Photos by Elizabeth Lolarga

Baguio City lures thousands of visitors during the month of December, many eager to bask in its cool climate and diminishing old-world charm. Where else in the country can anyone enjoy such a clime?

But despite the traffic snarls and rapid urbanization, people still come up for the weekend, treating Baguio as a kind of resort city. But there is more to it than pine trees and flowering sunflowers and poinsettias. The spirit of place is strong, made stronger by its cultural workers and warriors.

On extended run until Jan. 8, 2025 at the basement of the centrally located Baguio Convention Center, “Naked City: Futures from the Crossroad,” the visual arts exhibition that’s part of the recent Ibagiw Creative Festival, indeed strips from the city all those romantic, nostalgic notions and reinstates the significance of the once shunted indigenous peoples and culture.

It felt like the spirit of the late Baguio-born and -based artist Santiago Bose was hovering all over the exhibit area. One sensed Bose’s overall approval.

Curator Rocky Acofo Cajigan did a superb arrangement of the various works of these 23 artists: Andrea Lucido, Bong Sanchez, Dehon Tanguyungon, Eddie de Guzman, Gail Vicente, Jem delos Reyes, John Frank Sabado, Kawayan de Guia, Leonard Aguinaldo, Martin Allama, Mervine Aquino with Benjamin Meamo III, Naidra, Magenta with Faye Olayo, Nona Garcia, Oliver Olivete, Randy Bulayo, Sela Gonzales, Sultan Mango-san, Tommy Hafalla and Zamae Pacleb.

Nothing is sacred from the images of the church (pews, altars, prayer books), an installation of Cajigan, to De Guia’s Statue of Liberty, apparently and deliberately dismembered, the parts spread on the floor and utilizing an assortment of materials like resin, celluloid film, LED lights, laminated grey board and duct tape.

Entitled “Liberty,” De Guia’s collaborative sculpture with Chris Atiwon seems even more resonant as the Donald Trump era enters world affairs next year with its anti-immigrant and other conservative white policies. Social media is rife with images of the disheartened Statue of Liberty crossing the waters from New York to return to France.

De Guia, even in his artistic isolation, preempted those Facebook memes. The weaving of the Liberty parts is reminiscent of intricate Cordillera basketry. The symbol of democracy and capitalism seems to approach an uncertain time of racial discrimination, authoritarianism and the favorable treatment of the economic elite. These thoughts enter one’s head as one circles each part of the fallen Liberty.

The church of Cajigan seems holy on the surface with a hanging high altar and stark pews behind it. If you open the prayer book, what appears are slogans rightfully describing the two dictators whom this country had experienced painfully: Marcos Sr. and Duterte. Tuta, diktador, pasista (puppet, dictator, fascist), the pages read in bold letters.

Although there are liberal elements in the Catholic and Protestant churches, they still remain a minority. The church, even sects like Iglesia ni Kristo, tends to vote for the status quo, and encourage its parishioners to do the same. The artist seems to challenge the viewer to apply one’s critical thinking in approaching institutions that bandy the cross of salvation.

There are two impressive life-size and naked sculptures of a Kalinga couple in the show by Taguyungon. Made of acacia wood, the figures, with painted tattoos on the arms and chest, stand for native nobility. Their nakedness is without any shame. Would that there be more statues of its kind standing in public squares.

