By NORMAN SISON

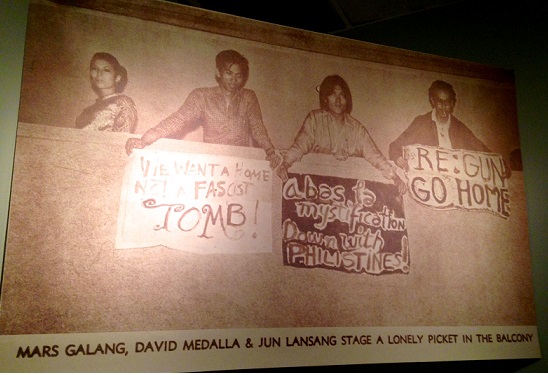

A blown-up photo of a mini rally at the balcony of the Cultural Center of the Philippines 45 years ago at the exhibit “Articles of Disagreements” at the Lopez Museum adds to reminders to the current generation of Philippine democracy’s darkest hours.

The event in the picture was the gala of the Cultural Center of the Philippines on Sept. 8, 1969. It First Lady Imelda Marcos’s evening. After all, the CCP was her first pet project.

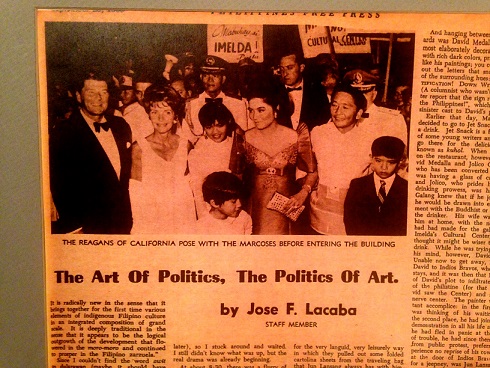

Leading the list of who’s who as guests of the Marcoses were then California governor Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy, who were representing US president Richard Nixon. Philippine society’s creme de la creme were there.

At around 8:30, there was a buzz of activity outside. Thinking that the Marcoses and the Reagans had arrived, three artists went up to the balcony overlooking the lobby. They unveiled their placards made of cartolina and staged an instant rally.

“We want a home not a fascist tomb,” declared a protest placard held by Mars Galang, referring to the CCP. “Re: Gun — Go home,” blared another, held by Jun Lansang, the pun aimed at Reagan. Sixteen years later, the Marcos-Reagan connection would figure prominently in 1986 when Reagan, by then the US president, backed Marcos until the dictator was chased away by the People Power Revolution.

A police officer was quick to grab by the arm one of the three artistic protesters, David Medalla, to lead them away. They protested, saying they had invitations to the gala. They were eventually allowed to stay to the chagrin of the CCP management.

It was still a good three years before Marcos imposed martial law, but that evening in 1969 was a glimpse of things to come and last to this day.

The night was hounded by two rallies actually. On one side were students, writers and artists protesting the construction of the CCP. On the other were supporters of Imelda Marcos.

Opposition leader and then senator Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., President Benigno Aquino III’s father, had attacked the CCP in a privilege speech because of the cost — in today’s Philippine political parlance, overpriced— an expense that an impoverished nation could have had better use for.

The construction bill had ballooned to P50 million, overrunning the budget by P35 million. Imelda Marcos and the CCP board had borrowed US$7 million to finance the remaining cost.

However, there were protesters who saw something else behind the CCP. Was it built for the sake of art? Or was it built for something sinister?

“For politics so pervades our life that even art cannot escape its taint, even culture becomes a political issue, and dissent in whatever form, nonconformity however innocuous, is immediately interpreted as obscene, or subversive, or partisan,” wrote then 24-year-old journalist Jose Lacaba in the September 20, 1969, edition of Philippines Free Press.

Lacaba would later attest to that. He was jailed during martial law for opposing the Marcos dictatorship. Years later he achieved critical acclaim for his 1984 film “Sister Stella L.” and other works that depicted the conditions under martial rule.

“Articles of Disagreements,” which runs up to Dec. 20, provokes the question of what is art and what is not. Is a folder full of bond paper used as placemats “art”? How about a tabletop decorated with magazine illustrations?

Then, there is also the debate over the purpose of art.

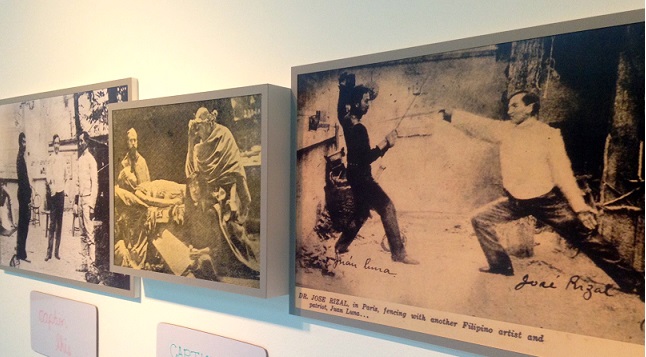

For Philippine national hero Jose Rizal, it served as proof that Filipinos of his day were not innately inferior because of their race, but that they could be the match of Spaniards, the colonial masters of the time.

“The patriarchal era of Filipinas is passing. The illustrious achievements of her children are no longer consummated within the home. The Oriental chrysalis is leaving the cocoon,” he declared in a florid toast on June 25, 1884, honoring painters Juan Luna and Felix Hidalgo for bagging the gold and silver medals at a major art contest in Madrid.

For the Marcos dictatorship, art was for the upliftment of the nation.

“In our nation’s Constitution, it is stated that the promotion and enhancement of art and culture must be the prime concern of the state. However, if in the implementation of this constitutional provision, it is done to suit the vested interests of a few, then the state might as well disregard this provision,” wrote sculptor Napoleon Abueva, one of the nation’s foremost artists, in a 1975 art magazine critique.

Today, Marcos loyalists list the CCP among the stellar achievements of one they claim to be the “best president the Philippines ever had.” On the other hand, Filipinos who were traumatized by the Marcos dictatorship see it as the foremost example of Imelda Marcos’s so-called “edifice complex.”

It only underscores the inseparability of arts and politics.