“I will protect you. I will not allow one policeman or one military to go to jail; I will pardon 10, 15 military and policemen everyday” (Rodrigo Duterte, July 17, 2016, September 2016).

“Shoot them dead. Understand? Dead.” (Rodrigo Duterte, April 1, 2020).

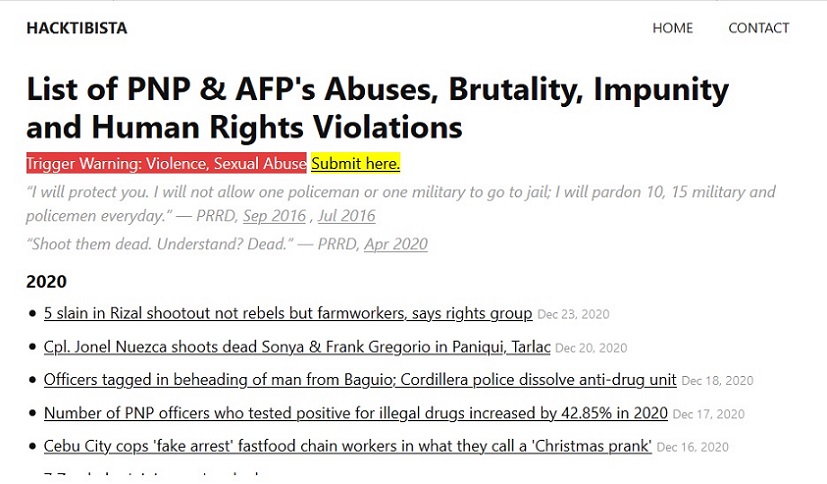

So goes the prelude in the website Hacktibista, which keeps a running list of police and military brutalities. It is naïve to believe that these volatile policy declarations of Rodrigo Duterte have not reached the attention of the International Criminal Court (ICC).

The list is updated regularly. It includes policeman Jonel Nuezca’s cold-blooded murder of Sonya and Frank Gregorio in Tarlac on December 20, 2020. Likewise, there are conscious citizens that have taken note of police infractions on New Year’s Eve.

Police Staff Sargent Karen Borromeo of Malabon city was arrested after her neighbors reported gunfire from her home just prior to midnight. It turned out she had discharged her firearm that, like Nuezca’s, was also issued by the Philippine National Police and fired off-duty. Duterte had ordered the PNP to do away with gun muzzle sealing, which previous presidents had enforced.

Have neighborhood citizens attained the much-needed boldness to report police abuse after seeing Nuezca fire his gun on Sonya Gregorio’s head as casually as a Tokhang hitman would? The on-the-spot video went viral, and we owe anyone who or any group that keeps tabs of police and military killings for widespread public consciousness at a time of government-sanctioned impunity. Only that kind of boldness matches Debold Sinas’s wet blanket to mobile videos recording police killings.

In lightning-fast speed, government apologists evaded any act of contrition for the Nuezca murders by using what is by now their operative word: isolated. Hacktibista’s list tells us these are far from isolated.

The list is sourced from mainstream media, none of which, by the way, have been red-tagged by McCarthyist medievals Antonio Parlade and Lorraine Badoy. In relying on mainstream media reportage, it will disappoint those who cry fake news because it can easily pass the muster of fact checkers. It began in 2016, and has so far recorded major cases of police and military perpetuated crimes, abuses, and overkill. It also records Duterte’s violent and misogynistic rhetoric.

Since the Nuezca murders, the list has been updated to include the murder of five farm workers in upland Baras, Rizal. A neighbor who had known the fatalities attested surprise because she had seen neither firearms nor cell phones in the three years she had frequented the house by the brook where the community often gathered to wash laundry. However, the military has fallen back on the standard but discredited narrative of police killings: the victims fought back.

Hacktibista’s December 2020 list is quite lengthy. Certainly, it did not miss one of the most gruesome murders committed in the hands of police. In November, the headless body of a 25-year-old Baguio city resident was found in Benguet province. Two police officers of the Cordillera regional police were identified and suspected by the Baguio city police chief for the crime. Yet regional police chief R’Win Pagkalinawan invoked the operative mantra: “It was an isolated incident.”

Isolated cases may be driven by operational lapses (unintended mistakes) or by rare displays of human passion (police are trained to develop tolerance). But the biggest evidence these are institutionally sanctioned is the introduction of the police jargon “Homicide Under Investigation.” In fact, the Tokhang killings have continued but are mostly unrecorded because of the HUI classification, effectively and superficially stopping the rise of figures. That is the reason the total remains at an incredible number of less than 10,000.

Government apologists are better reminded that where even brazen killing has taken place within institutional confines, “isolated” hardly describes police audacity and capacity for brutality. This is best exemplified by the murder of the Korean national Jee Ick-Joo that, to the chagrin of police, has been added to Wikipedia, the world’s virtual encyclopedia, for posterity. Jee was kidnapped and strangled right inside Camp Crame by the state’s own forces tasked to “serve and protect” during the tenure of Bato dela Rosa, who is named in the complaints for mass murder in the ICC.

One such “isolated” case can be as preposterous as the San Juan del Monte passersby incident. On Valentine’s Day 2020, “policemen of San Jose Del Monte, Bulacan, kidnapped passersby, made them out to be drug suspects, killed them in separate instances, and faked stories of nanlaban (fighting back), according to the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI).” The six killed were not even in any drug watch list. NBI chemistry reports revealed all tested negative for powder burns.

Calling the killing in cold blood of Dr. Mary Rose Sancelan, a local government inter-agency task force community doctor, and her husband – simply on the basis of a hit list by an “anticommunist vigilante group” whose cowardly members are faceless and nameless – “isolated” hardly soothes the confidence of ordinary citizenry. In the Sancelan case, it appears to be a smokescreen because the military may know who the killers are.

State actors cannot feign the collective idiocy of the watching public. “Isolated” does not apply when there are patterns of killings. Precisely because they recur and replicate, the gravity threshold of such killings is sufficiently high because of their cumulative number. “Isolated” should be understood in no other way but as a conceptual oxymoron designed to hide the fact: there is deliberate orchestration to give state forces a license to kill that, at the same time, is open to police and military abuse. Just watch out for the next “isolated” case because it will be sooner than later.

The views in this column are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of VERA Files.