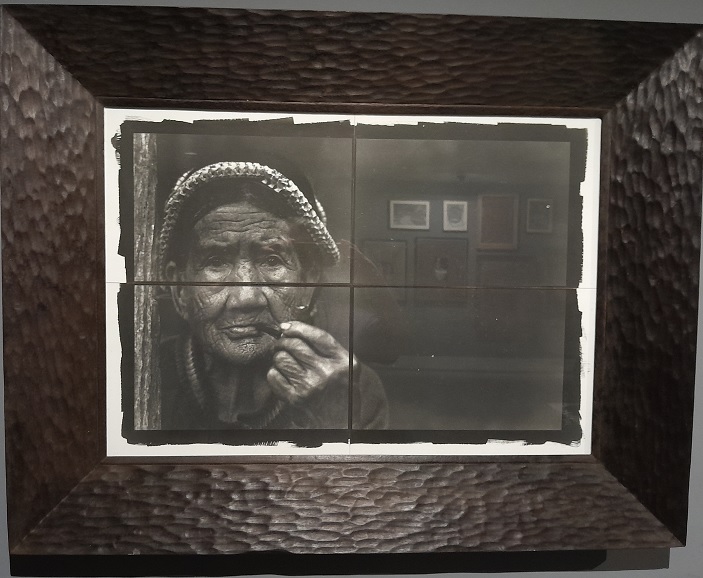

Akin to these noble figures are the black and white photographs of Hafalla, platinum prints on Hahnemule platinum rags. Long ago, he was referred to as the worthy heir of Bontoc’s Eduardo Masferre who, in the earlier 20th century, took photos of the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera, recording their tribal life ways, their clothes, their traditions, their seasons of the year.

Hafalla is not a point, shoot and leave photographer. He immerses himself in communities, and only when he has earned the trust of the elders does haul out his camera and equipment to take group and individual portraits. His subjects look at him directly and frankly with so much honesty. The term goes beyond and above “the noble savage.” There is almost an accusing message in that honesty as though they are daring the viewer to avert his/her eyes from the outward poverty that the looker may assume they live in. They may have been placed in the margins of a cosmopolitan society, but they are the authentic, unbowed Filipinos.

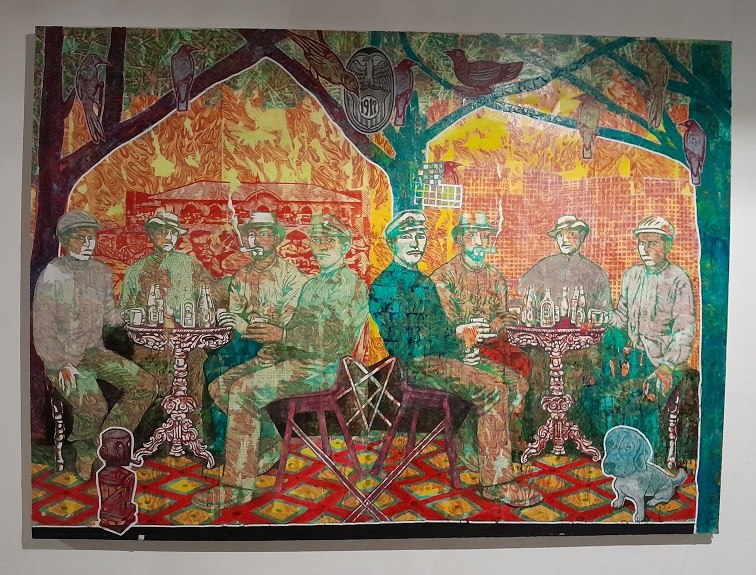

One knows that Aguinaldo has full mastery already of the printmaking processes, but one was not prepared for the splendor of the wall-size (152 x 208.5 cm.) “Fire in the Mountain 1,” a woodcut print executed with acrylic paint, correction tape, pigment ink and collage on canvas. He depicts the stone market builders of the Baguio Public Market, seated and taking five after a hard day’s labor

Like De Guia, Aguinaldo stays relevant what with the question longtime residents are asking: to whom does the market belong? To a big corporation or to the people? Where will the displaced small vendors and suki go once a multi-story mall goes up where the beloved market now stands?

The original builders are shown having a cuppa joe (since one assumes some are the colonialist Americans) or imbibing bottles of gin or smoking cigars. A bulol stands guard on the lower lefthand corner while a cute puppy sits on the right corner, a reference to the dog-eating culture (now outlawed).

This exhibition strips Baguio naked, and one embraces this city, warts and all.

“Naked City” is open from Tuesdays to Sundays, 10 a.m.-6 p.m.