BY JAKE SORIANO

EVEN before its title credits appear, the film #Y directed by Gino Santos has already told its audience its lead character is dead.

EVEN before its title credits appear, the film #Y directed by Gino Santos has already told its audience its lead character is dead.

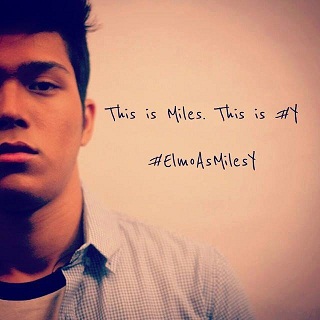

It is in fact the dead man Miles – dead boy rather, played brilliantly by Elmo Magalona who does the telling. A la William Holden in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, he relates the events leading up to his death.

Any suicide is bound to elicit the big “Why?” and Santos takes up the task to attempt and find an answer. To do this, he plays shrink, both in the film and through the film.

The challenge for Santos is to transform Miles’ interior life to what can be physically seen and visually represented. Some of the film’s visual clues lean toward the obvious (imagined scenarios, a toy brain hanging by the bed, a shirt that says “Bad decisions”) but some do open tiny windows to his worldview, for example, tiny furniture in Miles’ bedroom, or the restrictive disproportion of his bed to his size.

Clues suggesting smallness and restrictions do help the film map Miles’ emotional landscape. He has very few close friends, only three in fact, and this small circle is itself restrictive: Miles is romantically attracted to Lia (Sophie Albert) but cannot act on this attraction because Lia is already dating Ping (Kit Thompson), his best friend. His parents are okay and are responsive but only when they need to be. He could be the smartest kid in his class, if only he could find the courage to raise his hand, speak up and recite lines from The Catcher in the Rye by heart.

The central thesis of #Y, which recognizes the usual clinical (Miles has been diagnosed with schizophrenia) or cultural factors but go beyond these, is exactly that Miles’ self-destructive impulses might be rooted in his inability to arrange events in his life in any meaningful order.

Miles is someone who has lost a sense of narrative: his birth is his death. The overall architecture of the film, the beginning prefiguring the end and the end circling back to the beginning, mirrors Miles’ appreciation of living and dying. He makes sense of his life only in beginnings and endings, and since the beginning is over, there is only the end.

The poignancy of what could be a shared life-affirming moment between him and a suicide hotline employee (Chynna Ortaleza) is lost to him. He interprets it through the lenses of his bleak view of living, his firm belief that life is nasty, brutish and short.

This sets him apart from his friends, who may suffer from the same inability to create narratives out of their lives, but who are fine with ambivalence in almost everything, from religion (Coleen Garcia’s Janna says Catholicism works for her for now because she has not found her religion yet) to sex and drugs.

The film tells his story, along with the stories of his friends, and allows him a way to articulate the logic to his view of the world.

There is logic in suicide, #Y seems to be saying. There is an answer to the “Why,” no matter how fragmented and disjointed. What unsettles the living, those who are left behind, is not being able to fit the pieces back together.

“#Y” is currently screening in CPP and in select theaters in Metro Manila as part of this year’s Cinemalaya Film Festival. Schedule of screenings may be found at the Cinemalaya website.