By YVONNE T. CHUA

The 15-year Education for All (EFA) global movement is drawing to a close this year, and the verdict is out.

Only a third of the 164 governments that pledged to achieve universal primary education and five other goals by 2015 have done so, according to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) in the report Education for All 2000-2015: Achievements and Challenges released this week.

By its own admission, the Philippines isn’t among those that have made the mark.

In a report it submitted to Unesco in time for the World Education Forum scheduled in Incheon, South Korea next month, the Philippine government acknowledged that the strides it has made in achieving in several EFA goals have “been too slow to make it to target by 2015.”

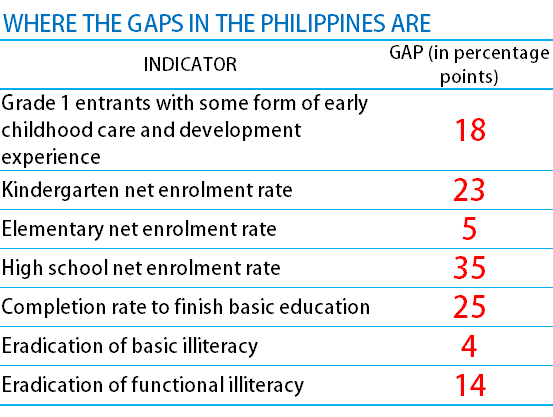

The Philippine Education for All (EFA) 2015 Review report identified gaps in:

- Grade 1 entrants with some form of early childhood care and development experience: 18 percentage points

- Kindergarten net enrolment rate: 23 points

- Elementary net enrolment rate: 5 points

- High school net enrolment rate: 35 points

- Completion rate to finish basic education: 25 points

- Eradication of basic illiteracy: 4 points

- Eradication of functional illiteracy: 14 points

The Philippine report also expressed concern over boys being at a disadvantage, from getting into school, and staying there, to recording lower literacy and academic achievement rates than girls.

Despite the problems, Unesco still considers the Philippines among the countries still likely to achieve some of the EFA goals in the coming years if it keeps up its efforts.

One such goal, Unesco said in this year’s report, is achieving the 80 percent gross enrolment ratio where the Philippines is among the governments that have made “strong progress” and are “moving forward.”

Gross enrolment ratio is the total enrolment in a given level of education as a percentage of the population that should be enrolled at this level. Net enrolment ratio is the ratio of the enrolment for the age group corresponding to the official school age in the school to the population of the same age group in a given year.

The six EFA goals, adopted in Dakar, Senegal in 2000, are early childhood care and education, especially for the most vulnerable and disadvantaged children; universal primary education, or access to and complete free and compulsory primary education of good quality for all children; equitable access to appropriate learning and life skills programs for youth and adults; a 50 percent improvement in levels of adult literacy by 2015; gender equality; and improved quality education.

“There has been tremendous progress across the world since 2000—but we are not there yet,” Unesco director general Irina Bokova said in the foreword of Unesco’s latest report of EFA. “Despite all efforts by governments, civil society and the international community, the world has not achieved Education for All.”

As a result, she called EFA 2015 a “qualified success.”

Unesco said only half of all countries have achieved universal primary enrolment, with still 58 million children out of school and around 100 million failing to complete primary education.

The poorest children are “four times more likely to be out of school and five times more likely not to complete primary education than the richest,” Bokova said.

The Philippines is among the countries where the Unesco report said inequality in education persists.

The Philippines is among the countries where the Unesco report said inequality in education persists.

Unesco cited inequality in the transition from elementary to high school in the Philippines where only 69 percent of grade school graduates from the poorest families continued into high school, compared with 94 percent of those from the richest households.

The situation has hardly changed since 2003, it said.

Unesco said immunizing children against common and preventable illnesses is important not only to their overall health, but also to their readiness to learn and subsequent schooling.

But it noted the gaps between the richest and poorest households in immunization coverage, and identified the Philippines as among the countries that have seen little improvement in the total percentage of children fully immunized.

And while the Philippine government has recognized the problem of more boys than girls not getting into school or are leaving school, Unesco said its “gender equality mechanisms and policies focus largely on women and girls.”

Unesco has conducted site visits to the Philippines and other countries to find out if schools are child-friendly. It identified poor school infrastructure and lack of maintenance as major problems. Only one in three schools in the Philippines were declared to be in good physical condition—without broken windows or peeling paint.

The Unesco also found that the official intended instructional time is not the same as actual learning time in some countries. For example, one-third of pupils in the Philippines, as well as Argentina and Paraguay, reported problems with teachers’ late arrival, absenteeism and skipping class, it said.

The Philippines also counts among the countries where computer resources are greatly overstretched, especially in primary schools, in the process hindering the use of information and communication technology to improve learning.

Over 100 learners share a single computer at the primary level in the Philippines, the report said, citing data from Unesco’s database.

The Philippines also hasn’t fully decentralized governance of basic education, according to Unesco. The national government still sets the curriculum content, instructional time and teacher salaries, and allocates resources to schools, although it leaves the choice of teaching methods and support activities for students to schools, it noted.

Programs such as the cash transfer, school feeding, compulsory kindergarten education, the multisector approach to early childhood services and textbook monitoring that have contributed to improving access to and quality of Philippine education were, however, held up as good examples in the Unesco report.

Because of the setbacks, the Unesco report urged all government to complete the EFA agenda by pursuing a “Post-2015” agenda, which sets 2030 as the target date of completion.

The Philippine EFA 2015 Review report said it is addressing “emerging and persistent” issues that threaten the achievement of universal education such as poverty, climate change, devastating disasters, armed conflict and threats to the safety and security of schoolchildren.

It unveiled the Philippine EFA 2015 Acceleration Plan that will pursue strategies to attain education of all in the coming years.

The report also said the government has identified long‐term targets to guide education development beyond 2015.

Alternative learning system will be enhanced, the standards of Early Childhood Care and Development programs raised, the quality of the K-12 basic education program improved, teaching and learning methods enhanced, ICT adopted for education, and education organizations and institutions strengthened, according to the report.