“Do not cry, Pepito. Show these people that you’re brave. It’s a rare opportunity for me to die for our country. Not everyone is given that chance.”

— Jose Abad Santos to his son

Jose Abad Santos is a Filipino hero who comes to mind among a few during National Heroes’ Day. But even if I recalled his name and his portrait at Jose Abad Santos Memorial School (JASMS) in Quezon City, which I attended from grade school to high school, my knowledge of him was limited and incorrect.

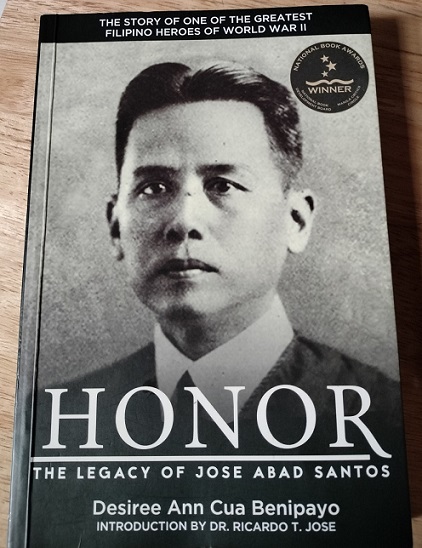

When I was a student at the school named after him, honoring his memory meant always hearing the story of how the late former chief justice and justice secretary was captured and supposedly beheaded by Japanese occupation forces. The circumstances of his death were some of the details I learned decades later in reading “Honor: The Legacy of Jose Abad Santos” published by Philippine World War II Memorial Foundation Inc. and written by Desiree Ann Cua Benipayo.

In the book, Benipayo corrected the misinformation. She wrote that Abad Santos was shot dead under a tall coconut tree near a riverbank shortly after telling his son Pepito to be good and to take care of their family. He was escorted by seven soldiers to a coconut grove at the turn of a road in Malabang, Lanao del Sur.

My learning about Abad Santos was long overdue, and reading “Honor” meant reaching an understanding of the man in whose honor my alma mater was – a hero of courage, dignity and altruism who believed that extending help to others without ulterior motives should be the norm and not the exception.

Calm under fire

Abad Santos was executed under shady circumstances. Per Benipayo, the trial later held to find out why Abad Santos was killed revealed his execution as a clandestine operation orchestrated by Maj. Gen. Yoshihide Hayashi. It was not ordered by Gen. Masaharu Homma, the commander of the Japanese 14th Army believed to have masterminded it.

Abad Santos walked to the execution ground tranquil like Rizal, refusing the blindfold and cigarette offered to him by members of the firing squad, Benipayo narrated, quoting Keiji Fukui, the London-educated interpreter who stayed with Abad Santos.

Gen. Kiyotake Kawaguchi, head of the Japanese forces that landed in Cebu, expressed the same sentiment. He said Abad Santos was dignified during interrogation and calm when told of his imminent execution. Responding to Kawaguchi, Abad Santos said he wasn’t anti-Japanese and thanked the general for sparing his son’s life. The order had called for the execution of father and son; Kawaguchi carried out the execution of the father only.

Kawaguchi’s testimony at the trial in 1949 showed reverence for Abad Santos: “I’d never seen a man act as greatly as he did…Death is a serious thing to human beings, but he acted calmly as if he were just going home.” Significantly, Kawaguchi opposed Abad Santos’ execution and wrote to the top brass to stay the order. Failing to save Abad Santos and aided by Fukui, he safeguarded the son, who was taken to Tokyo as a prisoner of war.

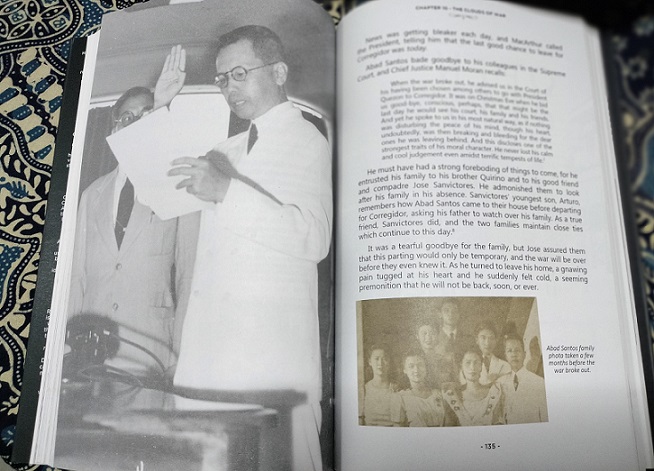

Abad Santos could have avoided his grim fate if he had gone with President Manuel L. Quezon to Australia, the site of the government-in-exile. He declined, reasoning it was his duty to stay and share his compatriots’ suffering and hardship, wrote Benipayo. Quezon left him in charge, with full presidential powers.

He was captured by the Japanese and subjected to difficult interrogation. Learning that they had captured the head of the country, the Japanese wanted him to serve in their new government, Benipayo wrote.

Abad Santos rejected the idea, saying: “To obey your command is tantamount to being a traitor. I would rather die than live in shame!”

