The Covid-19 pandemic deepened the dire straits of Filipino nurses, which is why comedy skits parodying their working conditions or even their provincial accents add insult to their plight. It’s not surprising why most nurses, overworked and paid a pittance, move heaven and earth to seek employment abroad — resulting in a worrying nursing drain in local hospitals and clinics.

Last year, the Philippines grappled with a shortage of 127,000 nurses. That number is expected to jump to 250,0000 in 2030, according to www.hospitalmanagementasia.com. In that website, Everrette C. Zafe, nursing director of World Citi Medical Center in Quezon City, identified Covid-19 as the tipping point for the exodus.

“Before the pandemic, the pace of hospital recruitment was keeping up with the pace of those leaving, but the balance was disrupted by Covid,” said Zafe. “Nurses feared the risk of catching the virus themselves and we saw an exodus of nurses, with many leaving the profession altogether.”

Historically, the diaspora of Filipino nurses started during the American occupation of the country. The training of Filipinos as nurses led to their mass migration to the United States.

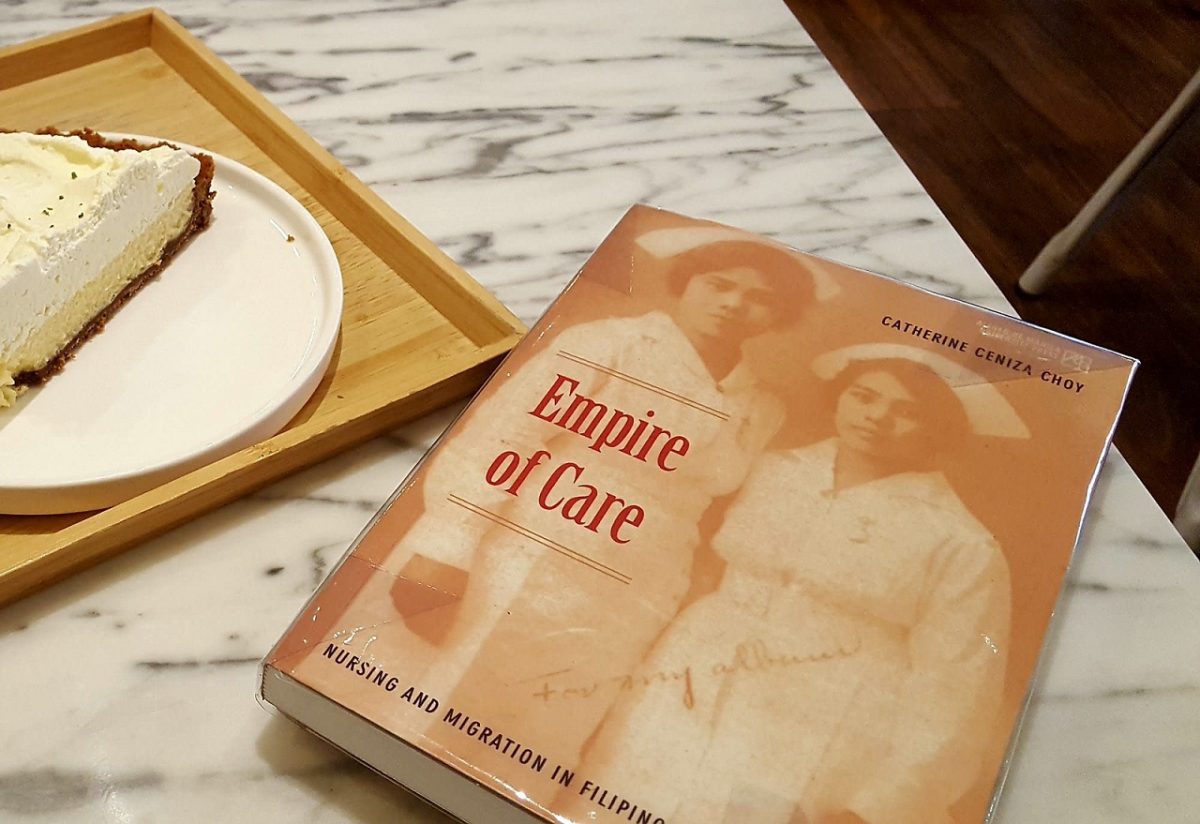

Catherine Ceniza Choy, ethnic studies professor at the University of California, Berkeley, traces this phenomenon in her book “Empire of Care: Nursing and Migration in Filipino American History” (published by Ateneo de Manila University Press). She critiques, among other things, the rhetoric of Filipino nurses’ migration as a good outcome of US colonial rule. She argues that the definition of “good” is taken out of its global, historical context, simplifying the complex US-Philippine colonial relationship, romanticizing America’s ability to provide opportunities for Filipino nurse migrants, and erasing the effects of US imperialism.

