By DANIEL ABUNALES

Slides courtesy of Jarrett Davis

“They molested me while I was sleeping on the streets.”

“While I was sleeping, there was a person who put his hand down my shorts and videoed it.”

“(He gave me) a big Toblerone. I went to the…hotel with him. He had me take off all my clothes, and he took off his as well. We showered together. He put my penis into his mouth.”

These and other equally disturbing accounts come from boys aged 9 to 19 who work or live on the streets of Manila, particularly in the Tondo and Ermita-Malate districts.

They’re contained in a recent study, titled “They didn’t help me; they shamed me,” that looked in the plight of street-involved children and found that boys, like girls, are vulnerable to sexual abuse and physical violence.

The results of the study were presented Monday at the opening of the 20th year of National Awareness Week for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation at the Quezon Memorial Circle.

The research defined street-involved children as children sleeping in public places without their families, children who work on the streets during the day but return to their families at night, and children living with their families on the street.

The study, authored by Jarrett Davis for the international human rights group Love 146, interviewed in 2014 a total of 51 street-involved boys in Manila.

Thirty-three of the 51 boys had experienced “at least some form of sexual violence on the streets or within their communities,” according to the study.

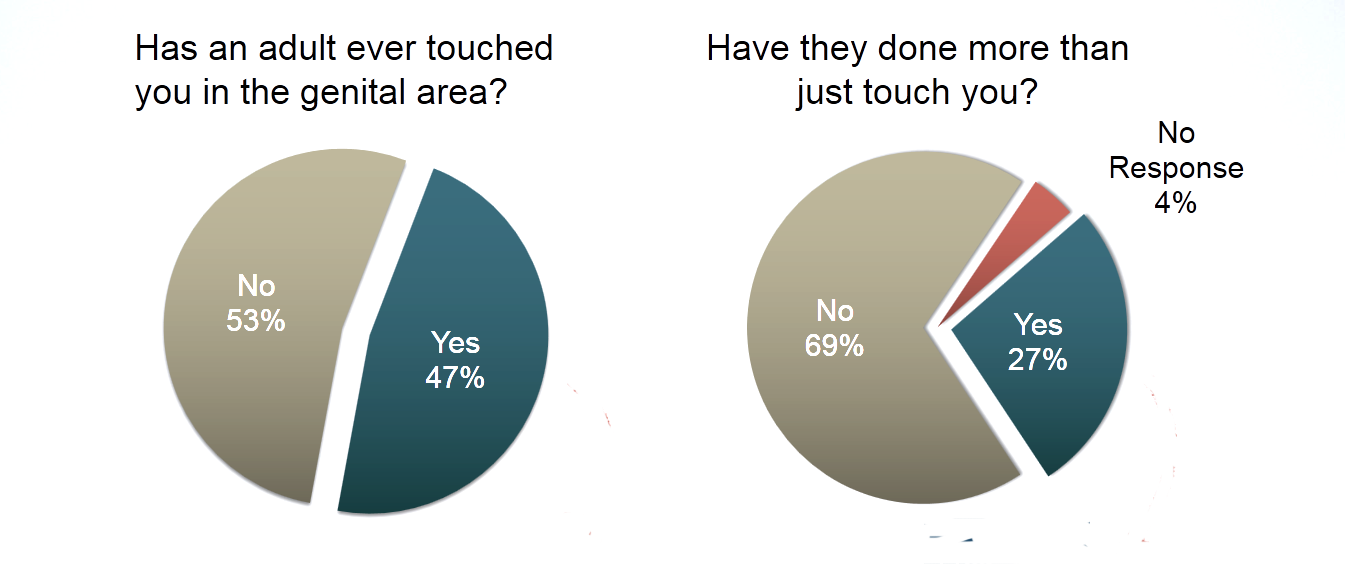

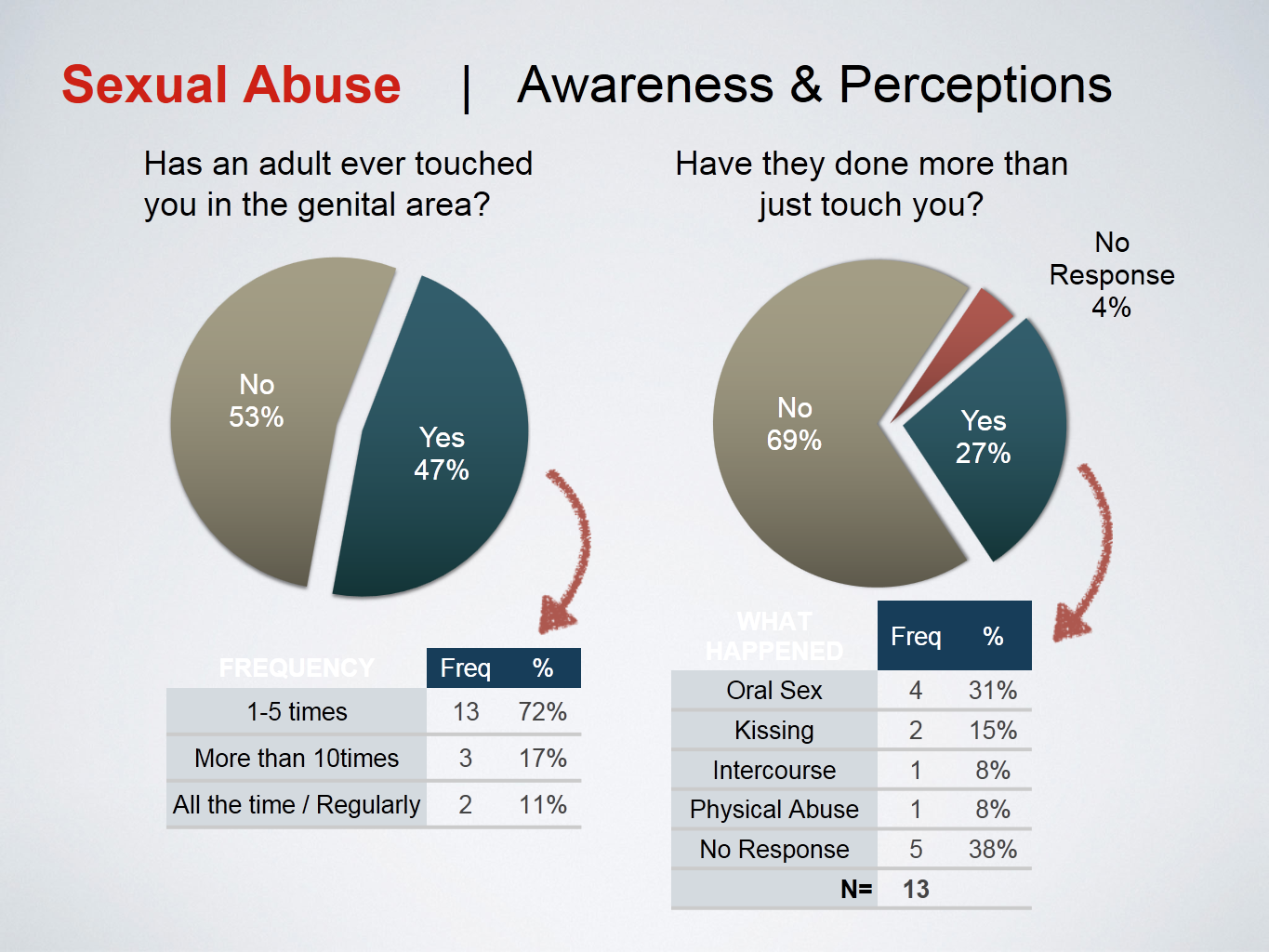

Twenty-four of them said an adult has touched them in their genital area. Thirteen of them said it happened between one and five times, three said it happened to them more than 10 times, and two said an adult did it regularly.

