By JAKE SORIANO

DIVINA is preparing for her daughter Rowena’s 13th birthday when she hears shocking news: her daughter has been attacked by a crocodile, her body still missing. As Divina searches for the body of her daughter in the marshlands of Agusan del Sur, she learns a lesson more tragic than her fate: not all predators are underwater. The film is based on actual events.

DIVINA is preparing for her daughter Rowena’s 13th birthday when she hears shocking news: her daughter has been attacked by a crocodile, her body still missing. As Divina searches for the body of her daughter in the marshlands of Agusan del Sur, she learns a lesson more tragic than her fate: not all predators are underwater. The film is based on actual events.

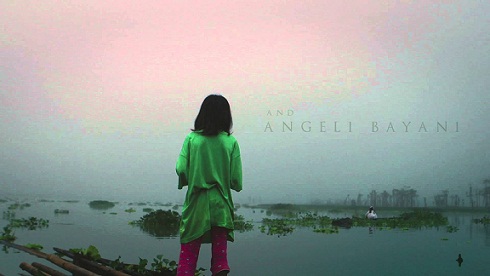

That’s the promotional blurb of Francis Xavier Pasion’s Bwaya (crocodile), one of the entries in the 2014 Cinemalaya closing on Sunday.

One recalls a 1988 movie, A Cry in the Dark, starring Meryl Streep in a true-to life story about a mother’s (Lindy Chamberlain’s) quest for justice when she was accused of murdering her nine-month-old daughter while on vacation in Australia’s Northern Territory. The baby was taken out of their tent by a dingo, a wild dog.

That’s where Meryl Streep, in Australian accent, famously uttered :”The dingo’s got my baby!”

In Bwaya, a crocodile ate Angeli Bayani’s daughter.

Between Streep in A Cry in the Dark and Bayani in Bwaya, it’s really no contest. Bayani wins the imaginary smackdown. And in Bwaya Bayani speaks in dialect too, accent and all, in a performance that, had Streep seen it, she would have been compelled to call her agent immediately, demanding the lead role in any future film to be shot in the marshes of Agusan.

Bayani is a cinema gem. In performance after performance, she has never failed to dazzle and stand out – from her minute-long reporter role in Joel Lamangan’s Filipinas to her star-making turns in Lav Diaz’s eight-hour Melancholia, six-hour Siglo ng Pagluluwal and the short Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan which only runs for four hours.

Bayani is a cinema gem. In performance after performance, she has never failed to dazzle and stand out – from her minute-long reporter role in Joel Lamangan’s Filipinas to her star-making turns in Lav Diaz’s eight-hour Melancholia, six-hour Siglo ng Pagluluwal and the short Norte, Hangganan ng Kasaysayan which only runs for four hours.

Already, Bayani has created an entire universe of varied and sublime characters. Her performance in Bwaya only expands this universe further. Her role as Divina gives her a wide space for showing off her talents, and show them off she does.

It is a role crafted with immense care by the complementary skills of Bayani as actor and Pasion as director. Pasion is a radical realist, a convincing progeny of such radical realists as Abbas Kiarostami and Michelangelo Antonioni. Like them, Pasion challenges notions of cinematic reality as naturalism; for him the representation of this reality always includes himself as filmmaker.

Bwaya is therefore not a film that mixes the real from the performed, despite the presence of both acted scenes and documentary footage featuring the real Manobo couple who lost their daughter to the crocodile. What the film offers, when taken as a whole, is a crucial insight not only into grief but also into cinema itself.

Pasion understands the strangeness of his setting and the strangeness of his presence in the place. He is aware that he is not an observer here. To silently observe and hide his presence is a myth, and he must break this myth down if he is to set himself apart from others, like him bringing with them their cameras, who have called on Divina and her family to try and “document” her story.

Bwaya presents grief not as a state of being but as something that is done. Something that is performed.

Divina grieves, not in the privacy of her home but in the community school, in full view of the members of her community. They are her audience; she performs for them.

Bayani’s performance here is a masterwork of both deceit and sincerity, of the surface meeting great depths. The contortions of her body are a glorious feat of artistic gymnastics. And that face. Angeli Bayani is our Garbo, our Falconetti.

“Bwaya” is currently screening in CPP and in select theaters in Metro Manila as part of this year’s Cinemalaya Film Festival. Schedule of screenings may be found at the Cinemalaya website.