Training Filipino women

The narrative of US colonial benevolence began when Americans trained house-bound Filipino women as nurses. Patrocinio Montellano, one of Choy’s 43 interviewees, found her four-year US sojourn in the 1920s enjoyable. As a nurse in Honolulu and New York City, she traveled throughout the country and took postgraduate courses in nursing education in San Francisco, Cleveland, and Washington, D.C..

Comparatively, Spain’s colonial education system was retrograde vis-à-vis the American system. Choy says that only a limited number of Filipino girls received primary education in Spanish charitable institutions, with women receiving high education only when a School of Midwifery was founded in 1879.

Nurse training closely followed the US system, which was gendered, classed, and sexualized, according to Choy. The nursing classes only accepted women from Filipino families considered respectable, reflecting the trend then in Victorian America of selecting “young gentlewomen with virtues and qualities of middle- and upper-class womanhood” for the profession. America reworked the mid-19th century concept and image of nursing as the work of “white, native-born, poor, and older women at the end of their working lives.”

The criteria for choosing Filipino nursing students were “good and sound physical mental health, good moral character, [and] good family and social standing,” together with “recommendations from three different persons well known in the community,” Choy writes.

The nursing students went through regular first-year classroom study at the Philippine Normal School from 1907 to 1910 and were separated for their practical work at St. Paul’s Hospital, Philippine General Hospital (PGH), and St. Luke’s Hospital. By 1910, both classroom and practical nursing work were being completed in the individual hospitals, just like in the United States. The subjects were “practical nursing, materia medica, massage, and bacteriology,” complemented with lectures on “medicine, communicable diseases, and operating room techniques.”

Integral to nurse training, highlights Choy, was learning English, which “was [a]… unique aspect of American colonial education in general and medical training in particular.” A Bureau of Health (BH) representative tutored the PGH students in English once a week for two and half years.

Civilizing ‘monkeys’

Nursing in the Philippines was also the narrative of the American Dream fortified through the Americanized nursing programs taught by medical and nursing supervisors who were reluctant to teach in the Orient. They were eventually persuaded by another narrative of their service as “an exotic travel adventure” in the Philippines. The teaching post entailed “interesting stops” in Hawaii, Japan, Shanghai, and Hong Kong en route to the Philippines, offering them a glimpse of “Oriental life, manners and customs, indelibly impressive and broadening,” says Choy, quoting BH supervising nurse Mabel McCalmont.

The return trip was no less grand. It was via Europe, completing “the circle of the globe and gaining an experience which is the desire of many.”

Tellingly, the “tour package” was a rebranding of the 19th-century zeitgeist of “Manifest Destiny,” justifying the colonization and civilization of the “monkeys.” (Admiral George Dewey called the Filipinos “monkeys” and was ordered by his superiors to distance himself from them, writes Desiree Ann Cua Benipayo in “Honor: The Legacy of Jose Abad Santos.”)

Laboratory studies were conducted on the Igorot and their stools in the early 1900, and the findings reinforced the Americans’ prejudicial perception of Filipinos as a “potentially dangerous type, a carrier of germs, parasites, and pathogens,” and “not a strong or enduring race.” Conversely, the study showed Americans as resilient and able to withstand the tropical climate.

The zeitgeist synchronized with the nurses’ view of their profession, like Lavinia Dock, an activist in the professionalization of US nursing and internationalization of professional nursing. For Dock, says Choy, diseases like those afflicting infants, as well as smallpox, cholera, tuberculosis, and malaria, were hampering the Filipinos’ progress; thus, to improve the Filipinos’ lot, teaching nursing was “absolutely build scientific and industrial education on a substantial foundation.”

Choy puts it in another way in an interview with news.berkeley.edu: “To uplift Filipinos, [Americans needed] to educate them in American ways.”

Better everything

The American Dream became the dream of Filipino nurses given their low wages and lack of professional respect in the Philippines. Choy says that in the mid-1960s, some government agencies paid nurses lower wages than janitors, drivers, and messengers. They were earning about ₱200 to ₱300 monthly for working six days a week, including holidays and overtime.

Comparatively, general duty nurses in the United States during the same period received around $400 to $500 per month. Interviewee Ofelia Boado recounted to Choy that her salary was “good for what we get in payment” in Philadelphia. Others bought “stereos, kitchen appliances, and cosmetics” that only “the affluent elite in the Philippines” could afford, and indulged in Broadway shows, Lincoln Center performances, and travel within the United States, says Choy.

Boado relished the independence: “You have your own apartment. In the Philippines, you live in a dorm, where everything closes at 9 p.m. Or even if you stay at home, you don’t go home late.”

Exchange Visitor Program

The Exchange Visitor Program (EVP), established in 1948, unintentionally paved the way for the mass migration of Filipino nurses to the United States in the 1960s. The EVP countered the “hostile propaganda campaigns” of the Soviet Union during the Cold War while introducing US culture and democracy globally, writes Choy.