Thirteen confirmed that the sexual abuse went beyond touching, ranging from oral sex and kissing to intercourse and physical abuse.

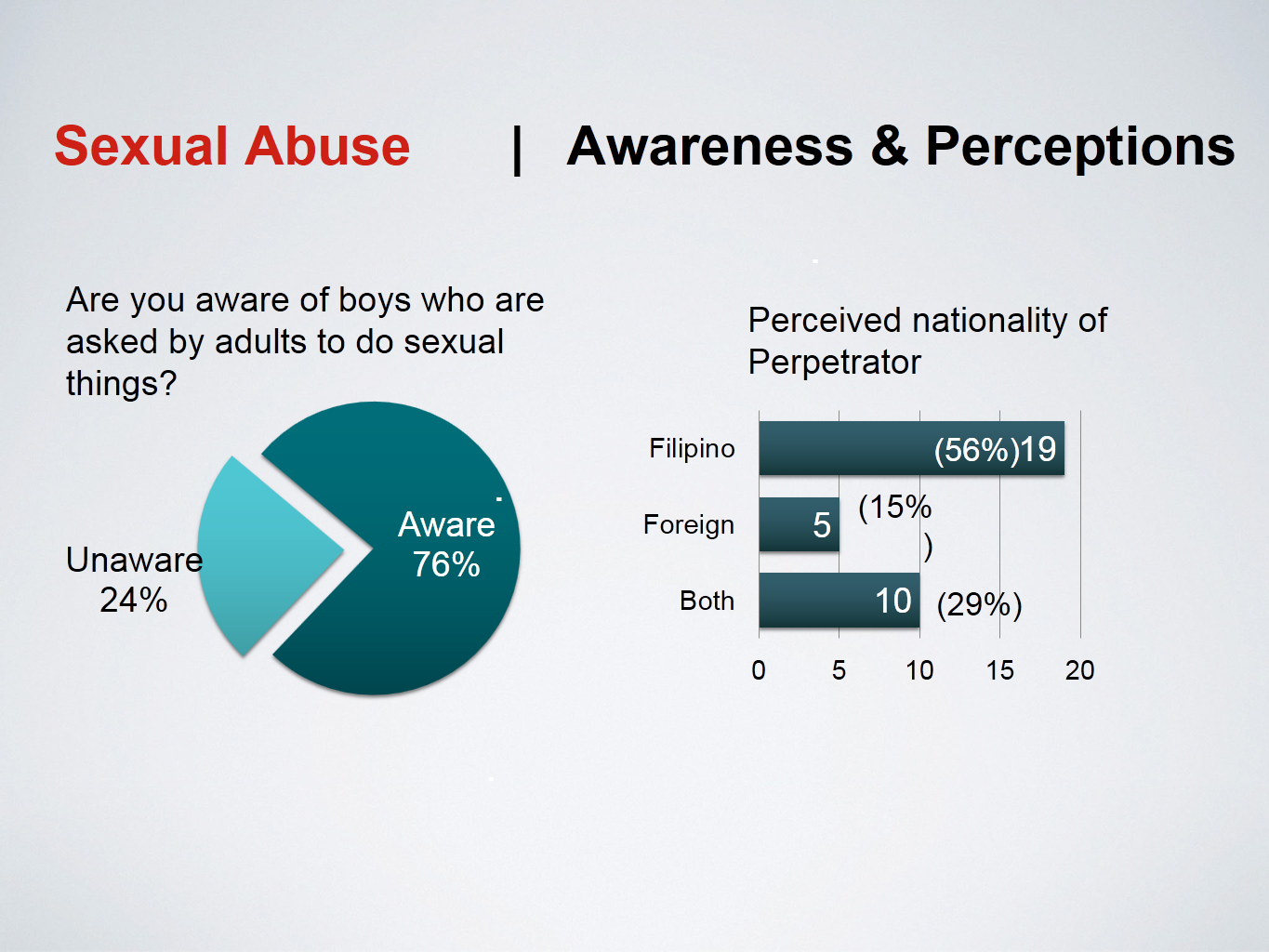

Thirty-eight boys also said they were aware of other boys who had been asked by adults, a mixture of Filipino and foreign nationals, to do sexual things in places such as along Manila Bay, a plaza in Tondo and on one of the major roads in Malate.

