[metaslider id=30916]

By YVONNE T. CHUA

THE Philippines and three other ASEAN members count among the top 20 developing countries in the world identified as the biggest exporters of illicit capital over the last decade, according to a global report.

THE Philippines and three other ASEAN members count among the top 20 developing countries in the world identified as the biggest exporters of illicit capital over the last decade, according to a global report.

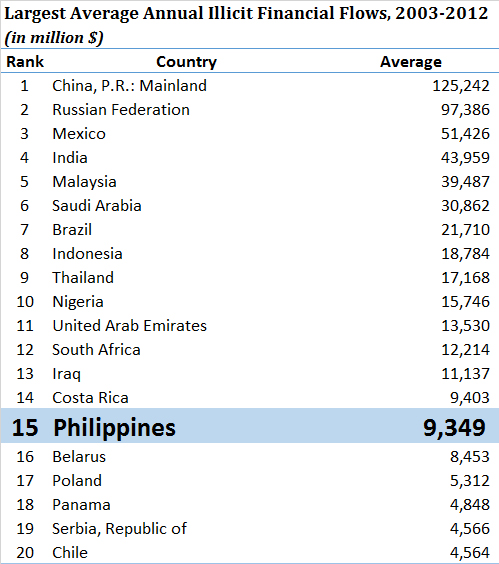

The report, released worldwide Monday (Tuesday in Manila) by Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a Washington D.C.-based research and advisory organization, ranked the Philippines 15th largest in average illicit financial flows between 2003 and 2012.

An average $9.439 billion dollars illicitly left the Philippines every year over the period primarily because of trade misinvoicing, a problem that besets many developing and emerging economics, according to GFI.

Trade misinvoicing involves manipulating the price, quantity or quality of a good or service on an invoice so as to shift capital illicitly across borders, according to GFI.

The three Association of Southeast Nations members in GFI’s top 20 list are Malaysia, ranked third with an average illicit financial flow of $39.5 billion; Indonesia, eighth, $18.8 billion; and Thailand, ninth, $17.2 billion. Brunei Darussalam placed 21st in the list of largest exporters of illegal capital with an average flow of $4.3 billion.

The report, titled “Illicit Financial Flows from Developing Countries: 2003-2012,” said crime, corruption and tax evasion, among other causes, drained developing countries of a record $991.2 billion in 2012 alone.

The study said illegal capital flowing out of 151 countries between 2003 and 2012 totaled $6.6 trillion, growing at 9.4 percent a year, roughly double global GDP growth over the same period.

Illicit outflows were even greater than the combined total of foreign direct investment (FDI) and net official development assistance (ODA) developing countries got in 2012, GFI said. They were about 1.3 times the $789.4 billion in total FDI and 11.1 times the $89.7 billion in ODA.

Governance issues and corruption have been pinpointed as a major driver of illicit flows.

“In case studies on Brazil, the Philippines, and Russia, GFI found that the link between purely illicit flows and governance tends to be even stronger than the link between capital flight and governance,” the report said.

“(I)llicit financial flows are the most damaging economic problem plaguing the world’s developing and emerging economies,” said GFI president Raymond Baker. “It is simply impossible to achieve sustainable global development unless world leaders agree to address this issue head-on.”

Joseph Spanjers, one of the two authors of the report, said: “(A) trillion dollars … could have been invested in local businesses, healthcare, education, or infrastructure. This is a trillion dollars that could have contributed to inclusive economic growth, legitimate private-sector job creation, and sound public budgets.”

According to GFI, Asia continues to experience the greatest volume of illicit financial flows, making up 40.3 percent of the world total over the 10 years covered by the study.

The trend was driven by China, which has topped the list of exporters of illegal capital for nine of 10 years. Illicit money leaving China jumped from $162.8 billion in 2011 to $249.6 billion in 2012.

India also contributed significantly to the illicit flows. It ranked fourth in the study with an average flow of almost $44 billion from 2003 to 2012.

The report identified fraudulent misinvoicing of trade transactions as an acute problem responsible for 77.8 percent of all illicit flows around the world.

