Queen Sofia’s photo by CASA DE S.M. EL REY / BORJA FOTÓGRAFOS

IF you are a Filipino, most likely you can understand the Spanish headline above.

Because of 300 years of Spanish colonial rule, Spanish is part of Filipino culture since Ferdinand Magellan discovered the Philippines in 1521.

There are about 20,000 Spanish words in Filipino. In spite of that, however, the Philippines — unlike Latin America — never became a Spanish-speaking nation. The conquistadors never taught the language to perpetuate the disunity of the archipelago and maintain their rule over the natives, who were scattered over 7,100 islands, 10 languages and 70 dialects.

A Spanish colonial official asserted: “Experience has taught us that those who know our language are almost always the most headstrong … the ones who talk behind our back, criticize and rebel.”

Fast forward to the present. In June last year, on her fourth visit to the Philippines,Spain’s Queen Sofia encouraged Filipinos to learn Spanish “not only because it is part of the cultural heritage of the Philippines but also because it opens up opportunities to secure the well-being of future generations of Filipinos in a globalized world.”

For the past few years, Spain has been making efforts to renew ties with its former Asian colony, while acknowledging its errors during its days as a colonial master.

Spanish delegates at a recent forum of Spanish and Filipino diplomatic, cultural and tourism officials held recently in Makati City, envisioned Manila as Madrid’s door to Asia and vice versa.

To bridge the gap between the two countries, Instituto Cervantes Secretary General Rafael Rodriguez-Ponga told the Tribuna España-Filipinas forum, both countries must rediscover each other. That includes Filipinos learning the language that was once denied them.

“This goes beyond historical relations. It is not just about bridging the gap to the past but also charting the pathway to the future,” said Rodriguez-Ponga, who is the worldwide head of Instituto Cervantes. “We should recognize that relationships between the Philippines and Spain, whether it be in stone or on paper, is working for the future of both countries.”

Also, how Spanish tourists react with familiarity when they visit Intramuros, the original walled city of Manila, underlines the large tourism market from Spain and Latin America that is just waiting to be tapped.

“It was like being in Latin America because Intramuros looked like Cartagena or Quito. It looked like a colonial city in the 16th or 17th centuries. It felt very familiar,” said one Spanish delegate at the Tribuna, Teresa Aguado, vice rector at the Madrid-based Spanish National University of Distance Education.

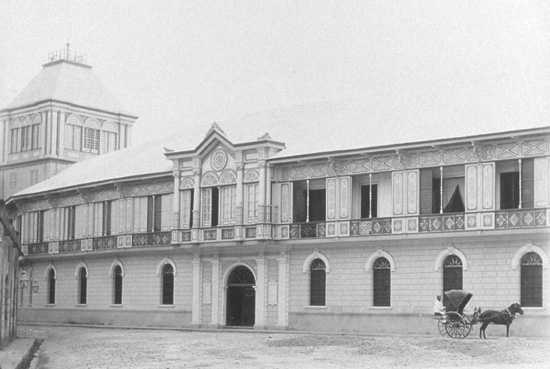

Colegio de San Juan de Letran was known for its Spanish when the language was in the curriculum. Established in 1620, it is the Philippines’ oldest college and the only learning institution put up by the Spaniards that remained at its original site in Intramuros.

Colegio de San Juan de Letran was known for its Spanish when the language was in the curriculum. Established in 1620, it is the Philippines’ oldest college and the only learning institution put up by the Spaniards that remained at its original site in Intramuros.

To this day, Letranistas cheer “Arriba Letran!” in the annual NCAA inter-collegiate intramurals — a legacy of Letran’s Spanish heritage. The college hymn is in Spanish.

Because of the lack of teachers wrought by the abolition of Spanish, the task of reintroducing the language fell on Spain’s cultural arm, Instituto Cervantes.

When the teaching of Spanish was abolished from the Philippine educational system in the mid-1980s, Filipinos felt that it was a language that belonged to a bygone era. Besides, English was the worldwide language of business. But the Internet changed all that in the mid-1990s, speeding up globalization.

English is a legacy of American colonial rule that began with the Philippine-American War. In 1899, the United States refused to recognize Philippine independence and took over from Spain as the new colonial master.

However, American soldiers, following Washington’s policy of “benevolent assimilation” in its annexation of the Philippines, began teaching their language to Filipinos even before the war officially ended in 1902.

English was the primary subject when pioneer American teachers arrived in 1901 to set up the country’s public education system. Filipinos saw that the new conquerors would not be as harsh as the Spaniards and embraced English — making it the Philippines’ lingua franca.

But now, changing demographics in the United States, where a million Filipinos reside, might bring about a Spanish renaissance in the Philippines. Spanish is the second largest language in the United States because of the influx of immigrants from Latin America, particularly from Mexico — another country that the Philippines shares cultural and historical ties with. Instituto Cervantes estimates the United States to become the largest Spanish-speaking country by 2050.

English enabled the Philippines to come from behind and grab the top spot from India in the call center industry. Rodriguez-Ponga said learning Spanish opens the door to Latin America, not just Spain and America. Not to mention that the Philippines can become Latin America’s door to Asia.

One precaution, though. Not all Spanish words mean the same in the Philippines. Spaniards speaking to Filipinos, for example, must be clear when talking about their querida or someone dear to them. In the Philippines, querida (“kerida” in Filipino) means “mistress”.

On other hand, Filipinos visiting Mexico or any other Spanish-speaking country would do well to take care when introducing Filipino rice cake delicacies to the locals by not asking them if they want to try some puto. Depending on the usage, it means “male prostitute” or “bastard”.