By IGAL JADA SAN ANDRES

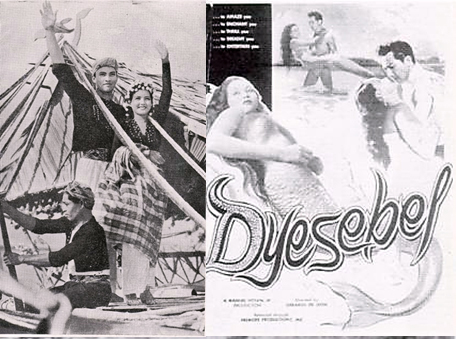

(Photos from Nick Deocampo’s personal collection)

THREE days before his last research stint as a senior Fulbright scholar at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. ended, Nick Deocampo made a stunning discovery that should have shaken the Philippines.

THREE days before his last research stint as a senior Fulbright scholar at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. ended, Nick Deocampo made a stunning discovery that should have shaken the Philippines.

That year, 2003, he chanced upon Zamboanga, a 1936 film produced by Americans Eddie Tait and George Harris for the US market. Considered lost since its screening in San Diego, California in 1937, it is the oldest of five feature-length films that survived the razing of Manila during World War II.

Alas, films such as Zamboanga are lost these days in the whirlwind of society’s insistence on the hip and the new, pushing aside the ancient into a dark corner where, perhaps, they’ll remain indefinitely.

But for Deocampo, who is on a mission to write five volumes about the country’s film history, the past is a part of the present. And it was during his quest for historical knowledge that he started to build his film collection.

‘Esoteric’

“It’s quite an extensive one,” Deocampo said of his personal collection. “(T)hese are films that are not in anybody else’s collection. It’s quite an esoteric collection that I have.”

Copies of American newsreels made at the height of the Filipino-American War in the late 19th century (such as Advance of Kansas Volunteers at Caloocan by Thomas Edison’s studio), Filipino films made during the Golden Era of the 1950s (including fragments of a komedya-inspired film called Banga ni Zimadar), films made on contract by Filipino directors like Lamberto Avellana and Teodorico Santos for other countries, and the early independent films of the 1980s comprise his collection.

Included also are his own documentary films, such as Oliver and Revolutions Happen like Refrains in a Song. “I should be the first collector of my own films,” he said.

Most of the films in Deocampo’s collection were reaped from his work as a historian.

“I turn all opportunities that I have when I go abroad or when I travel in various islands in this country to look for films,” he said. “Or to drop words, for example, that, ‘I’m looking for certain films in aid of the research that I do.’”

In fact, Deocampo is leaving in March for Ann Arbor, Michigan to, he hopes, bring home a copy of the 1914 film Native Life of the Philippines by Dean C. Worcester, the first Secretary of State in the country. The film is celebrating its centennial year of production this year.

Should he accomplish this mission, he would be bringing home one of the oldest films to date in his collection.

In addition, the impression that Worcester left on the Philippines is a primary reason Native Life of the Philippines is important.

“(This film) was so controversial because it was used by Worcester to, in fact, campaign against the independence of the Philippines,” Deocampo said. “All the way to Cebu I dig up accounts, for example, of how he was lambasted and hated by many of the Filipinos, and people called him the ‘Ugly American’ because he made use of film to, you know, really go against the desire of the Filipinos to become independent.”

Worcester’s efforts to derail the Filipinos from attaining independence were not lost on the media. Throughout the time he spent as secretary of the interior, journalists had been accusing him of misusing his position. It was, however, in 1908 that the blow really came.

El Renacimiento (The Rebirth), a newspaper known for its critical stance, published an editorial written by Fidel Reyes titled “Aves de Rapiña (Birds of Prey).” The article charged an American official with exploiting the country’s resources for personal gains. Although his name was not brought up, Worcester strongly felt alluded to and subsequently a libel suit against the newspaper’s staff, including Reyes, editor Teodoro Kalaw and publisher Martin Ocampo.

The case lasted for several years, and eventually ended with Worcester winning.

Deocampo is the first to acknowledge that he is not an archivist, which is why he is willing to turn over his collection to the recently created National Film Archive of the Philippines.

“I don’t even call myself an archivist; I’m just a collector and…a researcher. I’m just an accidental archivist and, that’s why when I started smelling the vinegar syndrome of my films—some of the films, including Dyesebel, were already melting—(I decided that) this is the time to turn over my documents, my collection, to the state,” he said.

Four approaches

For Deocampo, every film is significant.

Drawing upon years of research, he said, “Every film is historically significant, even if it is Pido Dida. I can analyze that film and, at the same time, enlighten ourselves of the Cory Aquino days. Why was Pido Dida released during that time?”

In his classes at the University of the Philippines Film Institute, Deocampo uses four approaches to the study of film history: film is history, film as history, history can be found in film, and the relationship between film and history.

“(T)he whole notion of film as entertainment only works best really when it is first released. After that, I feel that its historical value is like a painting; it increases even if it’s the most commercially produced film,” he said. “Every film, for me, is significant. So I don’t have any bias at all whether the film is a classic, which is invented—that value is invented—or it is commercially released.”

Government intervention

But, perhaps, like other institutions of the arts, film in the Philippines is suffering from neglect.

Badlis sa Kinabuhi, for instance, a 1969 Cebuano film Deocampo had been actively campaigning for preservation, had lost its sound when the authorities finally intervened. There are no surviving Cebuano films from that era.

“Can you just imagine that? How much we’ve lost?” he lamented. “It’s like a lost language.”

Film, Deocampo said, can also be a victim of political turmoil, which is what happened to the first Philippine film archive set up in 1982 by then First Lady Imelda Marcos. The struggle for political power that followed affected the institution.

“So what happened to the collection? Nada. I was right beside the first archivist, Ernie de Pedro, and he was talking lengthily about that period and how all the films were lost because of the political wranglings that happened,” he said.

But, today, this film historian hopes that the dream of every film enthusiast would come true with the opening of the National Film Archive of the Philippines in Cubao, Quezon City.

150 titles more

In Deocampo’s possession is a list of 150 titles of films made in and about the Philippines from 1898 to 1942. “Not that I’ve found everything, but I know the source. I have located where they are,” he said.

Most of these are located abroad where archival technology is vastly superior to the Philippines’. “Archives are expensive and technological,” Deocampo said. “You have to maintain a certain temperature.”

After producing and directing films in the Philippines, Westerners also brought their works back to their home country to be screened.

“The beautiful thing is that they are required by law to furnish the state or the federal archive copies of the film. Other than that, there are private collectors, which is why they were able to preserve films,” Deocampo said.

Philippine films were also marketable in other countries, just like today’s surge of Korean pop culture in the country, he added.

Deocampo said: “Right after the war, the Big Four rose: LVN, Sampaguita, Premiere, Lebran. All of them were technically equipped…because Hollywood immediately flooded our markets with technology, with movie houses, with movies.(W)hile the other Southeast Asian countries were just recovering from war, in less than five years the movie houses (in the Philippines) were already up and bouncing with business.”

Chinese distributors would buy the films and sell them to other Asian countries, especially in the Mekong region where, Deocampo said, “most of our films were found and could be found.”

“If I only have a budget right now, I would travel to the Mekong countries and I’m sure I’ll find Filipino films there,” he said.

Lack of resources, a constant bane of being a researcher, is a major reason Deocampo has been able to bring only a few of these films back to the Philippines.

“If we only have the budget to look through all the archives, including personal collections, my goodness me,” he said. “I want to bring home all those 150 titles (but) I can only bring home one by one, one by one.”