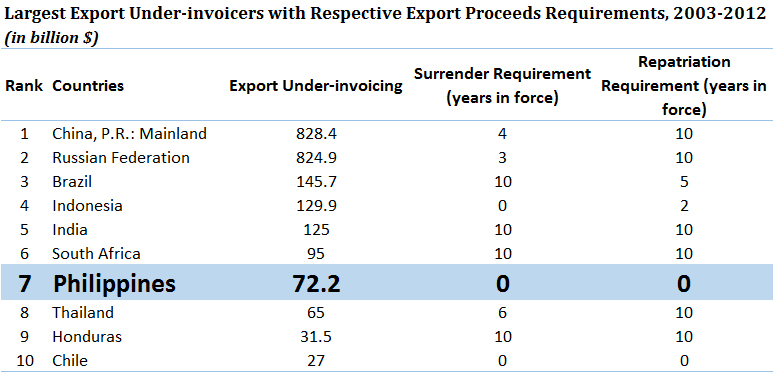

The Philippines recorded a total of $77.8 billion of trade misinvoicing outflows from 2003 to 2012, including $72.2 billion from export under-invoicing, placing it seventh among the largest export under-invoicers, the report showed.

The Philippines recorded a total of $77.8 billion of trade misinvoicing outflows from 2003 to 2012, including $72.2 billion from export under-invoicing, placing it seventh among the largest export under-invoicers, the report showed.

Likewise, it experienced outflows of illicit hot money, or leakages in the balance of payment, adding up to $15.7 billion for that period.

“Trade misinvoicing is possible due to the fact that trading partners write their own trade documents. Usually, through export under-invoicing and import over-invoicing, corrupt government officials, criminals, and commercial tax evaders are able to easily move assets out of countries and into tax havens, anonymous companies, and secret bank accounts,” GFI said.

Besides corruption and governance issues, regulatory and fiscal issues are “potential drivers” of trade misinvoicing, according to the report.

For example, exporters are known to under-invoice their goods as a way to dodge restrictive export proceeds requirements, including surrender and repatriation requirements, it said.

The surrender requirement compels exporters to surrender a significant portion of their export proceeds to the central bank or authorized dealers within a specified time period. The government may also specify the foreign exchange rate.

The repatriation requirement makes it illegal for exporters to hold export proceeds in an external account beyond the time permitted under the regulation.

GFI attributed import over-invoicing to, among others, foreign exchange regulations that allow the importer to receive foreign exchange from the government at a favorable rate for certain “essential” imports, which enables the importer to turn around and sell the excess currency in the black market for a profit.

Government subsidies, on the other hand, encourage over-invoicing of exports, it said.

Spanjers and co-author Dev Kar described their estimates of illicit financial flows as “extremely conservative.” These were based on discrepancies in balance of payments data and direction of trade statistics as reported to the International Monetary Fund.

The authors said their methodology cannot detect same-invoice faking, misinvoicing of trade in services and intangibles, “hawala” transactions (transferring money without actually moving it and without promissory notes), and dealings conducted in bulk cash.

“As they are typically intended to be hidden, some forms of illicit financial flows are difficult to estimate with precision. Many illicit transactions are carried out in cash, in order to avoid a paper (or data) trail, and are consequently not captured in government statistics,” they said.

Spanjers and Kar added, “This means that many forms of abusive transfer pricing by multinational corporations as well as much of the proceeds of drug trafficking, human smuggling, and other criminal activities, which are often settled in cash, are not included in these estimates.”

The authors called on countries to immediately address trade misinvoicing to curtail illicit financial flows through this method by at least 50 percent by 2030.

The report urged the United Nations to include a specific target next year to halve all trade-related illicit flows by 2030 as part of post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda.

It also recommended:

- Governments should significantly boost their customs enforcement, by equipping and training officers to better detect intentional misinvoicing of trade transactions.

- Governments should establish public registries of meaningful beneficial ownership information on all legal entities.

- Financial regulators should require that all banks in their country know the true beneficial owner(s) of any account opened in their financial institution.

- Government authorities should adopt and fully implement all of the Financial Action Task Force’s (FATF) anti-money laundering recommendations.

- Regulators and law enforcement authorities should ensure that all the anti-money laundering regulations, which are already on the books, are strongly enforced.

- Policymakers should require multinational companies to publicly disclose their revenues, profits, losses, sales, taxes paid, subsidiaries and staff levels on a country-by-country basis.

- All countries should actively participate in the worldwide movement toward the automatic exchange of tax information as endorsed by the OECD and the G20.

- Trade transactions involving tax haven jurisdictions should be treated with the highest level of scrutiny by customs, tax, and law enforcement officials.