Another form of sexual abuse involved boys being filmed for pornography, the study revealed.

Three boys said they were filmed or photograph for pornographic materials. Twenty of them, on the other hand, said an adult friend or a complete stranger had shown them pornographic materials.

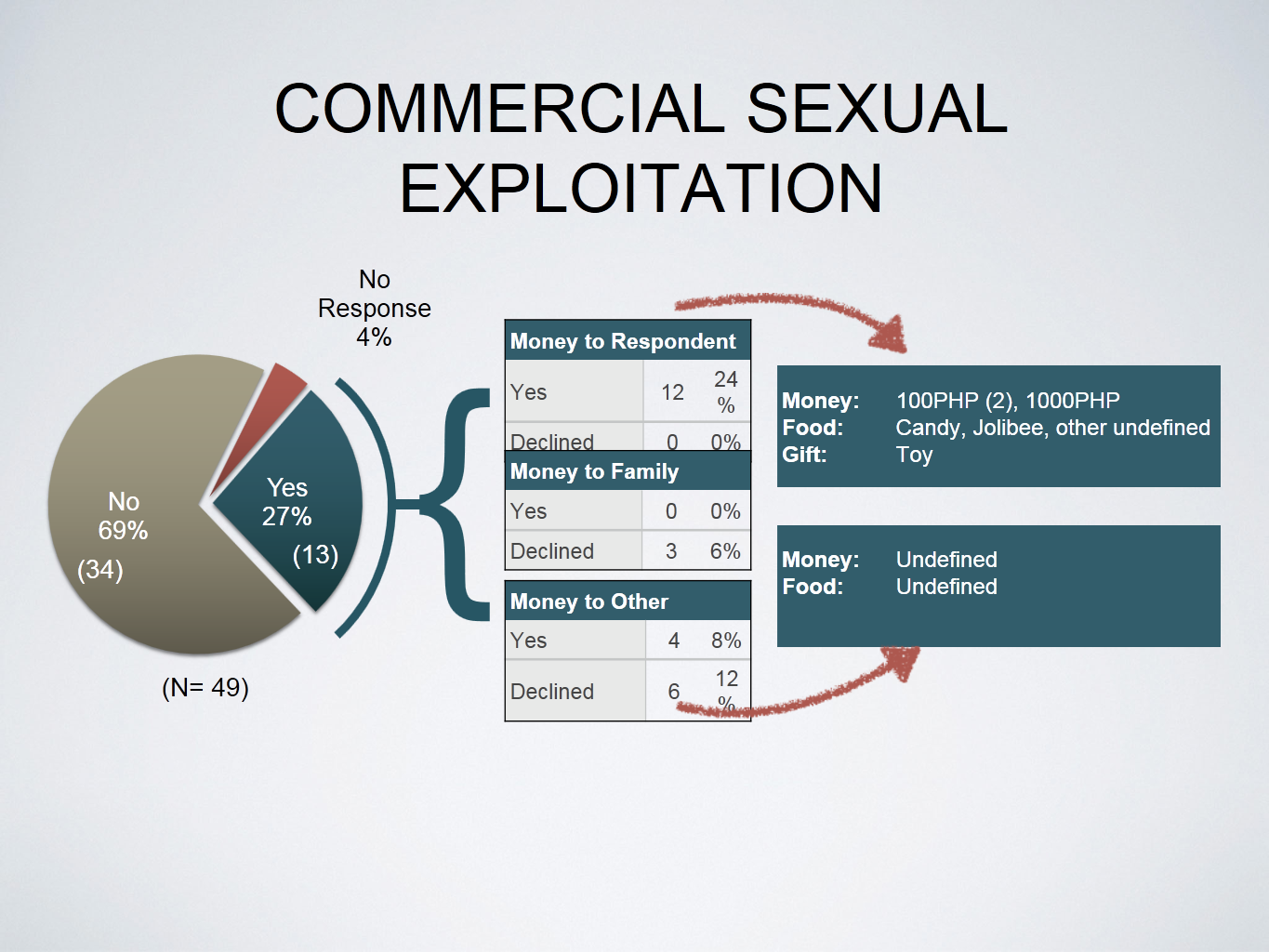

“They didn’t help me; they shamed me” also explored instances where the boys became victims of commercial sexual exploitation, or the offer of money, food or a gift to the boy, his family or anyone else in exchange for the child providing sex or sexual services to an adult. Thirteen of the 51 respondents described instances where they were sexually abused in exchange for money, food or a gift.

