The struggles for independence of the Philippines were honored last month — the 39th anniversary of the Edsa People Power Revolution on Feb. 25 and the liberation of Manila from the Japanese on Feb. 3. The latter was commemorated by the Philippine World War II Memorial Foundation (Philwar) in a conference titled “War & Memory: 80 Years After” at Lyceum of the Philippines University on Feb. 18 and 19.

Philwar vice president Desiree Ann C. Benipayo wrote in the conference program that the Japanese occupation was “the darkest and most tragic of all.” She added: “Civil liberties were removed, private properties commandeered, and citizens tortured and killed for mere suspicions of resistance activities.”

In the same program, Regalado Trota Jose Jr., National Historical Commission of the Philippines chair, said it was important to remember events like the liberation of Manila. The American forces declared Manila a free city a month after its bombardment on Feb. 3, 1945, with the estimated death toll at 100,000 Filipino civilians, 16, 665 Japanese soldiers, and 1,101 American soldiers.

Trota aired the same sentiment in his opening remarks at the conference: “We should look at [WWII] in a new perspective and use the knowledge to work for peace and justice.”

The 36 speakers discussed the Japanese occupation and Filipino resistance to it on the first day of the conference, and the Battle of Manila and postwar problems the following day.

Japanese diet

The Japanese downplayed the scarcity of food and promoted wartime food as equal to prewar food, said Rad Xavier Sumagaysay in his paper “Nutrition, Indigeneity, and Food Substitutes in WW2.”

Japan’s food campaign publicized local food as nutritious substitutes for Western food, and declared the consumption of local food as a patriotic act. Filipinos were compelled to follow the Japanese diet of lightly cooked, single-ingredient meals, which, Sumagaysay argued, was incompatible with Filipinos’ physiology and environment.

Sumagaysay said alternatives like water lily, water spinach, and food waste (fish bone, rice water) became popular. Previously seen as inferior or inedible, these were now appreciated for their “untapped potential” — i.e., ground fish bones were added to dishes and rice water was substituted for mother’s milk.

