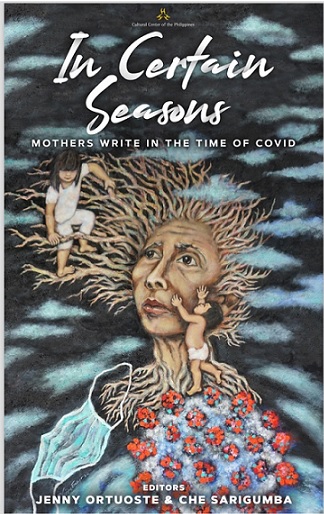

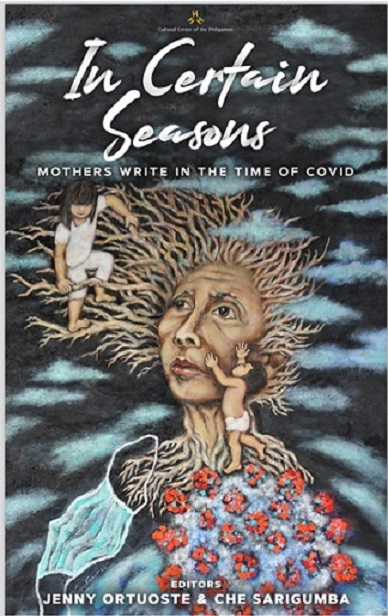

Filipino mothers bear the brunt of lives disrupted by the ongoing global pandemic, as detailed out in an e-book, In Certain Seasons: Mothers Write in the Time of Covid, 2020, published by the CCP Intertextual Division and its partner, the Philippine Center of PEN International.

Forty-one writers (who are also mothers and working women) document their own thoughts and experiences in a literary collage of stories and poems in English and Filipino.Imelda Cajipe-Endaya’s cover design is titled Salinlahi’y Iligtas (2020) in acrylic with sand on canvas.

The stories offer a shared experience of what women usually do or expected to do, even under Covid-19, e.g., the traditional roles of cooking, cleaning, house management, and taking care of kids and parents. The balancing act goes on and on. Amidst its banality, everyday life becomes a war against that invisible virus.

But beyond such conventional roles, the book is a journey into the mothers’ most honest selves in the time of the coronavirus, revealing a vortex of emotions in keeping home and family intact and whole.

A safe place

When our world shrank to four walls since the March 2019 lockdown, the family house becomes the 24-hour center of working, schooling, and learning as recounted by single parent Adelle Chua’s Nest Never Empty. It has become a sanctuary more than ever, as echoed in Eunice Barbara C. Novio’s Yet, We Had Each Other. Residing in Thailand, she describes its initial lockdown, and spending time with three grown-up children at home, caught in travel disruptions and cancelled flights.

The juggling of work and children goes on in Sabay: Buhay-Guro, Buhay-Nanay by Maricel Padua Lopez who narrates the challenges of working from home as a teacher and at the same time, guiding her kids in their online schooling.

Lalaine F. Yanilla-Aquino shares her happiness inhaving a complete family with husband and four sons during the early lockdown months in Rollercoaster of Emotions, Blessings in Disguise at Reversal of Roles. With her major surgery, sons and father took care of her and everything else. And learned to cook they did, with gusto.

In Cocooning With No Complaints, Neni Sta. Romana-Cruz sees the lockdown as a blessing, in slowing down at home to deal hopefully with years of accumulated files and to clear “one’s life mementos and sentimental junk.”

Rising up to the occasion, Alma Anonas-Carpio carries on a family tradition of entrepreneurial guts after retrenchment, just like what her mother did. She uses her tiny kitchen and cooking chops to sell meatloaves with Gouda cheese and more with her twin daughters in Pandemic Kitchen.

In Dreaming of When It’s Over, Babeth Lolarga reminds us to count our blessings and stay grateful. Recuperating after a knee surgery, she muses over past delights of food and concerts, and pines for faraway Baguio where husband awaits.

Pain is always around

Directing Grace by Mia Tijam is an emotive paean to grief and difficult decisions with grace. Drawing you into her turmoil, it is an understatement to say that a daughter taking care of a father for 51 days in a hospital and running a household requires a lot of love and courage.

Winnie Velasquez in Takipsilim ni Granny Google shares her 88-year old mother’s drastic change from someone full of life to becoming so quiet and listless, suffering from social isolation.

A short prayer oozing with contempt and sarcasm, Heidi Emily Eusebio-Abad’s Isang Panalangin pleads for some mañanitas for entertainment in order to forget hunger pains, and to add more dolomite to that fake white sand along the bay. She notes that the act of praying is her only strength left in this long lockdown.

The outliers

Two stories about edgy lives remind us that we are all in this together. How do street people manage under lockdown? It is mostly the same as usual, surviving on the kindness of neighbors and strangers, in Mae Ann Reginaldo’s Mga Lalaki sa Cubao sa Panahon ng Lockdown. In Ponx Not Dead, Heidi Bailon Sarno pays tribute to street artist Gutson Alvarado Heyres of Cavite. He may be unknown to the literati crowd but his persona and works live on in the minds of friends, even in death.

In Certain Seasons is personal, and it is also intentional. After taking care of the family and everything else, how do Filipino mothers look after themselves and address their own needs? Hope Sabanpan-Yu points a way in recharging herself in The Garden Is Always There. More answers are needed for this question.