Participants from Europe and Asia had a two-year visa to work and study in the United States and a monthly stipend. They were required to return to their country of origin after the program.

Filipino nurses became the majority in the EVP. They liked it primarily because they believed in the prestige attached to working and studying abroad. Their experience gave them socioeconomic mobility.

Choy says the perception was fostered by the racialized hierarchies in the Philippines that were shaped by the intersecting Spanish and US colonizations. She continues: “Filipino nurses…contributed to the perpetuation of this prestige, [believing] their experience abroad carved an international avenue of recognition and authority for themselves.”

The EVP also extricated nurses from unjust situations. Milagros Babara told Choy that she applied to the program to avoid evening work shifts because she had difficulty getting home. Hermila Rabe saw it as an escape from the favoritism at her workplace where, she said, she was bypassed for the position of chief nurse by a junior nurse who was close to the hospital director.

The US Immigration Act of 1965 expedited the Filipino nurses’ diaspora to America, with the new occupational preferences enabling them to become permanent residents. Of the new system’s seven visa categories, two catered to skilled immigrants: professionals, scientists, and artists of exceptional ability (third visa category) and skilled and unskilled workers in occupations with labor shortage (sixth visa category).

The majority of the immigrants from the Philippines, writes Choy, were doctors, engineers, nurses, and scientists. The total number of engineer and scientist immigrants reached more than 4,300, and the nurses and doctors numbered 3,222 and 2,813, respectively, from 1966 to 1970.

Cheap labor

But the success stories did not stamp out the dark side of the US sojourn. The nurses, Choy relates, met with unsatisfactory conditions — lack of proper housing, and “discriminatory work conditions, and inadequate orientation programs [or lack thereof] at their sponsoring hospitals.” Worse, some were exploited and made to work as nurse’s aides or paid minimally despite doing the work of a registered nurse. Others were assigned to work in undesirable hospital areas and shift hours and were subjected to sudden changes in work schedules, while their American counterparts got the better working schedules and conditions.

The Filipino nurses were transformed from exchange visitors into cheap labor of “many sponsoring hospitals…to alleviate [the] growing nursing shortages in the post-WW II period,” writes Choy.

Significantly, the EVP didn’t lose its luster, with more than 3,000 Filipino nurses participating in it between 1967 and 1970.

Per Al-Jazeera, the exploitation of Filipino nurses in the United States continues to this day. America is facing a shortage of nurses and will need an additional 450,000 by 2025 — a gap that vulnerable Filipino nurses are eager to fill. In his account to Al-Jazeera, Ariel (not his real name) said it has been a nightmare working in the United States and treated as cheap labor. He wants to quit, but would have to pay $40,000 to get out of his contract early. Also, he said, he had been threatened against doing so by his recruiter.

Asian hate

Filipino nurses in the Philippines and in the United States found themselves in trying situations during the pandemic. In the Philippines, they faced vulnerability to the virus, inadequate personal protective equipment, and measly pay. In America, apart from exposure to viral infection, they grappled with hate and anti-Asian sentiments.

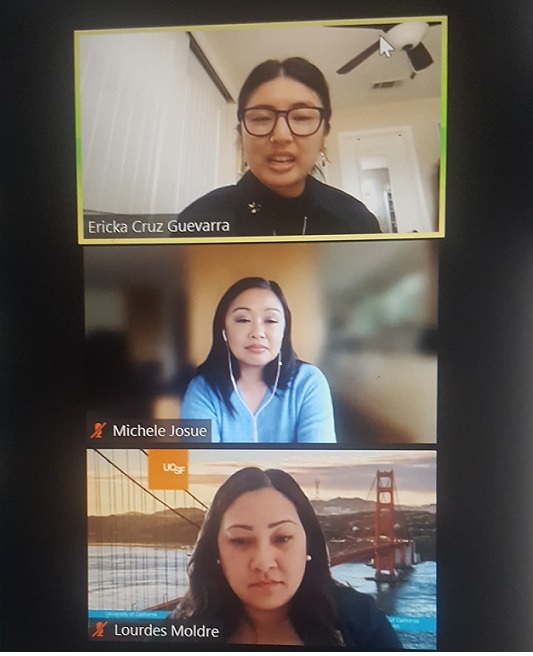

Michele Josue’s “Nurse Unseen,” the featured documentary at the 10th Annual Immigration Film Festival held in Washington, D.C. in October 2023, chronicles the experiences of Filipino American nurses during the pandemic.

“It encapsulates what our community went through. I come from a long line of nurses [and] I wanted to honor them. It highlights experiences about love and compassion,” Josue said of her film in the webinar “Nurse Unseen: Filipino nurses in the time of the pandemic and anti Asian hate” conducted by the online magazine Positively Filipino last April 4 (US time).

