Today, Philippine artisanal salts remain a niche product, an expensive one. And for those who actually buy it, it is considered as a chef’s delight, a gourmet pasalubong, or a foodie’s choice.

Do get and enjoy some our artisanal salts, while it is still around.

Asin tibuok (Bohol)

Bohol’s sea salt moulded in a clay pot is called asin tibuok, meaning “unbroken or whole salt,” from the town of Alburqueque. Asin tibuok used to be bartered, with one asin tibuok for two gantas or four kilos of rice. A Jesuit priest, Fr. Ignacio Francisco de Alcina described this type of salt making in his 1668 account of the Visayan people.

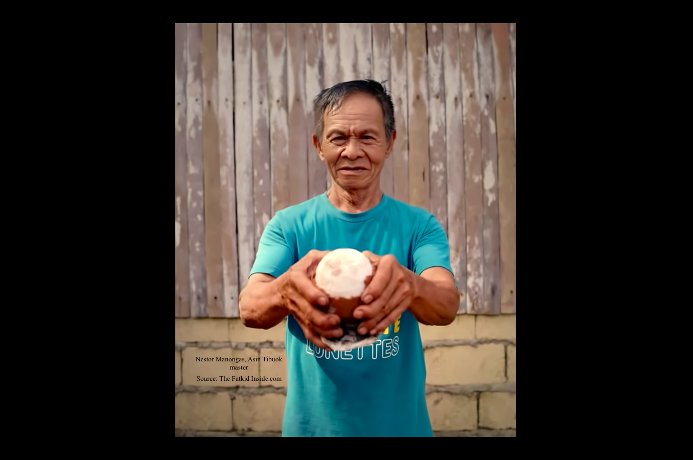

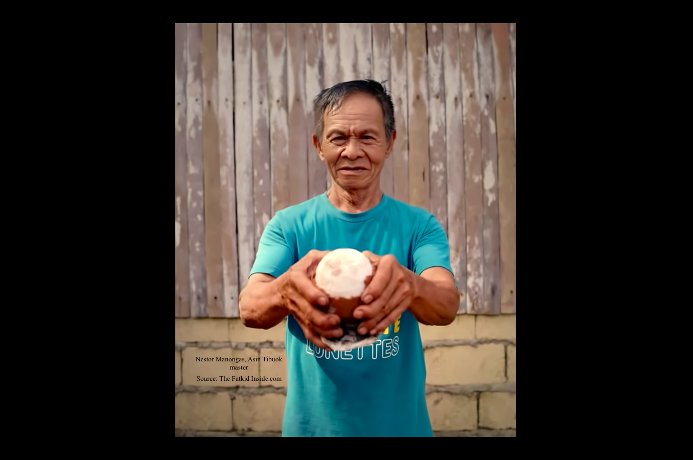

It is reported that only two families make asin tibuok in Alburqueque. One of them is Nestor Manongas, in his mid-70s, with no successor in sight.

Asin tibuok is included in the Slow Food Ark of Taste, a catalogue of endangered heritage food around the world maintained by Slow Food International. An enterprising Filipino-American has been exporting asin tibuok and other Philippine food products to the United States, where it is known as “dinosaur egg.”

Making asin tibuok

Salt-makers gather dried coconut husks and place them in a salt pond (paril) where they are soaked in saltwater from three to six months. Then, the husks are sun-dried, broken into smaller pieces, and burned into ashes that lasts around four days. During this time, the fire is controlled; it is not allowed to go out and sprinkled frequently with seawater. Somebody has to watch the fire the whole time. The resulting ashes are white (gasang) and placed in a large cone-shaped funnel made of bamboo and buri leaves (sagsag). Seawater is poured continuously into the funnel. Another container catches the filtered brine from the funnel. Filtering is done at least three times using different funnels to get a concentrated brine solution.

Nestor Manongas, Asin Tibuok Master. Source: The Fatkid Inside.com

The brine is transferred into clay pots called kun (short for kulon) that serve as moulds and cooked in an open-pit fire. Local female potters make these clay pots, using the paddle-and-anvil technique.

Continuous heating and boiling of the clay pots for the brine to evaporate is done the whole day. When the bottom of the pot cracks, it is done and cooked, with a hardened salt inside the pot.

Tultul (Guimaras)

Barangay Hoskyn, Guimaras Island in Iloilo is the source of tultul, salt blocks made in limited quantity by Serafin and Emma Ganila, following their own family tradition.

First, driftwood is gathered along the shore, which is burned and its ashes are placed in baskets or kaing in an elevated bamboo platform; seawater is poured into each kaing. A pail is placed under the kaing to catch the liquid, a brine solution. The brine is transferred into several tin containers, usually cooking oil cans. Coconut milk is added into the brine, to make it savoury. It is boiled in an improvised outdoor stove for six hours until the mixture hardens. After cooling, the hardened salt is removed from the can, and chopped into smaller pieces for selling. Tultul, as a viand itself, is eaten with rice.

Asin sa buy-o (Zambales)

Buy-o is the name for a cylindrical container made of woven nipa used to pack salt produced in Botolan, Zambales. The nipa leaves are cut off from the palm and sewn together to form a wide sheet, and formed into a cylindrical shape.

First, sand is collected into a large mound; seawater is poured on the sand to saturate it with salt, and dried the whole day. The sand is dumped into a large wooden funnel, and seawater is poured once more and at its bottom is a large cooking vat or kawa. The strained water is boiled continuously and the funnel is topped with more seawater. Sea salt is formed in the vat, collected, and dried. Finally, the salt is packed tightly into the buy-o container.

Budbud (Miag-ao)

Budbud means “to sprinkle” in Hiligaynon. Budbud salt is harvested from elevated and large bamboo poles, split lengthwise, and laid under the sun. First, an area in the beach is prepared, cleaned of debris, and raked. Then, large bamboo poles are used to collect seawater that is sprinkled over and over onto the sand for several days. The sand becomes saturated with salt from the seawater. The sand is shoveled into sacks and carried into a holding area. Again, seawater is poured into the mound of sand, which drains the brine into a holding area. Extracts of a vine called balunos is mixed into this liquid. The brine is transferred into the cut bamboo poles lying under the sun. When dried, large particles of salt are formed. Only women, using a special bamboo scraper, harvest the budbud salt.

An archipelago surrounded by the sea, the Philippines has a strong salt-making tradition, historically. And yet, it imports today around 80 percent of its salt, mostly from Australia and China. Insane, isn’t it?