All in the family

Abad Santos was a chip off the old block, “quiet, diligent, determined, and scholarly” like his father Don Vicente who inculcated in all his 10 children the importance of a just society, wrote Benipayo.

The tragedies his family endured because they believed in social justice and equality toughened Abad Santos. He remained self-sacrificing throughout his life.

Don Vicente was charged with conspiring against the Spaniards, and died after being beaten and tortured. With his arms bound behind him and his feet tied together, he was dragged by a horse from San Fernando to Bacolor in Pampanga for the public to see, wrote Benipayo.

His older brother Pedro was imprisoned on suspicion of being a member of the revolutionary society Katipunan, but was released with the help of influential friends. Pedro Abad Santos was later arrested by the Americans and charged with “guerrilla activities and allied crimes.” He was meted out a death sentence — which was eventually reduced to 25-year imprisonment in Guam — because he refused to swear allegiance to America.

Bikong del Rosario, Abad Santos’ brother-in-law who was captured by the Americans, was hanged for killing an abusive American soldier. Del Rosario and Pedro Abad Santos also joined the fight against the Americans.

Citizens’ defender

Abad Santos — nicknamed “Sengseng” — was a courier for the Katipunan at 10 years old, and resumed delivering messages two years later, “crossing American lines…to and from San Fernando, Angeles, and Mabalacat,” wrote Benipayo.

His dedication never faltered. In an argument with his mother, he told her he didn’t care if the Americans jailed him because he was “helping in [the] country’s fight for freedom.”

In 1904, Abad Santos went to the United States as a Filipino scholar (pensionado). He graduated with a bachelor’s degree in law from Northwestern University and a master’s degree in law from George Washington University.

Benipayo theorized that Abad Santos was moved to pursue law and protect Filipinos’ rights because of his experience of standing by helplessly as his brother Pedro was arrested for defending his country and of seeing the poor conditions of freedom fighters. Years later, he would champion women’s rights including the right to education. He drafted the bylaws and constitution of the Philippine Women’s University where he, in 1924, became the chair of the board of trustees, working pro bono until the onset of World War II.

Incorruptible

That Abad Santos’ government service record was free of scandal and corruption throughout his career underscored his lofty principles and moral integrity, asserted Benipayo. In his life, he showed Filipinos that a public servant must have commitment, integrity, and, not the least, intelligence.

He first worked as assistant attorney at the Bureau of Justice, where his superiors, particularly Attorney General Ramon Avanceña, impressed upon him the significance of upholding one’s convictions. He witnessed how Avanceña, who didn’t kowtow to politicians, got his office budget cancelled and was demoted to judge of the Court of the First Instance of Manila when he didn’t play nice, said Benipayo.

Abad Santos held the post of justice secretary thrice. In 1922-1923, he and Governor General Leonard Wood dismantled the palakasan system (using connections to get a job, etc.), “regained people’s trust and confidence,” and restored efficiency, honesty, and competence in government service, said Benipayo.

In 1928-1932, Abad Santos took on the herculean task of rebuilding the justice system. He wanted to improve the courts and regain the people’s trust in them. He encouraged judges to be worthy of the bench and firm against errant officials. He required court employees to be at their stations promptly at 8 a.m. He inspected courts and jails nationwide. He lobbied for funds to build new prison facilities in Northern Luzon and in Mindanao to decongest the existing jails. He demolished the rice cartel and looked into newspaper reports on allegations of inefficiencies in courts and judges who sentenced prisoners without a trial.

Benipayo wrote that one of his most important accomplishments was the construction of a separate prison facility for women. Female prisoners were transferred to the new women’s correctional in San Felipe Neri, Mandaluyong, on Feb. 4, 1931.

In 1938-1941, apart from being President Quezon’s legal adviser, Abad Santos managed the Bureau of Justice, all the courts except the Supreme Court, the Bureau of Prisons, the Civil Service Commission, and the Land Registration Office, said Benipayo.

His appointment as chief justice was the icing on the cake. It was equally momentous because he succeeded the retiring chief justice, his mentor Avanceña.

According to Benipayo, Abad Santos had all the qualities of a judge — intellectual ability, judicial acumen, moral integrity, and a calm, cool temperament.

In his honor

Not much is known about Abad Santos although a school is named after him.

In Pampanga where he was born in San Fernando on Feb. 19, 1886, May 7 is Jose Abad Santos Day, a nonworking holiday. (The first Jose Abad Santos Day was held on Feb. 19, 1956, in San Fernando.)

There are towns and streets that bear his name. Benipayo lists the laws enacted in this respect: Republic Act No.1206 changing the name of the municipality of Trinidad in Davao Occidental to Jose Abad Santos; RA 1256 changing the name of Manuguit Street, a national highway in Manila, to Jose Abad Santos Street; and RA 1257 changing the name of San Fernando Diversion Road in Pampanga to Jose Abad Santos Boulevard. And a 1.83-meter statue of him now stands in Malabang, Lanao del Sur.

In the surfeit of information that marks this technological age, Filipinos need to know more about this hero whose steely character and sterling accomplishments in public service leave incumbent officials eating his dust.

“Honor: The Legacy of Jose Abad Santos” is available at Popular Bookstore and Philippine World War II Memorial Foundation Inc. (FB: Philippine World War II Memorial Foundation).