By NORMAN SISON

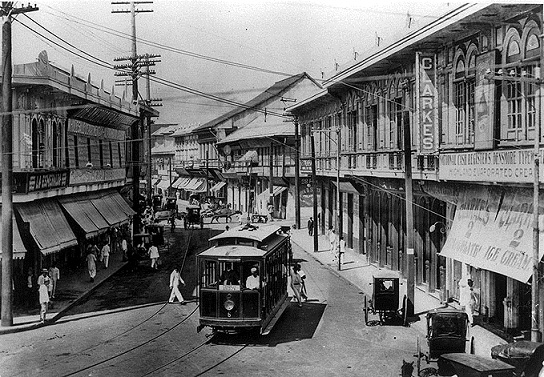

To remember the glory days of Manila would be to remember the electric trams that once plied its streets and contributed to the city’s reputation as the “Pearl of the Orient.”

At Museo Pambata, children frolic on a replica horse-drawn tranvia (“tram” in Spanish) in a room dedicated to the city’s history under Spanish colonial rule. In nearby Intramuros, the walled Spanish enclave that formed the core of the capital, tourists are taken around on a replica tram.

“To me, seeing photos and videos of tranvias plying Manila’s less crowded roads looks like an idyllic, slower-paced lifestyle that was peacetime Manila,” says Ricardo Jose, a professor at the University of the Philippines and an eminent World War II historian.

For today’s generation of Filipinos whose patience and sanity are tested daily by chaotic and snail-paced traffic, it is difficult to imagine that Manila actually once had a public transportation system — like it was a fable.

The ancestor of Manila’s light rail transit (LRT) system debuted in 1888. Operated by Compañia de los Tranvias de Filipinas (Tramway Company of the Philippines), the trams were powered, literally, by horses. Each coach carried 14 passengers only.

Tranvias de Filipinas’s central station was in Plaza San Gabriel (present-day Plaza Cervantes) in Manila’s Binondo district. It ran four lines: Intramuros, Tondo, Sampaloc and Malate. A grainy film taken in 1903 showed that Calle Escolta, then Manila’s shopping district, once had tranvia tracks passing through it.

By the eve of the Philippine Revolution in 1896, the tranvias had ferried 9.7 million people. To put that in perspective, today’s MRT Line 3, which spans the length of Epifanio de los Santos Avenue, carries over 600,000 passengers — per day.

Compared to electric tramways in Berlin, New York, Prague and other major world cities, however, the tranvias were, as one visitor to Manila put it, “very casual in operation”. The service depended on the professionalism of the driver and the health of the horse. Passengers even had to get off and help push the vehicle over inclines.

“But for Manila of the 1890s, the tranvias were still a cut above the chaotic jumble that had preceded them on the city’s unpaved streets,” according to writer Raul Rodrigo in his book Meralco: A Century of Service 1903-2003, referring to calesas or horse-drawn buggies — which still ply Manila’s streets mostly for tourists.

If the trams were to be modernized, they needed to be electric.

In 1903, shortly after the United States took over from Spain as the Philippines’ colonial ruler following the Spanish-American War, the government began taking bids to build Manila’s first electric tramway. The franchise went to the lone bidder, Manila Electric Railroad and Light Company, better known by its acronym Meralco, which then bought Tranvias de Filipinas.

The first Meralco trams rolled out in 1905. They were about the size of today’s buses, with room for 50 passengers per car. Tickets were at 12 centavos for first-class, in the front of the cars, and 10 centavos for second-class at the rear.

The 1920s was Meralco’s golden age after the company modernized the system. “The upgrade was so extensive that several foreign observers judged that Meralco had the best streetcar system in Asia, besting even Japan, a country which has a long-running affair with trains,” according to Rodrigo. By 1925, Meralco carried 35 million passengers or 95 times the population of Manila.

The greater mobility brought in a fact of everyday life that Metro Manilans today know all too well: commuting. So was overcrowding — even for a city of 600,000 — as people from the provinces flocked to the city to find work.

The trams were destroyed during the 1945 Battle of Manila, when American forces rooted out Japanese troops occupying the city. Meralco didn’t restore the trams because it was too costly, deciding instead to shift its core business to providing power.

The transportation shortage prompted Filipinos to solve the problem by modifying surplus US Army jeeps to carry passengers — and the jeepneys (coined from the words “jeep” and “jitney”) were born.

“With the death of the tranvia, the buses and jeepneys took over. I guess these were temporary solutions, but the government never did seem to consider more permanent solutions,” says Jose, who recently gave an Ayala Museum lecture about life after the Battle of Manila.

The Philippines had to wait until 1984 for a dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, to erect the country’s first LRT system — Line 1, which runs north to south, from Pasay City to Caloocan City. However, jeepneys still form the backbone of Manila’s public transportation system.

The government has embarked on a building program to expand Manila’s LRT system by extending existing lines and building new ones linking the capital to the suburbs. It also, along with the University of the Philippines, is developing an automated monorail system.

“I do wish that the tranvia would be revived to finally replace the jeepneys,” says James Aaron Mangun, a founder of Philippine Railways, a Facebook-based train enthusiast group. “However, given the population density and the reduced amount of available space, we would have to be realistic about building them the same way as they were built before.”

There is also the realities of modern commuter life to consider. “They would probably not have survived the increasing demands for speed,” says Jose. “So, we look back wistfully at those less stressful days.”