Text and photos by ELIZABETH LOLARGA

IN the 19th century, Juan Luna, Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, Jose Rizal and other expatriates in Europe were already doing their versions of the “selfie” and “wacky shot.” They were unaware of the greatness that was their destiny.

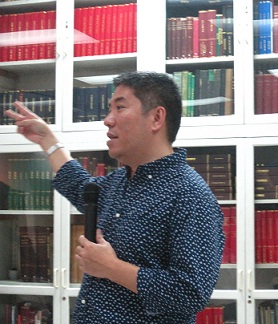

Historian Ambeth Ocampo, who specializes in 19th-century Philippines, including the arts from that period, lectured on the lives of the two painters, how they intersected with Rizal’s and how their art would be part in shaping an emerging nation.

Historian Ambeth Ocampo, who specializes in 19th-century Philippines, including the arts from that period, lectured on the lives of the two painters, how they intersected with Rizal’s and how their art would be part in shaping an emerging nation.

He supplemented his talk, part of the “Understanding Philippine Visual Art” series of Lopez Museum and Library and Ateneo Art Gallery, with rare slides of the youthful patriots in makeshift costumes, staging funny tableaux in the artists’ studios, apartments or Parisian cafes when the photography was a novelty. There is one of a drunken Rizal about to throw an apple on a fellow sprawled on the floor, apparently passed out from too much drinking.

Ocampo said, “Although they don’t look heroic enough, they showed what life was like then.”

He said Luna was the more colorful of the two painters. The third of seven children born in Badoc, Ilocos Norte, his mother was a a strong woman ike Rizal’s. He added. “Early Filipino history books describe her as the greatest Filipino mother because she raised her five sons well and all became famous–Juan the painter; Manuel Andres, violinist although there is no recording of this ‘greatest violinist of his time’; Jose, a toxicologist; Joaquin Damaso became a governor and congressman, and Antonio, a pharmacist, was a general of the Revolution.”

Luna, a licensed seaman, saw people sketching and painting in his travels. He studied painting under Lorenzo Guerrero until the teacher advised him, “I have nothing more to teach you. Go abroad.” In Spain he studied romantic and historical painting under Alejo Vera and painted “El Ultimo Dia de Numancia” in 1881, echoing his later “Spolarium” that would win a gold medal (one of three, the other two won by others) at the Exposición Nacional de Bellas Artes in 1884 in Madrid.

Ocampo traced the whereabouts of the earlier painting to the Prado Museum’s collection, also in Madrid. The work was sent to a smaller museum in a Spanish province. He explained, “You don’t hang a Luna beside the works of Velasquez at the Prado.”

Hidalgo won one of 45 silver medals at the same exposition for “The Christian Virgins Exposed to the Public.” Ocampo compared these victories to “Manny Pacquiao and Lea Salonga doing well abroad, a feel-good moment for Filipinos.”

He said how people look at Luna and Hidalgo today “is framed by what Rizal wrote about them.” The quote ran: “(The painting) is all light, color, harmony…like the Philippines in her moonlit night or her tranquil days.”

Ocampo pointed out the contradiction in Rizal’s description beside what Luna painted: the blood and gore after a gladiator’s battle. Luna and Hidalgo painted in the academic manner with ancient Egypt or ancient Rome as their subjects and for which their prizes were given.

After the victory, Rizal gave a famous speech at the Hotel Ingles where he extolled the painters as glories of the Philippines, saying “Genius knows no country.”

Rizal’s brother Paciano undertook the first translation of Noli into Tagalog, with Rizal making the corrections in his own penmanship. Luna offered to illustrate famous scenes and characters like Sisa, Maria Clara, Padre Damaso, Doña Victorina, the chase on the lake, Basilio and Ibarra ringing the bells, among many. The original manuscript has since been lost while the priceless illustrations were destroyed in the last war. What extant images are only photographs of those black and white watercolors.

When Rizal returned to the Philippines, Luna asked him to bring some paintings to sell. Thus Rizal became his art dealer, receiving a 10 per cent commission from every sale with instructions to remit the money quickly to Luna who had a family to support in Paris. That list of paintings entrusted to Rizal is nowhere to be found.

Luna didn’t always affix his signature in studies or lesser works. The painter’s family authorized collector-dealer Alfonso Ongpin to sign these works “LVNA.” Many paintings went to Grace Luna de San Pedro, American partner of Luna’s son Andres. Andres had no heir. She bequeathed them to her nurse in the US until the Philippine ambassador recognized their value. The Far East Bank of the Philippines bought them, then donated them to the National Museum for a big tax deduction.