Images courtesy of the Philippine Coffee Board

In celebration of International Coffee Day (Oct. 1), the Philippine Coffee Board hosted a webinar on the history of coffee in the country by Felice Prudente Sta. Maria, a noted food historian, and Pacita Juan of PCB.

Basic questions on the origin of coffee remain unanswered: Who brought coffee to the Philippines? Who planted them? Where did they come from? (And no, it was not really a Franciscan friar in Lipa).

The global beverage

Widespread in the Arabian Peninsula, drinking coffee had spread to the Islamic world and to Europe by 1536. Coffeehouses were established by the mid-17th century in Venice (1645), Oxford (1650), Paris (1672), Vienna (1683), and Hamburg (1687).

In contrast, the insular Southeast Asian region and Spain did not have any coffee growing at all, in the 1500s. The Dutch brought coffee to the Asian region and managed to grow coffee in their colonies, followed by the French.

Coffee in Asia

The Dutch governor in Malabar (India) sent a Yemeni or Arabica coffee seedling to the Dutch governor of Batavia (Jakarta) in 1696. Due to flooding, the first seedlings failed; a second shipment of seedlings was sent in 1699. The coffee plants grew in Java and in 1711, the first coffee plants from Java were sent to Amsterdam. (A History of Global Consumption: 1500-1800, 2015). Under compulsory cultivation, Java began exporting coffee to Europe in the early 18th century through the Dutch East India Company. In the 1880s, Java’s share was 18 percent of world coffee export.

By the 1700s, it was the French who were drinking coffee and made the Spanish aware of this new beverage. Sta. Maria notes that even in 19th century, the time of Jose Rizal, chocolate was the main beverage in Spain and the Philippines. It was only after the Spanish Civil war (1936-1939) or around the Philippine Commonwealth era (1936-1946) that drinking coffee became popular among the Spanish.

Questions remain

Some oft-repeated claims with regards to coffee:

A Franciscan friar brought coffee to Lipa, Batangas in 1740 or was it the Agustinians, as stated in a church plaque in Lipa; Lipa between 1886-1888, Lipa was the sole supplier of beans to the world; the coffee leaf rust ended Lipa’s coffee boom; the Philippines in 1886 was the world’s fourth largest exporter of coffee.

Most likely, the tale of the Spanish friar is apocryphal; statistics on world coffee exports in the 19th century belie such claims. A PhD dissertation by Maria Rita Castro from the University of Adelaide, 2003 debunks the above-mentioned claims, and gives a more nuanced historical context on the role of coffee in Lipa, Batangas.

Confounding researchers, no written documents, or historical sources have been uncovered that gives evidence to this Franciscan friar tale, says Sta. Maria.

Paul de la Gironière

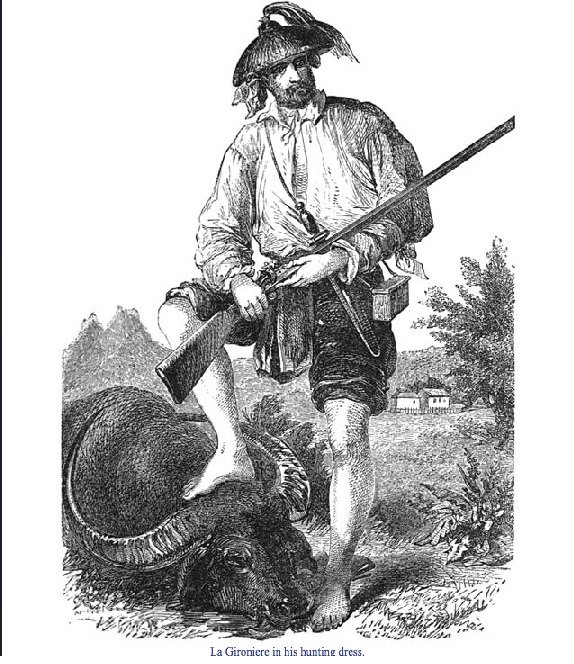

It was an agricultural pioneer ,French doctor Paul de la Gironière (1797-1862), who planted coffee, abaca, sugarcane, and rice in his 2,400-hectare estate in what is today Jalajala, Rizal. By 1837, he had raised some 6,000 coffee plants and awarded a cash prize of 1,000 pesos. He invited another Frenchman from Bourbon Island (Reunion Island), known for its coffee, to help him out.