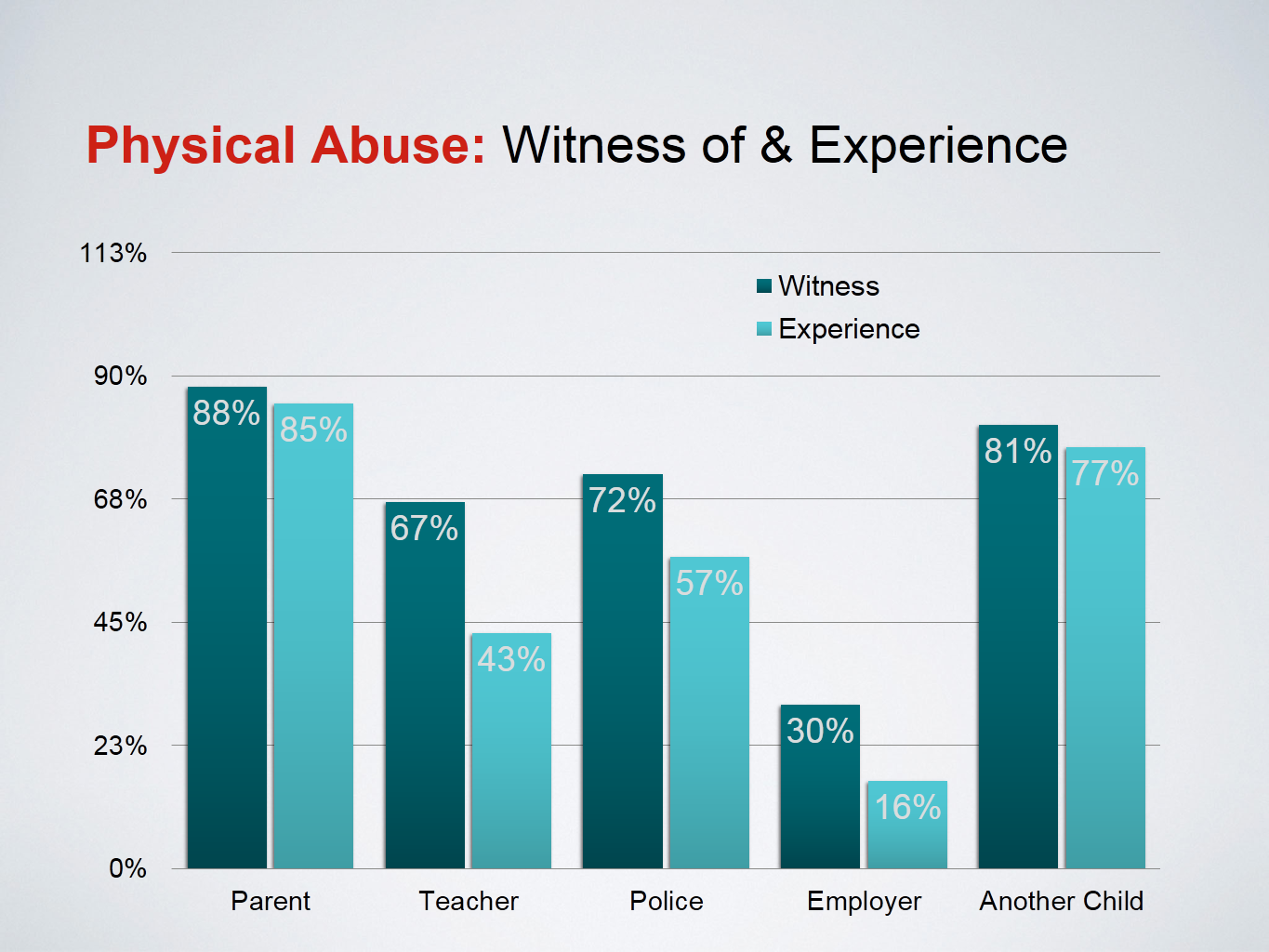

Aside from sexual abuse, 43 of the respondents reported having experienced physical violence from a parent, teacher, police, employer or another child.

A 13-year-old parking attendant said the police accused him of stealing and hit him with a baseball bat. A beggar, also 13, said a female cop “kicked me, slapped me in the face, stepped on my foot really hard and put me in handcuffs.” Two boys reported being “electrocuted” by the police.

