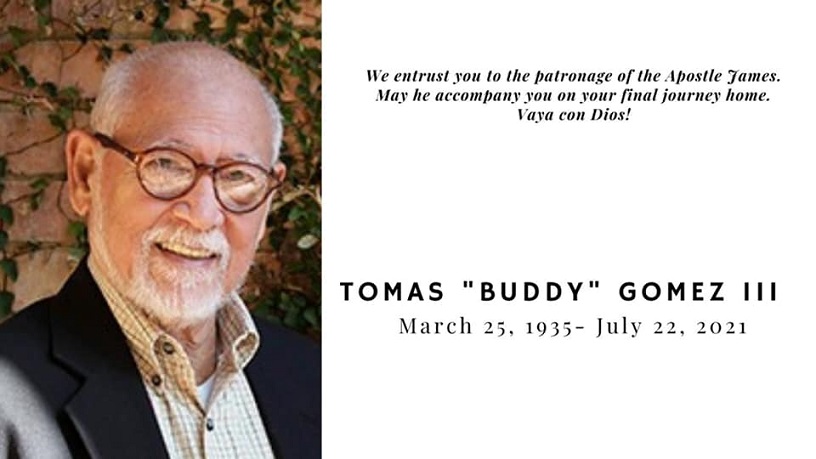

From the Facebook page of Human Rights Commissioner Karen Gomez-Dumpit, Buddy’s daughter.

That was the marvel of social media. Tomas “Buddy” Gomez III and I never had the pleasure of meeting, but we communicated fairly often to exchange views on the state of our country. Albeit separated by the Atlantic, we agreed to embark on what he had thought was a small but momentous mission of unfinished history.

The essential Calbayog-born Buddy Gomez was a retired government official who had not retired from patriotic duties: to unravel more evidence on the Marcoses when they had fled the Philippines in 1986. And that involved sifting through memorabilia he had kept in what he called his “pre-fab house-bodega in the backyard” of his house in San Antonio, Texas, where he was serenely retired.

Buddy Gomez was a point man for the Cory Aquino government. He was appointed in 1986 as consul general to Honolulu, where his primary task was to keep an eye on his most famous constituents, who were, of course, the Marcoses and their fugitive entourage that totaled 89. Aside from nannies carrying boxes of diapers, there were Fabian Ver and family, Eduardo Cojuangco Jr., and dozens of others who identified their destinies with the Marcoses.

In 1990, Cory made him her Press Secretary. He continued to serve under the succeeding Ramos administration. “And then I became an Overseas Filipino Worker,” he would say self-deprecatingly. He worked at various odds and ends in the United States, from hotel front desk clerk to antique furniture restorer.

Buddy recalled a detail about the Marcos escape to Hawaii that the Filipino public had not known. On February 26, 1986, the Marcoses fled the Philippines aboard two C-131 Starlifter cargo aircrafts courtesy of President Ronald Reagan. But the mystery was, the second aircraft arrived at Hickam Air Force Base half a day late. Buddy sifted through newspaper clippings and wrote: “Photographs showed nannies hugging ‘Pampers’ (diaper) boxes. Just a few days later, rumors began to circulate in Honolulu and the world that diamonds and jewelry were secreted within the folds of diapers!

“This was occasioned by news of the arrival of a second C-131 just before midnight, which was also part of the Marcos flight into exile. Initial alarm was raised by the unloading of 22 crates, which contained bundles upon bundles of Philippine 100-peso bills! And that was just for starters! The inventory counted the Philippine currency to be in excess of 25 million pesos, while the certificates of time deposits found in envelopes amounted to 46 million-plus pesos.”

Why was the second aircraft delayed? Buddy and I found a piece of the puzzle from the account of an American friend who lives in Manila today with her Filipino husband. At the time of the People Power revolution, my American friend was in touch with one of the consuls in the US embassy in Manila.

She had related, “Barges were sent to the Palace to bring all those crates to the embassy where they were loaded into helicopters and flown to Clark. As the embassy employees were pushing the crates up wooden boards into the helicopters, one fell off and opened … it was full of gold bars. ” The embassy informed the ambassador who had an open line to Washington. Washington replied, ‘Open all the crates, number them, and make a list of the contents.’ So when they arrived in Hawaii, US Customs had a list of the contents of every crate and item brought with them. One of the consuls present told us this account.”

But what had happened to the inventory the US Customs made of the Marcos cargo? And more importantly: What did they do with the cargo?

“It may have taken the Customs personnel about 10 days to wrap up the inventory and appraisal process. They then issued a confidential document titled: ‘Articles Accompanying Marcos’ Party Upon Arrival, Honolulu on February 26, 1986, per U.S. Customs Service’s Records.’ (This report was ‘done’ on March 10, 1986.)

Altogether, there were about 300 crates/boxes of various sizes to which Customs each appended a ‘Bag Tag number’ with corresponding numbered itemization, followed by description and nomenclature.” The details of these humongous cargo were what he wanted to feast our eyes on. He began sending me encrypted emails, but we had not yet gotten to the main part.

He told me it appeared that the Philippine government of Cory Aquino had already initiated some action before the creation of the Presidential Commission for Good Government. And then the cargo and everything it had was not seized but was released to the Marcoses. Simply said, if the Marcoses left so much data and items behind in Malacañang on the night they fled the Philippines, they had brought much more than they could to Hawaii. And, simply said, that is the reason why they continue to be filthy rich.

In his Cyberbuddy weekly blog in ABS CBN News Online, Buddy, the writer intellectual with the gift of elegant eloquence, warns us tirelessly:

“As we very well know, there is an ongoing shamelessly vainglorious subterfuge to rewrite Philippine history by the remaining Marcoses, with vigorous assistance from the well-financed remnants of that strange ‘Marcos pa rin!’ zealotry.”

There is more in the Buddy Gomez memorabilia in Texas that, someday, historians would love to have their hands on. One of his last concerns only this January was what to do with the cameras of Ninoy Aquino. He was ruminating on where could be its best home. I suggested the Aquino Museum and Library in Tarlac. He had thought otherwise. “The most prominent statue of Ninoy is along Ayala Avenue corner Paseo de Roxas. The Tarlac entity does not enjoy public patronage and may not be cared for adequately. I would rather see Ayala Museum and Filipinas Heritage Library (FHL) become the home of the Ninoy and Cory holdings.”

Apparently, he had more in his pre-fab bodega than just the camera. He cited the Carlos P. Romulo holdings, which had found a niche in FHL. “I will consult Ballsy next time I come home.”

I write all these two days after Buddy Gomez had passed away while he was negotiating the famous Camino de Santiago pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. He died a peregrino in search for the truth. “I go contrite,” he said. “Not with a broken spirit, but with the sincere hope of performing a much-postponed penitence. It has been a long time for penance. It is acceptance of a sinful past, as all must. It is never too late for rueful introspection.” He was 86.

In the meantime, he who did not stop reminding us of the fate of our nation prompts us in this time of our nation’s crossroad: “What is patent, beyond argument, beyond sanity, is that the Marcoses are lying in wait for a political ambush that will finally foist the abnormal veneration of a scoundrel upon a nation they have mercilessly molested.”