The National Historical Institute placed a marker in 1978 on what had been Gironière’s property overlooking Talim Island. Gironière recounted his experience in a book, Twenty Years in the Philippines, 1853.

Café culture

With the opening of the country to international trade (1835) and the opening of Suez Canal, foreigners started arriving in Manila by steamship; inns and hotels were established, coffee and tea were served in these places.

By 1881, only three cafés were around: Café de la Campana in Escolta, El Suizo in Santa Cruz, and La Esperanza in Intramuros.

Under the American period, all girls in public schools taking home economics across the Philippines, were taught how to cook and how to prepare beverages—chocolate, Spanish style and American style with milk, and how to brew coffee in a pot.

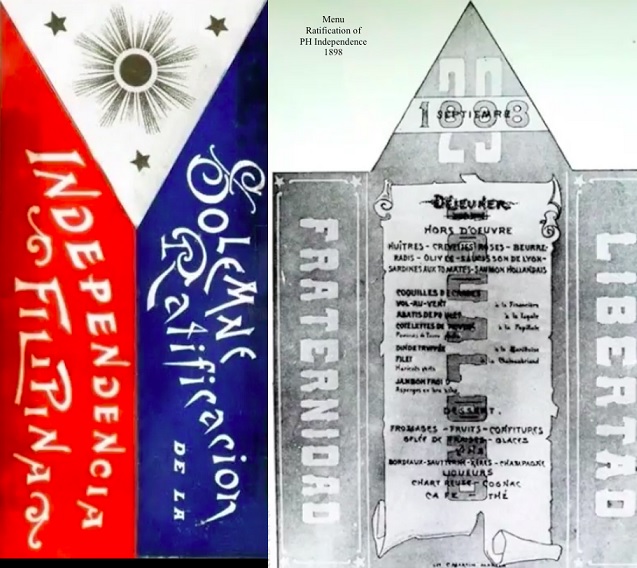

On September 1898, the menu card banquet on the ratification of Philippine independence by the Malolos Congress offered tea or coffee, a gesture that the country had embraced the habits of “Western civilization.”

Convenience

Sta. Maria emphasized that chocolate was much easier to prepare, especially in tablea form. In contrast, it was rather complicated to serve coffee. Coffee beans needed to be roasted, ground, and boiled before serving with milk and sugar. And consistency in taste was a hit-or-miss affair. So, Filipinos stuck to drinking chocolate.

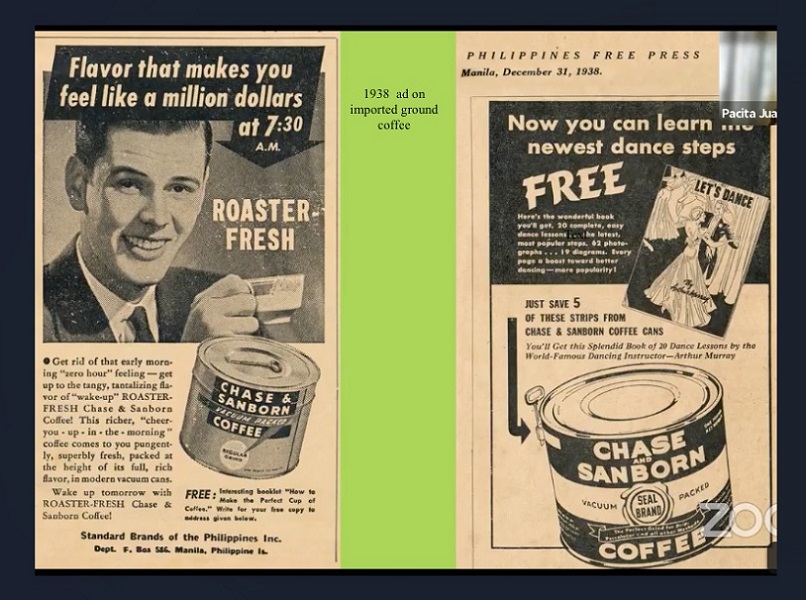

However, with imported ground coffee during the American period, drinking coffee suddenly became convenient. Initially part of the military K-ration, the advent of instant coffee solidified the appeal of convenience.

Today, DTI’s policy brief states 90 percent of coffee consumed in the Philippines is instant coffee. The Philippines’ coffee production level is quite small-scale. In 2015, Philippine exports of green and roasted coffee accounted for less than 0.0004 percent and 0.0003 percent of global trade, respectively.