By YVONNE T. CHUA

By YVONNE T. CHUA

(Infographics sourced from OECD report)

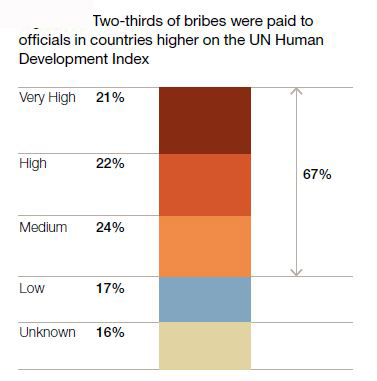

CONTRARY to popular belief, corruption isn’t the scourge solely of developing countries like the Philippines.

In fact, two-thirds of bribes paid by businesses to foreign public officials took place in countries with medium to very high human development index, including the most developed economies, says a report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on foreign bribery released Tuesday.

“Bribes are being paid across sectors to officials from countries at all stages of economic development,” according to the OECD Foreign Bribery Report, the first of its kind.

“Bribes are being paid across sectors to officials from countries at all stages of economic development,” according to the OECD Foreign Bribery Report, the first of its kind.

The report analyzed 427 foreign bribery cases law enforcers in 17 countries have successfully concluded since the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions came into force on Feb. 15, 1999.

Forty-one states have signed the convention, which makes bribery in international business a serious crime.

The convention defines foreign bribery as “to offer, promise or give undue pecuniary or other advantage, whether directly or through intermediaries, to a foreign public official, for that official or for a third party, in order that the official act or refrain from acting in relation to the performance of official duties, in order to obtain or retain business or other improper advantage in the conduct of international business.”

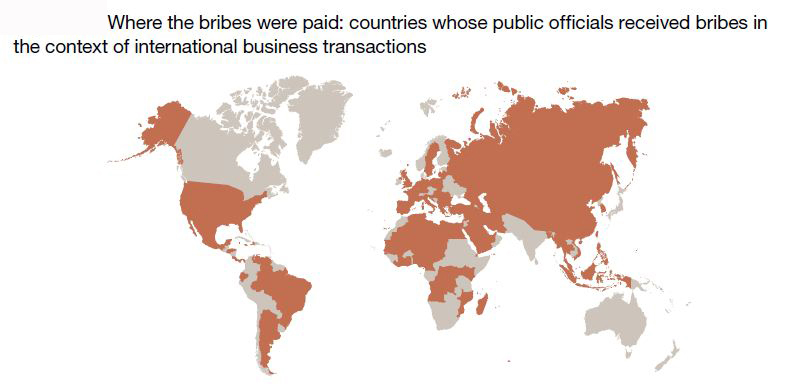

The OECD report, which probed the who, what, why, where and how of foreign bribery, identified the Philippines as among 11 countries in Asia where public officials received bribes in international business transactions and became the subject of investigations under the OECD’s anti-bribery convention.

Other Asian countries listed in the report were Bangladesh, China and Chinese Taipei, India, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, Mongolia, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam.

The report, which aims to measure the “covert and complex crime” in a bid to step up the fight against transnational bribery, did not supply details of the cases in Asia and in 74 other countries, save for those with the longest prison sentence (13 years on a U.S. congressman), the highest combined fine against a single company (1.8 billion euros), and the highest amount forfeited by an individual ($149 million), among others.

Allegations of foreign bribery have rocked the Philippines in recent years. In 2007 the National Broadband Network deal was canceled following charges of corruption in the awarding of a $329 million contract to China’s ZTE.

The Czech ambassador to the Philippines has accused Metro Rail Transit officials of trying to secure a bribe from a Czech company for expansion of the rapid transit system traversing EDSA.

The 45-page OECD report found that bribes were paid to corner public procurement contracts in 57 percent of the cases and clear customs procedures in 12 percent.

The 45-page OECD report found that bribes were paid to corner public procurement contracts in 57 percent of the cases and clear customs procedures in 12 percent.

