By MARC JASON CAYABYAB

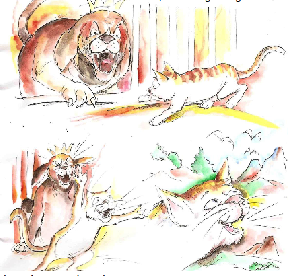

IN a kingdom of animals in Pangasinan, all were free to speak in their own sounds. But when a cruel and evil dog named Bosangel(troublesome) conquered the land, he ordered all the animals to stop using their own sounds and do what dogs do — bark.

While the rest of the animals followed, a cat named Liwawa (light) refused. Bosangel hadLiwawa imprisoned and ordered to bark. But the brave cat did what she was born to do. She meowed.

The rest of the animal kingdom heard Liwawa’s meow and followed with their own sound. The cows mooed, the carabaos bleated, the roosters crowed. Stunned by the defiant sound, Bosangel and his followers ran away from the kingdom, their tails behind their backs.

Erwin Fernandez’s children’s story entitled “Si Liwawa, say pusan agto gabay so ondangol” (Liwawa, the cat who refused to bark), is not just about animals’ struggle to assert their own identity.

It’s an allegory of the state of culture in his home province Pangasinan, where the vernacular language is under threat of extinction.

Literature, or kuritan in the vernacular, serves as their only means to keep the language alive, according to many Pangasinan writers.

Fernandez, a former history professor at the University of the Philippines, said Pangasinan’s vernacular language is in danger of being lost due to the entry of other languages in the province.

He said the threat to the language comes from the Ilokanos and more so from the Tagalogs.

“Tagalog imperialism,” as he would call it, refers to “the imposition of the national language (Tagalog, later to be called Filipino) to the detriment of other languages.”

In the 1920s, when there was no national language imposed, the UP historian recalled that Pangasinan language flourished. He said the vernacular language suffered a setback the time former president Ferdinand Marcos imposed the bilingual policy in 1974, which required Filipino and English to be mediums of instruction.

“This educational system made it impossible for the Pangasinense children to think and speak in Pangasinan,” Fernandez said.

“We have surrendered our right to our inherent language to other languages. This is the reason why there is a decline in our own culture,” he said.

Pangasinan poet Santiago Villafania does not entirely put the blame on the other languages being used in the province. He said it is the Pangasinenses who refuse to use their language and realize that its inherent beauty is something that is not to be ashamed of.

“The Pangasinan language is not dying,” the Pangasinan mangaanlong (poet) said. “What is really in trouble is the written language, but spoken (language) is very much alive.”

Villafania is also a strong advocate of the Pangasinan language and his anlongs (poems) have been translated in various languages worldwide.

“Hangga’t ginagamit natin ito (As long as the vernacular language is being used), I don’t think it would die; It doesn’t deserve to die,” poet Jesamyn Diokno said.

For Emilio Jovellanos, a lexigographer or specialist in the vernacular vocabulary, Pangasinan is no longer a “dying language.” He said the language now sees resurgence due to efforts by proud Pangasinenses to keep the language alive—that is, by writing in the vernacular.

For many vernacular writers, the language merits its literary use primarily due to the inherent beauty of the language.

Jovellanos, in his Pangasinan-English Language dictionary, likens the Pangasinan language to the French language, quoting his linguistics professor at the University of Sto. Tomas Jose Villa Panganiban.

Its rich vocabulary, especially in the adjectives, also makes it easier for the writers to produce literary works. For instance, the word “crazy” in the Pangasinan language can be translated in 15 words like atapis, atiwel, and ambagel—each with its own context.

This variety in the language makes it easier for Diokno to make her poems, as it gives her more options to express herself.

Diokno, who writes poetry based on her experiences in her homeland San Carlos City, was described by Villafania as the “Pangasinan Sappho” in reference to the female Greek lyrical poet.

While the spoken language may seem like “two people arguing,” Villafania added that the language has an inherent “lyricism” in the written word.

“Part of poetry is the musicality,” he pointed out. “May rhythm, parang song sa pandinig (The language has the rhythm of a song) without actually singing it.”

Pangasinan writers believe that it is only through literature that Pangasinenses can truly appreciate the beauty of their own language.

“It is important to read Pangasinan literature because it is the only way we can imagine ourselves as a people,” Fernandez said, adding that language is the “bearer of our culture.”

Once their own language dies, the Pangasinenses’ own culture, their own identity, will inevitably get its own death, he concluded.

It would very well take another Liwawa to keep the Pangasinan language alive. The vernacular writers are now making the first meow.

(The author is a University of the Philippines student intern of Vera Files.)