By YOLANDA L. PUNSALAN

THIS is one most meaningful fashion statement from Sen. Loren Legarda.

THIS is one most meaningful fashion statement from Sen. Loren Legarda.

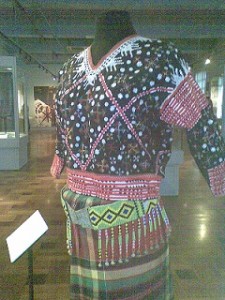

The National Museum recently inaugurated two of its permanent textile galleries enhanced by loans from the collection of Senator Loren Legarda, chair of the Senate Committee on Cultural Communities.

The traditional textiles featured in the “Hibla ng Lahing Pilipino Textile Galleries” show textiles’ central role in uniting Filipinos through common threads, weaving skills, technology and meaning to their lives.

Despite distances of the known weaving centers from northern Philippines (Ilocos and the Cordilleras) to southern Philippines (Bagobos, Mandayas and the Bilaans), there seems to be interlocking designs, themes, and leitmotifs.

“It is our duty to our people to preserve the past so that they can learn from it and instill a sense of pride,” Legarda said.

The exhibition’s smaller gallery houses three types of looms—the foot and pedal looms, normally used in Western Visayas and Northern Luzon (the ones on display are from la Union and Vigan); and the backstrap loom, used by the weavers of the Cordilleras and Southern Mindanao.

A male weaver from La Union at the exhibition’s inauguration displayed his skill using the foot loom, which is wider and can produce more complicated patterns. “I can finish a hand towel in 45 minutes and sell it at P100,” he said.

A spinning wheel for the Maranao royalty is encased in glass at the center of the gallery, implying that their tribe is the more advanced in producing fabric.

A spinning wheel for the Maranao royalty is encased in glass at the center of the gallery, implying that their tribe is the more advanced in producing fabric.

Even without exposure to fashion magazines, our ancestors exhibited an innate gift for embellishment. Most textiles burst with minute renderings of designs from nature, each pregnant with symbolism.

Dominant in the Ilocos designs are the “sinankusikos” (whirlwind) and “sinanbitwin” (constellation star). Ilocos blankets and masts normally have the whirlwind motif as their way to soothe the powers of the wind god.

Banana blankets in the Cordilleras are woven with lizard motifs because of their belief that lizards are the messengers in the spirit world watching over them.

Other common designs are the sarimanok, plaid (for malongs), zigzags, frogs, crustaceans, geometrics, zoomorphics, botanicals, celestial forms, parts of the human body and a person inside the house.

The rhapsody of colors of the antique textiles is derived from various plants such as the duhat or lumboy, mangroves, ginger, abaca fiber for white, k’nalum tree for black, and sikarig roots for red.

Each fabric is a palette for the weaver’s imagination, although the colors usually have meanings. For instance, the color red is meant for the returning warrior; yellow is for royalty; while black is the more honorable color among headhunters for it means that the warrior has killed at least 25 men.

Tribes which have no history of weaving, such as the Badjaos and the nomadic Dumagats of Aurora, simply purchase the cloths and adorn them with embroidery for their self-expression and identity.

The most embellished group seems to be the Gaddangs of Northern Philippines. They indicate their social status by donning all ornaments made of semi-precious stones and glass.

Although the textiles in the galleries reflect wealth and worn by royalty and the warrior class, they were also spun, woven and dyed for life’s myriad activities of the commoners.

For instance, baby slings are for the infants, loincloths and waistcloths from the bark of balete trees are for the Negritos of Zambales, the Manobos, men of Polillo Island in Quezon, Camarines and Cagayan.

There are knapsacks for traveling, bed sheets, blankets, men’s trousers and headdresses, and women’s elegant upper garments and malongs.

There are knapsacks for traveling, bed sheets, blankets, men’s trousers and headdresses, and women’s elegant upper garments and malongs.

The use of specific textiles also signifies milestones. Dr. Ana Maria Theresa Labrador, curator of the exhibition and who lived with the Bontok of the central Cordilleras for 14 months while doing her dissertation research, affirmed, “funeral garments enshroud the traditional highest ranking members of the community, a loose waistcloth of fine cotton gauze, with another cloth covering the corpse while it is buried in its carved coffin.” They begin to collect these mortuary textiles when their first grandchild is born.

Legarda said, “We have to support our culture bearers so they do not give up their crafts and instead encourage them to pass on their skills to the next generation.”

To enable indigenous weavers to continue their unique artistic industry, she said there should be a parallel awareness of the propagation and cultivation of the trees and plants from which the threads are spun.

Education Secretary Armin Luistro said a Mindoro weaver told him they have not gone back to weaving in Mindoro (because) there are no more ‘kapok’ trees in the area.

On her own initiative, fashion designer Patis Tesoro has cultivated pineapple bromeliads in Panay that became her constant source of pina cloth for her creations.