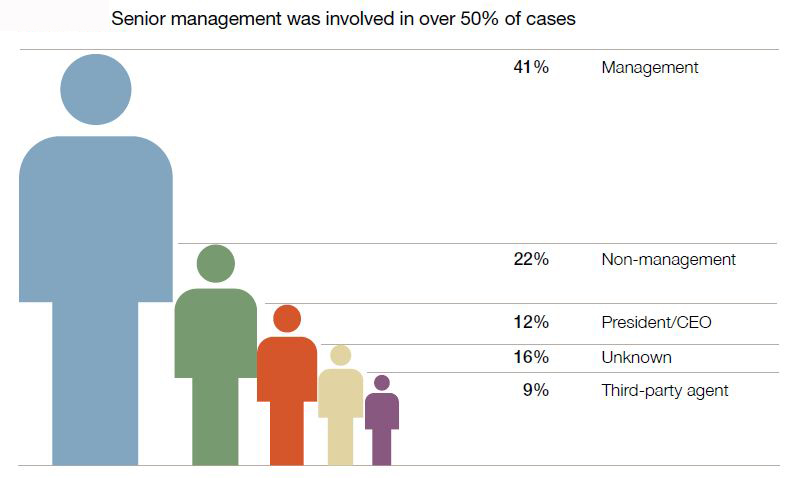

Three of five companies whose representatives bribed foreign public officials were large firms with more than 250 employes, it said.

In more than half the cases, corporate management, including the CEO, paid or authorized the bribe, according to the report. This finding, it said, shatters the “rogue employee myth” and raises the need for a “clear ‘tone from the top’” in enforcing corporate anti-bribery policies.

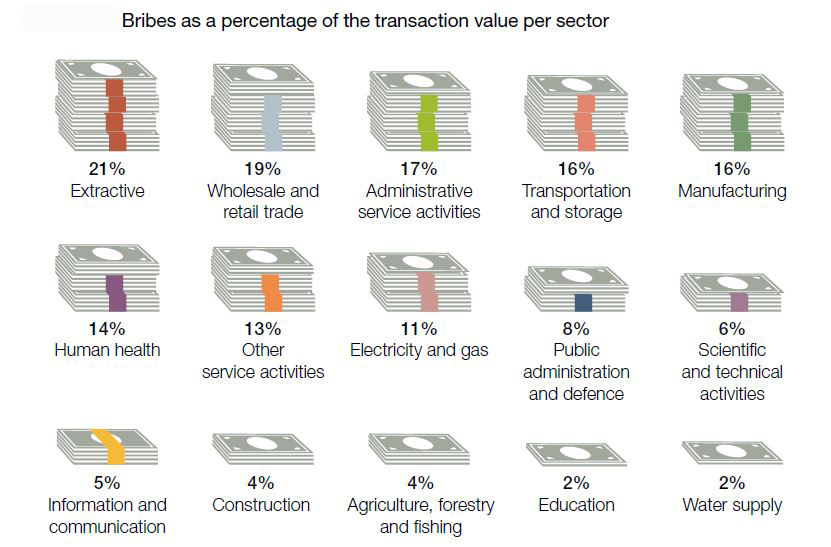

Two in three of the foreign bribery cases took place in four sectors—extractive, 19 percent; construction, 15 percent; transportation and storage, also 15 percent, and information and communication, 10 percent.

The report said bribes were coursed through intermediaries in three out of four cases. Of these, 41

percent of went through agents such as local sales and marketing agents, distributors and brokers, and 35 percent through “corporate vehicles” that include subsidiary companies, local consulting firms, companies in offshore financial centers or tax havens or companies formed for the public official who got the bribes.