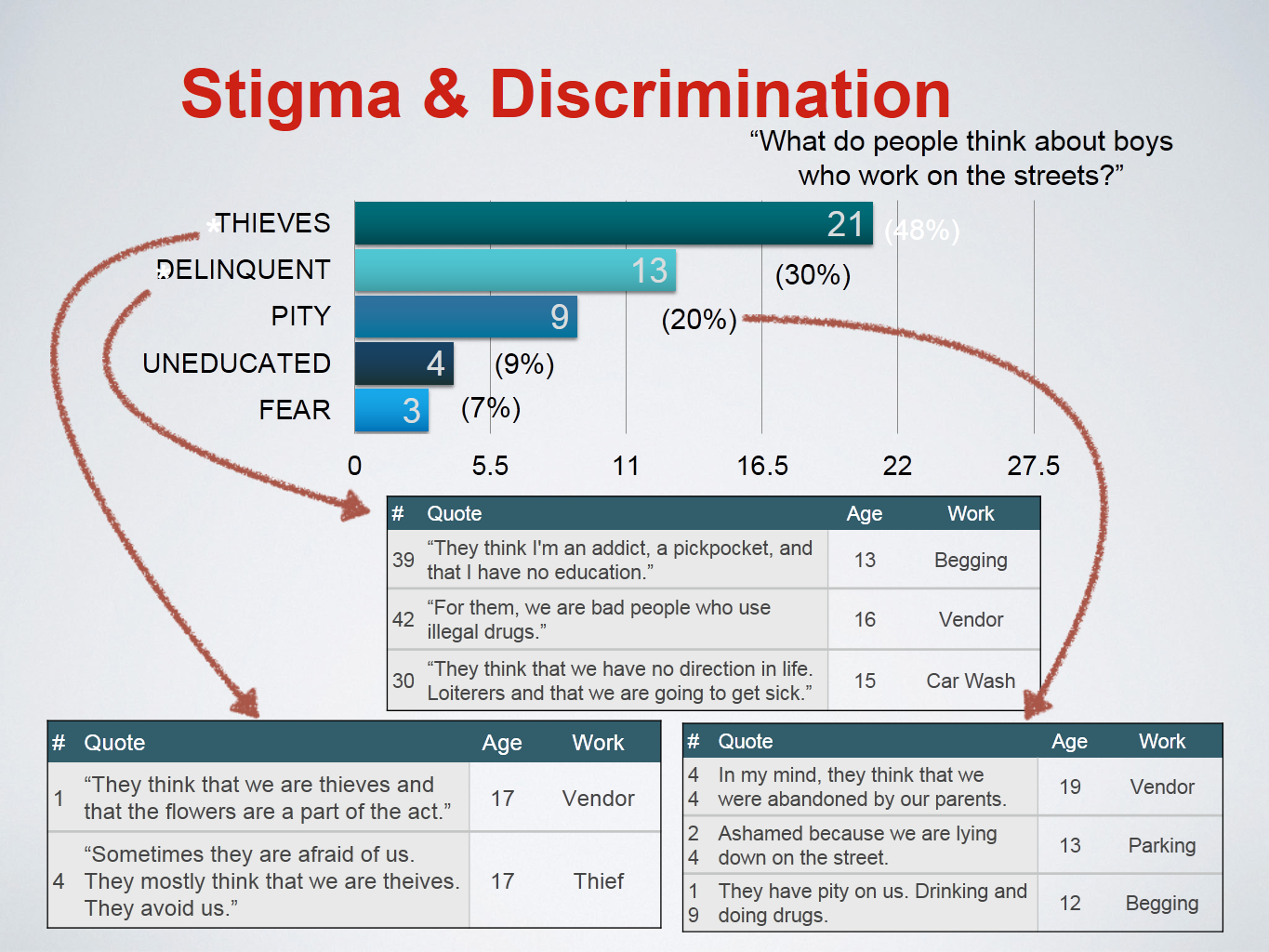

Thirty-two of them described a variety of antagonistic feelings they perceive people to have toward them; they said people consider them as delinquent, thieves and uneducated.

The study lamented that the vulnerability of boys to sexual abuse has been ignored because of the common belief that girls are more disposed to sexual abuse and violence due to their “gender and situation.” Boys are assumed as “better able to protect themselves,” it said.

As a result, government’s approach in addressing the problem of sexual abuse has left out the boys, the study said.

Data from the Department of Social Welfare and Development show 29 of the 1,401 cases of sexual abuse in 2011 involved males.

Quezon City Mayor Herbert Baustista said in a speech at the opening of the National Awareness Week for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse and Exploitation that the city’s social welfare office recorded 144 cases of child sexual abuse, 32 of which involved boys.

Crucial to addressing sexual abuse of boys is “understanding exploitation as exploitation” and not getting stuck on the gender framework, Davis said.

“When we say children, let’s actually in practice study children,” he said.

Council for the Welfare of Children chief Patricia Luna said in an interview that government assists children who are victims of sexual abuse and exploitation regardless of their gender.

She said programs are in place for both boys and girls but also acknowledged the need to reassess them.

“Siguro kailangan lang tignan natin anong klaseng approach, methodology or model ang pwedeng gamitin para sa mga lalake kasi syempre iba yung pang-aabuso sa babae iba yung pang-aabuso sa lalake (We probably need to examine what approach, methodology or model can be applied to boys because the abuse of girls is different from that of boys),” Luna said.

The U.S. Department of State’s 2015 Trafficking in Persons Report noted that the country’s protective services for male trafficking survivors remained scarce.

It noted that boys who were trafficking victims were placed in shelters for children in conflict with the law.

The report added, “(The) DSWD prematurely discharged them without investigating for trafficking indicators, which negatively affected their rehabilitation.”

Davis’ study showed that the help the street boys got when they confided the abuse to people close to them varied.

The brother of a 14-year-old victim stabbed the perpetrator. The mother of an 11-year-old launched a hunt for the gay person who molested her child so she could file a case. The parents of another 11-year-old talked to the child that abused their son.

A 13-year-old, however, said help never came. That also happened to a 14-year-old when he turned to his friends for comfort. “They didn’t help me, instead they shamed me,” he said.