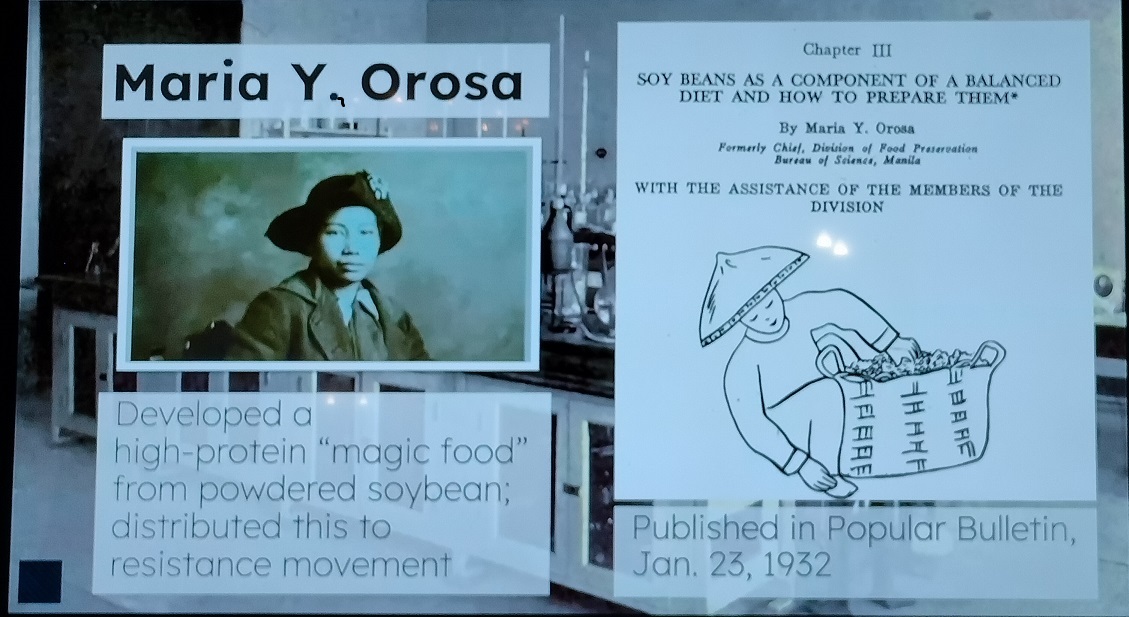

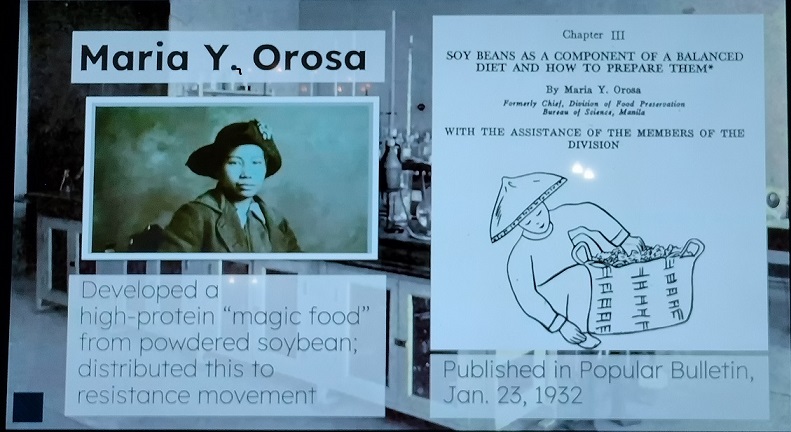

In “Extinguishing a Spark: The Impact of WW2 on Philippine Scientific Efforts,” co-authors Diana Marie Aguila and Lorenzo Thomas Lazaro said soybean became a food source. The high-protein powdered soybean — tagged “magic food” — was developed by food scientist Maria Orosa and “given to the resistance movement,” they said.

(Per writer RC Ladrido, Orosa was a member of Marking’s Guerrillas, a Filipino resistance group, and her “magic food” was distributed to POW camps in Los Baños in Laguna and at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila.)

Japanese atrocities

Besides the food crisis, Filipinos faced the Kempeitai, Japan’s military police force, whose officers were trained to suppress Filipino guerrilla forces through methods of interrogation like beating, burning, electrocution, and the “water cure.”

In the paper “Wartime Atrocities of the Oie Butai in Negros Oriental,” Dr. Justin Jose Bulado discussed the brutality of Class C war criminal Col. Satoshi Oie, the commanding officer of the 174th Infantry Battalion Oie Butai stationed in Dumaguete, Negros Oriental in June 1944. (Online research produced this definition: A Class C war criminal is one tried and found guilty of crimes against humanity by the International Military Tribunal for the Far East in Tokyo after WWII.)

Bulado said Oie was responsible for the grisly fate of district engineer EJ Blanco, whom resistance fighters had asked to draw a blueprint of the Dumaguete airport showing the exact location of the Japanese military planes. The map was sent to Gen. Douglas MacArthur in Australia, and Dumaguete airport was subsequently bombed and the Japanese planes destroyed. Blanco and his assistant Jovenal Somoza were arrested and tortured at Silliman University, and their bodies thrown into the sea.

Oie also massacred 23 civilians in Calindagan — per Bulado, a retaliatory move against the guerrillas who killed Mayor Tomas Merced, a Japanese lackey. Bulado added that the infantry’s violence escalated after retreating to Valencia (formerly Luzuriaga) in Bacolod with “the impending arrival of the Americans.”

POWs

Mark Anthony Cabigas in “Pasay POW Camp: A School Turned Hell” said the Pasay Elementary School (now Jose Rizal Elementary School) in Manila was an internment camp for American soldiers and medical personnel. The school had 500 prisoners, a number that burgeoned to 700 in 1942. Prisoners generally slept on bamboo pallets with a woven mat; ranking officers slept on mattresses. The camp was enclosed in barbed wire to prevent prisoners from escaping. Those caught were subjected to beating, water cure, and, at the extreme, beheading.

Cabigas said food was insufficient for the prisoners who worked as laborers in Nichols Field, but that the starving POWs were helped by Nancy Norton, who smuggled food into the camp, and Claire Philips, who bribed officers to bring food to the prisoners.

In Tarlac, the Horyo POW camp held American soldiers (15 generals and 106 colonels), their aides, and orderlies who contracted dysentery because of the camp’s poor sanitation, said Rhonie de la Cruz in “Horyo: The Account of WW2 American POWs in Tarlac.” However, Horyo was still judged as a better POW camp because the mayor provided food and soldiers were not tortured under the watch of Col. Shiro Ito who, according to De la Cruz, “was kind [and] humane to the soldiers.”

(Conversely, suspected Filipinos guerrillas and their families suffered under the Kalipunan ng Mga Pilipino, or Makapili, a paramilitary group of Filipino informers and spies, wrote Maria Syjuco-Tan in “The Makapili and Other Paramilitary Groups.” Formed by the Japanese in November 1944, the Makapili was said to be more cruel than the Japanese. Its members detained and subjected suspects to water cure, threatened their families, looted and burned houses, and massacred women and children.)

