The sea turtle, commonly known as pawikan in the Philippines, is an endangered marine animal yet it continues to be harvested and slaughtered for its meat, eggs and shell, which are sometimes openly sold, proof that humans pose a serious threat to its existence.

Dr. Rizza Salinas, veterinarian in the Biodiversity Management Bureau (BMB) under the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), says that while climate change can reduce food supply of animals, the main reason the population of marine species is under peril is mostly anthropogenic or man-made.

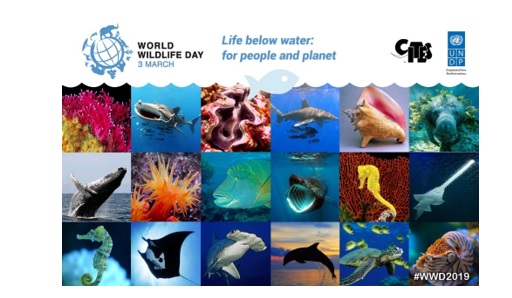

As countries observe World Wildlife Day on March 3 with the theme, “Life below water: for people and planet,” conservationists call for increased public awareness of the need to protect the endangered marine animals.

Of the five species of marine turtles in the Philippines, four are considered endangered and one — the hawksbill — is critically endangered. Their collection and trade are prohibited by law.

Rows of sea turtles or Pawikans. Photo from DENR – Biodiversity Management Bureau Facebook Page.

The pawikan has a ‘high economic value,’ according to Salinas, which means many would want a sea turtle.

“Just outside the Philippines, many already want to catch pawikans. They would lay nets from island to island just to catch a sea turtle,” she said in Filipino.

Salinas says sometimes people get hold of turtles only to take their scales, which are used for decoration and accessories, then release them back into sea.

“After they get (the scales), they return the pawikan to the sea, believing they will still live. They think if they still breathe, the scales of the pawikan will grow back.”

But they do not. Most of the time, the pawikan are left to die unprotected in the ocean, she said.

Though the sea turtle is a protected animal, Salinas claims traders sell the pawikan from house to house to avoid detection and arrest. However, others openly sell them in the market, and hide the turtles and their eggs when they see the police coming.

The flesh of the sea turtle, including its head and flippers, can be made into cured meat, and also an ingredient in preparing soup.

Beyond its value as food, the presence of a Pawikan in a household also indicates a high social status, Salinas adds.

“It is a status symbol outside the Philippines. If you display a stuffed pawikan, it means you’re rich, you’re at the top of society in other countries. That is why many want sea turtles.”

Habitat destruction

Another popular endangered local marine creature is the sea cow, also known as dugong.

“When it comes to the dugongs, their main threat here in the Philippines is really habitat destruction,” Salinas explains. “What comes from the river goes to the sea. You can see former sea grass beds filled with mire, so dugongs run out of edible food, so they leave the area.”

Other than the lack of a stable area for food supply, dugongs are also victims of collateral, man-made damage.

“Some people think if they use dynamite fishing to catch fish, no one else is affected. It doesn’t cross their mind that once they throw the dynamite, it can hit the dugong. We encountered that.”

Salinas adds: “In the Philippines, no one deliberately catches a dugong to eat it. Although in rare occurrences, if there is a stranded and very weak dugong, that’s when they’ll only think of dismembering it.”

A

sea cow or Dugong. Photo by Dr. Helene Marsh. Source: Biodiversity Management

Bureau

Key to conserving these endangered animals is addressing the threats and the BMB’s flagship program, the Coastal and Marine Ecosystems Management Program (CMEMP), is trying to do just that.

The BMB also ties up with local government units (LGUs) to provide alternative livelihoods for communities that rely on marine animals for their food and income.

Giving emphasis to anthropogenic reasons as the main culprit for marine life peril, the CMEMP aims to “comprehensively manage, address and effectively reduce the drivers and threats of degradation of the coastal and marine ecosystems,” the BMB says in its website.

