

Introduced to the 2005 national budget, the BEFF, formerly the Schoolbuilding Program for Areas Experiencing Acute Classroom Shortage, is on top of the P1 billion allotted annually for the Regular Schoolbuilding Program.

Covered by the 19-year-old Republic Act 7880 or the “Roxas Law” (after its author, then Rep. and now Interior Secretary Mar Roxas), funds for the Regular School Building Program have often been considered another “pork barrel” fund of lawmakers. The pie is divided among legislative districts, half depending on the district’s student population in relation to the country’s total student population, only 40 percent on classroom shortages, and the remaining 10 percent on DepEd’s discretion.

The Roxas Law further requires the DepEd to first consult the representative of each legislative district when identifying projects for the Regular School Building Program. For decades, lawmakers have been known to exert pressure on DepEd and DPWH officials to include schools in the list even when the need is not urgent, or, worse, to award projects to favored contractors.

The BEFF for new classrooms in areas with acute shortage has, meanwhile, dramatically risen over the years, from P1 billion in 2005 to P7 billion in 2012, P14 billion in 2013 and P39 billion this year.

The Ateneo School of Government, whose civil society monitors looked into the construction of 380 school buildings in 20 schools divisions funded by last year’s BEFF, said in a report it did not detect “politician intervention” in these projects.

At present, the DepEd prescribes the design and the list of classrooms to be built using the BEFF, and the DPWH bids out and supervises the projects.

This year, the DepEd is building 2,500 classrooms in Yolanda-ravaged areas in Eastern, Western and Central Visayas. A total of 561 classrooms will be built through the BEFF; 1,338 through a P2 billion Pagcor fund, and 500 through donations from the private sector, foreign governments and development agencies.

Unlike the BEFF, the DepEd, and not the DPWH, is in charge of engaging contractors for the Pagcor schools.

But because both the DepEd and DPWH are still in the procurement stage, the new classrooms in the Yolanda-affected areas and the rest of the country will not be ready when classes start on Monday, said Pangan.

It will take 60 to 90 days to construct a one- or two-classroom building and six months for a multistory building, she said.

Students in areas stricken by Yolanda will thus have to make do with existing structures as well as makeshift ones that serve as temporary learning shelters or TLS.

Students in areas stricken by Yolanda will thus have to make do with existing structures as well as makeshift ones that serve as temporary learning shelters or TLS.

Each costing about P60,000 to P74,000, more temporary learning shelters will be built this year, especially in places marked as “no-build zones” (within 40 meters from the coastline) and where schools need to be relocated, Pangan said.

As the structural components of the calamity-resilient buildings “can’t be seen from the outside,” Education Undersecretary Franciso Varela acknowledged in a forum in mid-May that monitoring the school building program will be even more challenging than in the past.

The Ateneo report listed several problems in the school building projects it tracked last year. Two in three projects experienced delays of from 83 to 166 days. Some contractors deviated from the program of work. Several DPWH district engineers and contractors reported 100 percent completion for unfinished classrooms. Substandard materials were used in some classrooms, resulting in cracks in walls, floors and ceiling and broken door knobs and window jalousies in less than a year.

The report noted limitations in government monitoring of classroom construction arising from insufficient resources, geographical constraints and the absence of a mandate to enable school-based monitoring. Monitoring, it said, is largely ad hoc, especially in schools.

As well, classrooms built by local governments almost always do not follow DepEd-prescribed standards, complicating the job of the monitors.

To better watch the construction of the newly designed calamity-resilient school buildings, the DepEd is hiring 44 more engineers to augment its current pool of 175 engineers deployed nationwide, Pangan said. The DPWH has also hired 120 cadet engineers for the BEFF-supported projects.

Together with school heads, the engineers will be oriented on construction monitoring using materials developed by, among others, the Japan International Cooperation Agency (a simplified construction handbook) and the Australian government (an instructional video on classroom construction).

But whether they’re in or out of government, individuals and organizations monitoring classroom construction would do well to watch it from beginning to end.