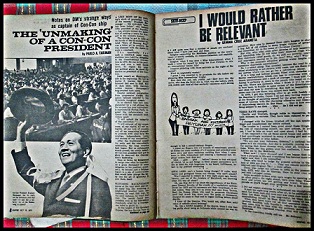

By PABLO A. TARIMAN

AS the country recalls a dark chapter in its history by marking the 40th anniversary of martial law, it is interesting to note how that event actually changed people’s lives, most of them media icons.

AS the country recalls a dark chapter in its history by marking the 40th anniversary of martial law, it is interesting to note how that event actually changed people’s lives, most of them media icons.

In his book, “Chino” which is about the owner and publisher of Manila Times, Joaquin “Chino” Roces, author Vergel O. Santos, referred to the imposition of martial law in the chapter entitled “A Thief in The Night.”

He noted that former President Marcos visited Roces a week before September 21, 1972 and intimated his plan to impose martial law. Roces, told his eminent visitor in clear terms, he would resist it.

On the week martial law was declared, a bus bound for Camp Bonifacio carried the following media persons and oppositionists: Roces, Ninoy Aquino, Teodoro Locsin, Sr. Napoleon Rama, Jose Diokno, Francisco Rodrigo, Ramon Mitra, Jr., Max Soliven and Jose Mari Velez, among others.

In the case of writer-journalist Carmen Guerrero Nakpil who used to work with the Manila Times, she thought her close kin would be spared because Marcos was a San Juan neighbor of long standing and genuinely preferred him to Diosdado Macapagal during the 1965 elections.

In her autobiographical book, “Legends and Adventures,” Nakpil wrote that particular presidential elections rattled the domestic peace in her San Juan household. Her husband, Angel Nakpil, preferred Macapagal and she preferred Marcos. During that presidential campaign, her husband’s Benz carried Macapagal stickers and her little Renault was “plastered with Marcos’ exuberant promises.”

In her autobiographical book, “Legends and Adventures,” Nakpil wrote that particular presidential elections rattled the domestic peace in her San Juan household. Her husband, Angel Nakpil, preferred Macapagal and she preferred Marcos. During that presidential campaign, her husband’s Benz carried Macapagal stickers and her little Renault was “plastered with Marcos’ exuberant promises.”

Years after martial law was declared, Nakpil got it from the former First Lady Imelda Marcos that she was in the list of those about to be arrested but the latter vouched for her and her name was removed from the prominent Martial Law prisoners’ list.

She actually got an advance notice of the imposition of Martial Law from writer Adrian Cristobal who was then head of the Social Security System. A day later, her nephew, Amadis Ma. Guerrero, then writing for Graphic Magazine and Associated Press, was at her doorstep looking for a place to hide, followed by Nick Joaquin with Pete Lacaba in tow.

Then she remembered her celebrated activist-beauty queen daughter, Gemma Cruz then married to Antonio (Tonypet) Araneta. At that time, the former Miss International was a member of Makibaka, a militant women’s movement that she sensed was more leftist than feminist. As part of her Makibaka work, Gemma helped take care of a day care center for the families of market vendors in San Andres Bukid.

Nakpil inspected Gemma’s boxes in the family library and found them full of anti-Marcos propaganda. She asked her maid to dump those boxes in the nearby creek.

As it turned out, it was Gemma’s turn to be invited by the military. The former Miss International was interrogated for almost a week and later put under city arrest and was told to report regularly at Camp Aguinaldo.

After months in hiding, Gemma’s husband, Tonypet, was also arrested while visiting his family in Forbes Park and incarcerated in Fort Bonifacio.

After months in hiding, Gemma’s husband, Tonypet, was also arrested while visiting his family in Forbes Park and incarcerated in Fort Bonifacio.

At that time, foremost in Nakpil’s disposition was her mother’s instinct. She couldn’t imagine her daughter in jail so did her son-in-law. Swallowing her writer’s pride, Mrs. Nakpil personally saw Marcos and implored that her son-in-law be released. The family decided it was better if they leave the country. Gemma flew to Canada and ended up in Mexico with her daughter Fatimah while her son, Leon (then only three years old), was left in his father’s care in Manila.

In Nakpil’s own words, the family was shattered and the marriage never recovered.

Nakpil described teh effects of Martial Law on her family: “On our family, it caused pivotal, grievous, collateral damage. It wasn’t only the truncation of my journalistic work, but also the hyper-real destruction of a family, and great personal tribulations and sacrifices.”

For sparing her daughter and son-in-law from prolonged harm of martial law, Nakpil couldn’t say “No” to a Marcos job offer.

She was aware people were asking questions as to why she worked for the Marcoses.

Nakpil rued: “My reply would usually be a forthright soliloquy. It isn’t really, just that I compromised myself by pleading for clemency and freedom for my activist daughter and son-in-law, or that I like the projects in the Technology Resource center where I work, but also at bottom, because Marcos was doing important things that I swear by… I found comfort in reminding myself that I was a dutiful bureaucrat, well-intentioned, but destined by circumstance to be caught in the maelstrom.”