“The approach should be from ridge to reef, from uplands to lowlands, because it is where human settlements are that highly impact marine ecosystems,” said BMB Environment Management Specialist James Santiago.

“The usual livelihood here in the Philippines is extractive, so we heavily depend on natural resources, but we are promoting alternative livelihoods so that we promote biodiversity conservation,” he said.

Promoting sustainable tourism is one. “We don’t do any extracting. It gives livelihood to coastal communities, as compared to only eating it, it will only be utilized once. If we’re going to use that organism for sustainable tourism, the benefit is continuous. Also, you get to appreciate the beauty of nature.”

‘More reports, better results’

Salinas claims there has been a big improvement over the years. Parallel to the increase of sea turtles is the increase in awareness and response to the vulnerability of the creatures.

“More people now report, not just the illegal activities, but also sightings of pawikan or dugong somewhere. In the recent years, at least, they learned to report them to the DENR.”

“The number of Pawikans is increasing. Even the number of released hatchlings is increasing because they know now how to protect the nest,” she added.

Both non-government organizations and private groups are involving themselves in the conservation of the marine animals.

Just last January, the Aboitiz Group, a hydroelectric power generation company, built a Pawikan Center in Davao for the conservation of sea turtles, which includes the critically endangered hawksbill sea turtle.

Even beach resorts coordinate with the BMB on conservation efforts.

“We have beach resorts like El Nido constantly communicating with us. If they see a pawikan, they know what to do. If they don’t know what to do, they will call the BMB,” Salinas said.

In Palawan, she relates, there is an NGO that encourages mothers in the community to make small dugong key chains which they sell, and male fisher folk are trained as tour guides. They still fish but do not resort to illegal fishing activities.

For marine life advocate group, Marine Wildlife Watch Philippines (MWWP) Director AA Yaptinchay, the endangerment of species still needs attention.

“Awareness is important,” he said, adding that the implementing agency should also help in educating the public.

Asked how endangered marine species could fare in the future, he said: “Most of them are protected already in the Philippines – either by the Wildlife Act or by the Fisheries Code.” But the same cannot be said for sharks.

The Wildlife Resources Conservation and Protection Act (RA 9147) aims to conserve the nation’s wildlife resources and their habitats. The Philippine Fisheries Code of 1998 (RA 8550) aims to manage and conserve fisheries and aquatic resources.

“For the sharks, only 19 species are protected,” Yaptinchay said. “We are trying to address the gap. That’s why there’s a Shark Bill because there are 200 species of sharks, so why are only 19 protected?”

Just last month, the House of Representatives approved on second reading House Bill No. 8926 or the proposed “Shark Conservation Act of the Philippines” which seeks to regulate the catching, sale, purchase, possession, transportation, importation, and exportation of all sharks, rays, and chimaeras in the country.

Government and community efforts

For Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) National Director Eduardo Gongona, to address the diminishing number of fish production, the municipal waters should be monitored carefully by government agencies aligned with environment, fisheries and maritime.

These include the navy, police, coast guard, Customs, Bureau of Fisheries, BMB, Environmental Management Bureau, the LGUs and others.

“They need to monitor the municipal waters to improve fish production. By doing so, they also improve their mandate because they can now watch over where much of what is illegal – drug trafficking, human trafficking, smuggling, piracy, terrorism – comes from. Almost all use the sea,” Gongona explained.

The BFAR initiated a program entitled Malinis at Masaganang Karagatan (MMK) (Clean and Abundant Seas): search for the country’s most outstanding coastal community where communities can win as much as P30-million if they continue legal fishing practices and keeping their coastal community clean and abundant with mangroves.

“We need to balance enforcement and productivity. You will produce more if you enforce more properly the laws,” the director added.

This story is produced by VERA Files under a project supported by the Internews’ Earth Journalism Network, which aims to empower journalists from developing countries to cover the environment more effectively.