Josue, a Los Angeles-based filmmaker, had been wanting to do a film on the health care industry’s unsung heroes in the Philippines and in the United States. The pandemic gave her the impetus to proceed.

“The burnout and anti-hate were the topics that came into the narrative. The bigotry and hatred were a different pandemic that made its way into the film,” said Josue, who drew inspiration from Choy’s book in the struggles and experiences of Filipino nurses in the United States.

Another panelist in the webinar, Lourdes Moldre, said it was challenging working during the pandemic. Moldre, who also comes from a family of nurses, has more than 20 years of experience working as a nurse. Currently, she’s the nurse executive patient care director at UCSF Health, San Francisco.

“Filipino nurses [were] in critical areas so patients [were] more complex [and] exposed exponentially to the virus. Some nurses would stay home, but Filipino nurses were going to work,” recalled Moldre.

Her staff — Filipino or not — faced harassment. A Tibetan staff member got her hair pulled while she was on her way home. Another was unceremoniously dismissed by a patient who demanded a white nurse.

“Filipino nurses [were] vulnerable to the virus, which speaks of [the] caring nature of Filipino nurses. It speaks to the honor of being a nurse, but sets them up to be vulnerable,” added Josue.

Collective voice

The film “Nurse Unseen” raised salient points of Asian hate and misogyny being intertwined, and Filipinos and Asians experiencing dual violence at the workplace and on the streets. Webinar moderator Erika Cruz Guevarra said 11, 000 unreported acts were committed against Asian Americans in 2020.

Moldre was moved to “rise up and have our presence [felt) in our community” while simultaneously working and dealing with Asian hate during the pandemic. Josue’s film strengthened to highlight the nurses’ often unrecognized public service. Moldre, after learning there were 70,000 undocumented Filipinos in America without access to vaccination, went out and provided care.

“I wasn’t like that before. Covid woke me up as a leader,” Moldre declared.

Josue said she purposely included images of nurses standing up to the hatred in the film. She said she wanted to show that Filipinos are not quiet but “a strong community of leaders who take care of one another and speak out,” and that “Filipino nurses have a strong history of organizing.”

No reason to stay

Filipino nurses are still heading abroad despite the exploitation, discrimination, and violence. Predictably, they will continue to answer the call of the “US nursing labor demands, given that economic conditions in the Philippines are still precarious, and any improvement will not soon close the differences between [the US and the Philippines),” contends Choy, quoting Paul Ong and Tania Azores, authors of “The Migration and Incorporation of Filipino Nurses.”

The numbers present the picture. Per dw.com, nurses in Philippine public hospitals and agencies earn only ₱36,000 a month and those in private hospitals only ₱15, 000, said Eleanor Nolasco, president of Filipino Nurses United (FNU). The entry-level salary of nurses is $3,800 in the United States and £1,662 in the United Kingdom, said Jocelyn Andamo, FNU general secretary, in www.asianews.it.

To keep Filipino nurses home, Andamo said, the entry level salary must be increased to ₱50,000, contractual nurses must be regularized, and a nurse-patient ratio of 1:12 must be maintained. (The current ratio stands at 1: 20-50 at every shift.)

During the pandemic, the Philippine government implemented a temporary ban on the deployment of nurses abroad, and the Clinical Care Associate Program allowed the employment of nursing graduates who had yet to pass the board exams.

But the nurses are not staying. Currently, Germany is looking to the Philippines to ameliorate its nurse shortage that is expected to worsen between 2030 and 2040 as its aging population begins to need increased care, said dw.com. There are about 6,000 Filipino nurses working in Germany, with 2,000 migrating to that country through the government-to-government program.

Globally sought

It’s been decades since the EVP’s implementation, but Filipino nurses continue to seek work in the United States and other countries offering salary packages and better working conditions. They seem to be on top of their game, like other Filipinos working overseas. They are globally sought because of their competence, compassion, professionalism, and proficiency in English. Locally, they are hailed as heroes. But behind the scenes, in and out of the country, they fall back on the much vaunted — and hackneyed — Filipino traits of resilience and endurance to survive.

From foreign exchange visitors, Filipino nurses now epitomize the Philippines’ major export product of cheap labor, with their remittances supporting not only spouses and children but also clan members, and ultimately propping up the Philippine economy.

The situation continues to be bleak, with the pressing shortage in health care workers not easily resolved. Per inquirer.net, Health Undersecretary Maria Rosario Vergeire said it would take 12 and 23 years to ease the shortage in nurses and doctors, respectively.

It’s obvious that Filipino nurses will continue to seek employment overseas if nothing worthy comes their way at home. They must be given sufficient reason to stay. Otherwise, they will continue to observe International Nurses Day on May 6 elsewhere in greater numbers, depriving their own country of the gift of their service, skill, and compassion.