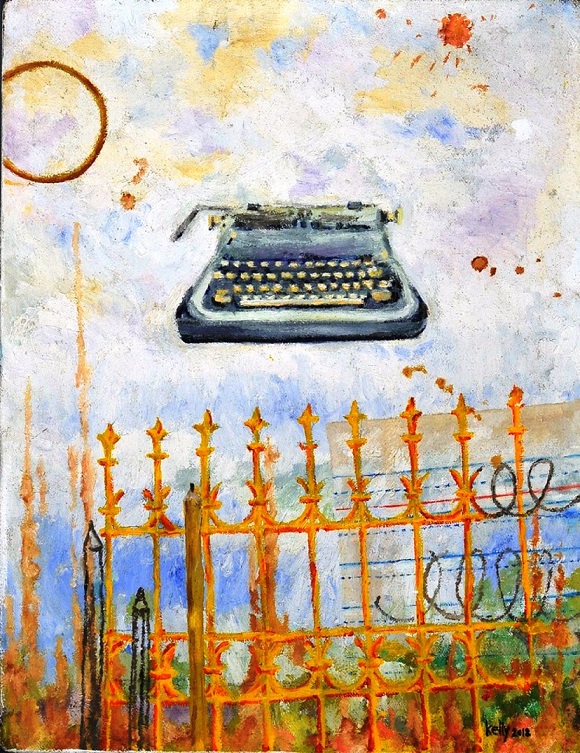

Every Grain of Sand, oil on canvas

Painter Kelly Ramos’ desire for herself is simple—to keep on exhibiting at galleries and museums and express all the ideas she has for shows inside her head. In her latest solo, “Love Letters from Tawang,” at the Indigo Gallery of Bencab Museum, the paintings look like love notes sent from the mountain to the world.

She has reason to frame the show of 28 paintings like love letters, confessing that she is “a shy person” visited by “periodic bouts of mild social anxiety where I feel like hiding from the world for a while and it becomes super hard for me to speak in public.”

Despite the anxiety, what interests her are people. She said, “I want to know who they are, what shapes them, the psychology of each individual. I thrive on good conversation. So creating visual love letters, these personal notes of joy from where I stand in the world to each of you lovely people is easier to handle than making a grand statement to a big impersonal crowd.”

The word “tawang” is the name of that barangay where Ramos and her sons were living and the basis of images in the paintings. Norwin Gonzales of Northern Dispatch told her that tawang may mean “high mountain” because there is a Tawang in Northern India, historically part of Tibet. She said, “It’s a happy discovery that fits in beautifully with the show.”

A Hard Rain’s A-gonna Fall, oil on canvas

Although she doesn’t live in Tawang anymore, she said, “The distance of time and place is necessary when trying to do a reflective project like this. It’s hard to see what’s in your face, when you’re living something day-by-day. I’m able to make these paintings and choose what images to paint because I’ve already stepped back, I am not living there anymore, because it has been a while since I moved out and elsewhere.”

Her family spent two to three years up in that mountain, but are back in Baguio in a regular house closer to town. Of that time in the mountain, she recalled that there were “more chores to do—buying supplies took a lot of preps, energy, and time. The distance to the center was also its appeal. ”

Although little money came in, the mountain provided. She said, “Water was free from the sky, with the rain-catcher set up on the roof of the main house. There were bamboo shoots, passion fruit, sayote, guavas and mushroom, depending on the season. Sometimes the farmer from the nearby lot would let us pick the remnants of their harvest: spinach or brocolli tips.”

When she woke up, she would pick coffee for drying and clear the area of weeds, pick firewood for the night’s bonfire. In the evening, she’d make a fire and cook food for the dogs and cats over the fire I made. There was an owl that screeched every night. This grass owl found its way in one of the small paintings in the show.

Blowin in the Wind, oil on canvas

It is this experience of mountain life that Ramos wanted to share with viewers. She repeated, “I was not in that mountain anymore when I painted all these, although I am still in Baguio and Baguio IS a mountain, too, and yes, it is restorative and inspirational.”

For the show, Ramos asked young artists Gaea Claver, Erica Gonzalez and Kabu Palaganas to serve as her assistants so she could finish on time and fill up the space. She recalled

running out of paint towards the end of the process, but fellow artist Kora Dandan Albano gave her some tubes.

Ramos was so grateful considering “it’s hard to find oil paints up here. These oils were bought in Manila, but she offered them to me. You may probably notice some flecks of Prussian blue in the panoramic night-time landscape painting, ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue.’ That’s Kora’s color. Usually I get only cobalt and ultramarine blues. What I am trying to say is that it was crazy difficult to do this big solo, but I had a lot of help. Like raising a child, it took a village!”

Asked who of the landscape artists whose landscapes she admires, she replied, “I like Amorsolo, but I don’t know if I am influenced by him. I like Van Gogh definitely, Winston Homer’s seascapes and the stark lighting of Wyeth’s landscapes. I like Roland Bay-an when he’s not doing the Bencab style.”

Maggie’s Farm #3, oil on wood

She continued, “More than being influenced by the style of these other artists, what I like about them is how they tell personal stories of their lives within their paintings; how Amorsolo romanticized the Philippine landscape and it’s maybe because he was painting for an American audience in the 1920s, and how Van Gogh produced expressive paintings of commonplace scenes from his everyday life, and how Wyeth’s ‘I paint my life’ realism actually holds a secret symbolism.”

A single mother, she agreed that as artist mothers, “we have years to figure out the work-life balance. I don’t know if I did succesfully balance my children’s demands while working for this show. I guess we should ask them? They aren’t demanding. I paint, I cook. I occasionally do laundry, paint again, occasionally clean house. I spend time with them, paint again. Take them out, come home and paint again.”

She has strong convictions about education and its worth because by choice she decided to home-school her children. She said, “We are so caught up in the idea of education equals worth and that schools are the only legitimate avenue for it. Raising my children, when they were in school and now while they are learning without schooling, has always been a joy. The difference is that we did away with what seems like unnecessary imposed stresses so we focus on the essentials of learning, of parenting, of family life, connecting with each other on a daily basis, being present, spending time on what truly interests us.”

She added, “It was by choice. For years I have been chafing and grumbling at the inadequacies of the school system; the bad-quality textbooks, curricula that don’t make sense anymore, authoritarian rules, slow pacing, ridiculous expense, etc. Then there was the bullying in schools.”

Kelly Ramos with cat.Portrait by Studio 37

A migrant to Baguio, she said when she moved up, she heard “the pronounced glottal stop of my maternal grandmother’s voice everywhere. She was an Ilocana from Ilocos Norte who married a Mindanaoan and settled there long ago. Living here now, I feel like I am tapping into some hidden secondary root in my Lola’s family tree that is still anchored around these here parts.”

She continued, “When I was new here, I reveled in the anonymity, in the arm’s-length closeness of new acquaintances. I love being the invisible observer. But I am moving past that role now, having been here for about five years already. Maybe we will not here for good, but who knows? I haven’t made plans for a permanent stay. I am not looking for a house and lot to buy, for instance. All I can say for sure is that I am here for now. Wherever I will find myself in the future, I will take this Baguio experience with me.”

Bencab Museum is at Km. 6 Asin Road, Tadiangan, Tuba, Baguio. Gallery hours are 9 a.m.- 6 p.m., Tuesdays to Sundays. “Love Letters from Tawang” runs until April 1.