By NORMAN SISON

WOULD you get married at a centuries-old cemetery? That may sound macabre, but couples who get hitched at Paco Park in Manila do just that.

Weddings are about living happily ever after till death do they part. So, the usual venues are beaches, gardens, poolsides and other romantic places. After all, you’d want to have lasting memories when you flip through your photo albums.

Couples tying the knot at Paco Park think the place is a garden with its towering old trees and walled coziness of a park. Its thick adobe walls exude the old-world charm of a bygone era while keeping out the rumble of present-day motor vehicles.

Burials there ceased in 1912. Most of the niches in those walls are now empty and sealed up.

But it’s still a cemetery. There are still 65 people interred in those lovely adobe walls, including 22 children. One of Paco Park’s oldest residents is one Dorotea Mateo, who died on August 14, 1882.

All of the grave markers or lapidas are in Spanish, a testament to a time when Spanish was once the Philippines’ official language until American colonial rule brought in English.

Paco Park is about two kilometers from the ancient Spanish quarter of Intramuros, the original Manila. A map dated 1898, kept in the archives of the Lopez Museum, shows Cemeterio de Paco to be in what was then a suburb of Manila.

It was originally meant for the affluent and aristocratic Spaniards who resided in the walled city. Cemeterio de Paco was inaugurated on April 22, 1822. In 1859, Spanish governor-general Fernando de Norzagaray ordered the cemetery expanded. The outer wall was built, bringing the cemetery to its present 4,100 square meters.

Centuries of urbanization and the march of time have swallowed up Paco Park, making it appear lost in a concrete jungle. It would’ve totally faded from memory if it weren’t for history.

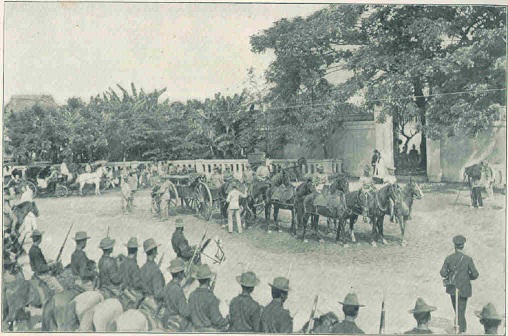

A US Army general was once buried there. Major General Henry Lawton was killed on December 19, 1899, in the Battle of San Mateo and temporarily interred at Paco Park before he was transferred to his final resting place in the United States. He was the highest ranking US military officer to be killed in the Philippine-American War (1899-1902).

But Paco Park’s place in history was assured decades before Lawton’s death. The park is the final resting place of three Roman Catholic priests – Mariano Gomez, Jose Burgos and Jacinto Zamora — who were executed in 1872 for alleged sedition by the Spanish colonial authorities. However, they were buried in a common grave, not in the walls.

The three priests are known in Philippine history books by the acronym Gomburza.

Among the hundreds who witnessed the triple executions at a promenade outside Intramuros — Luneta, present-day Rizal Park — was future Philippine national hero Jose Rizal, then only 10 years old. That day of February 17, 1872, according to the late Filipino historian Nick Joaquin, “marked the beginning of a nationalist consciousness.”

Their deaths, Rizal wrote, “awakened my imagination, and I vowed to devote myself to avenge such victims some day.” In 1891, Rizal dedicated to his second of two nationalist novels, El Filibusterismo, to the memory of the three priests. “Gomburza” was a password used by the Katipunan revolutionary movement.

Their deaths, Rizal wrote, “awakened my imagination, and I vowed to devote myself to avenge such victims some day.” In 1891, Rizal dedicated to his second of two nationalist novels, El Filibusterismo, to the memory of the three priests. “Gomburza” was a password used by the Katipunan revolutionary movement.

On December 30, 1896, Rizal himself was buried at Paco Park following his execution at Luneta for allegedly masterminding the Philippine Revolution, which broke out earlier that year. He was buried in an unmarked grave to prevent his body from being used as a rallying point by Filipino revolutionaries.

One of Rizal’s elder sisters, Narcisa, found her brother after days of searching other cemeteries. She had a marble slab placed on the freshly dug grave. Inscribed on the slab were the letters “R.P.J.”, Rizal’s initials in reverse.

In 1898, Narcisa had the body exhumed and found her brother, without a coffin, still in his recognizable black suit. The remains stayed at Narcisa’s Binondo home in an ivory urn until 1912 when Rizal was reinterred at his final resting place, Rizal Park. Today, manicured grass, a cross and a bust mark the spot, enclosed by a fence, where Rizal was originally buried at Paco Park.

Aside from weddings at the Chapel of Saint Pancratius, Paco Park is popular with photography artists and sweethearts. In the 1980s, it was even a venue for a televised classical concert series known as “Paco Park Presents”.

Visitors take photos at the main gate, which gives the feeling of entering a portal going back in time, although pop music from an FM radio station blares from outdoor speakers, jarring the park’s atmosphere of old-world tranquility.

Even more irreverent is a toilet sign placed near a common grave, marked by a tall cross, just a few meters from the gate. Never mind that it is the final resting place of the Gomburza priests.

Of course, considering its long history, people expect Paco Park to have its share of ghost stories. A security guard says the women’s toilet is reported to be ground zero.

One woman relates that a door of one of the three cubicles closed shut while she was washing her hands. “I knew that I was the only one there,” she says. “I just pretended that nothing happened, but actually the hair on the back of my neck was standing on end.”