Losses

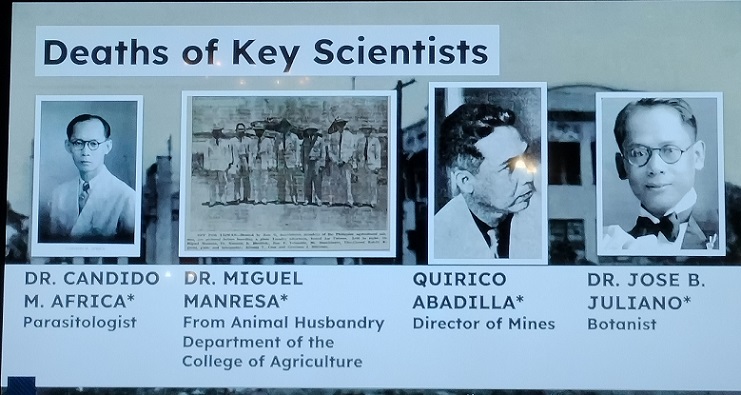

The loss of lives and resources was enormous. Aguila and Lazaro said the Japanese bayoneted key scientists, including Dr. Candido M. Africa (parasitologist), Dr. Miguel Manresa (former head of the Animal Husbandry Department), Quirino Abadilla (Director of Mines), and Dr. Jose B. Juliano (botanist). Former Bureau of Science chief Orosa died of shrapnel wounds at the Malate Remedios Hospital.

Aguila and Lazaro added that the destruction of the scientific library, School of Medicine and School of Hygiene and Public Health, and herbarium, amounted to a loss of $2 million, including 300,000 volumes of library materials and 305,367 herbarium specimens.

The Japanese also tried to appropriate Dr. Jose Rizal. Early Japanese propaganda alleged Rizal’s Japanese ancestry and admiration for Japan, said Dr. John Lee Candelaria in “‘If Rizal were Alive’: Rizal as Japanese Wartime Propaganda.”

Candelaria said Rizal’s “orientalizing” included journalist Ki Kumura claiming a 1,500-year Philippine-Japan connection; the 1942 Rizal Day becoming a demonstration of Filipino-Japanese unity; the essay contest “Rizal as an Orientalist” pushing for a scholarly validation of Japanese propaganda; and The Tribune, a prewar English-language newspaper seized by the Japanese, arguing that Rizal could have avoided martyrdom if he had stayed in Japan.

Freedom fighters

For an effective military campaign against the Japanese in the Philippines, the Americans had to stop the malaria outbreak with quinine made from cinchona bark (Jesuit’s Bark). Of the 75,000 American and Filipino soldiers, 24,000 came down with malaria, stated Rene Michael Baños in “Quinine from Bukidnon help Allies in WW2.”

Baños said Col. Arthur Fisher introduced cinchona bark in the Philippines. Fisher developed the plantation in Bukidnon, gathered the bark during the period 1942-1945, and tested the quinine tablets on 4,000 malaria patients. The tablets were also flown to the malaria-afflicted American and Filipino soldiers in Bataan by Bill Bradford in his “old Bellanca plane named Old Number 9.”

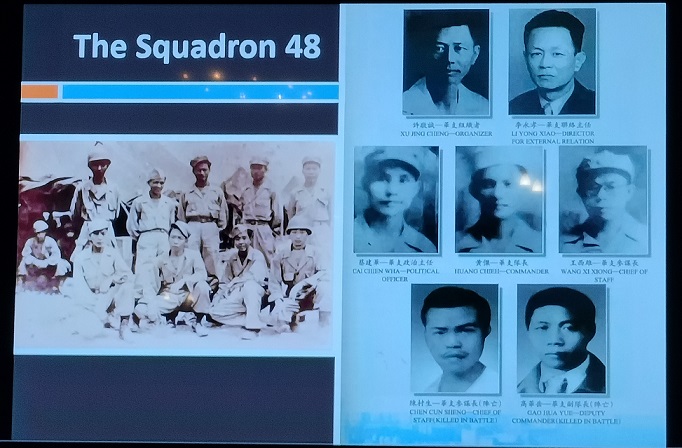

The Filipino Chinese also fought against the Japanese, according to Aquino Lee, former president of the Descendants of Wha Chi Guerrillas. In his paper “Wha Chi & The Filipino-Chinese Guerrillas,” Lee said Wha Chi (aka Squadron 48) was formed in Manila in May 1942 to combat Japanese aggression and protect the Chinese. It was decommissioned in September 1945.

Lee said squadron members were mostly from the Chinese working class, who only had seven rifles and two handguns collected from dead soldiers. In 1942, Wha Chi moved from Manila to Arayat, Pampanga, and fought alongside the guerrilla group Hukbalahap. In 1943, the two groups killed more than 30 Japanese soldiers in a single attack. In the same year, the squadron crossed the Sierra Madre from Mt. Arayat to get to Southern Luzon, and, by August 1944, the squadron’s activities had encompassed Northern and Southern Luzon.

History lessons

Conferences like “War & Memory” are few and far between, insufficient to cover gaps in Filipinos’ history education. It’s worrying that many Filipinos are oblivious to the Philippines’ colonial history, and to the struggles against Spanish, Japanese, and American colonizers. Philippine history is no longer taught as a standalone subject except in “grades 5 and 6 and in a college class called “Readings in Philippine history.”

It’s a quantum leap from learning basic history to participating in higher-level discussions. While engaging in retrospection is critical, it will not happen unless Philippine history is taught to young Filipinos, and taught without distortions in historical truth.

Educating Filipinos on their own history is a move critical to stopping the spread of the idea that fighting for freedom is a trivial pursuit.