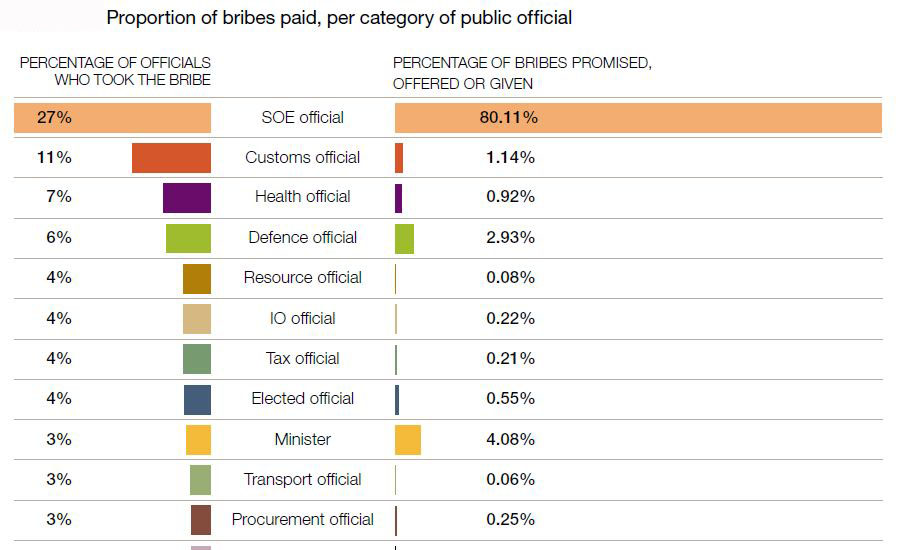

The bribes equaled an average of 11 percent of the total transaction value and slightly more than a third of profits, and were pocketed by those in state-owned enterprises (SOE) in 27 percent of the cases and by customs officials in 11 percent, the OECD said.

The bribes equaled an average of 11 percent of the total transaction value and slightly more than a third of profits, and were pocketed by those in state-owned enterprises (SOE) in 27 percent of the cases and by customs officials in 11 percent, the OECD said.

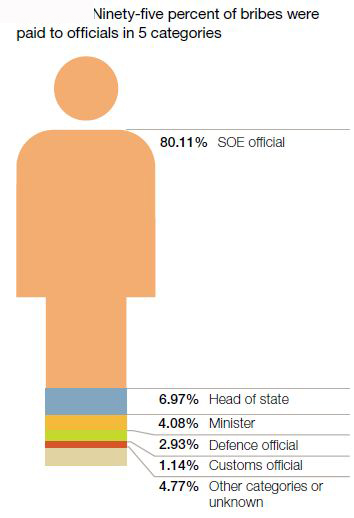

Officials of state-owned companies ranged from the CEO or president, to management, and even lower-level employees, who in all interestingly received 80.11 percent of total bribes, the report showed.

Although heads of state and ministers were bribed in only 5 percent of cases, the OECD said they nevertheless received 11 percent of total bribes. In contrast, customs officials were bribed in 11 percent of cases but received only 1.14 percent of total bribes.

“This could confirm a preconceived notion that the more powerful the official, the more s/he receives in bribes,” the report said.

According to the OECD, one in three cases came to the attention of law enforcers through self-reporting, or defendants voluntarily disclosing their involvement in foreign bribery, often after this was uncovered in internal audits or due diligence during mergers and acquisitions.

The report also said the police, customs and border protection authorities, as well as mutual legal assistance between countries, brought a significant number of cases to light.

But only a small number of cases came about because of media coverage and investigative journalism (5 percent), and of internal or third-party whistleblowers (2 percent).

The OECD report noted that the media remain “an important untapped source of information.”

It, meanwhile, urged “strong and effective” mechanisms to protect whistleblowers in both the public and private sectors, as well as encourage and enable employees to report corporate misconduct without fear of reprisals.

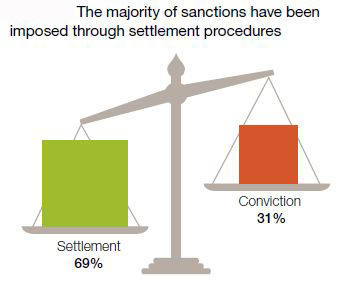

Of the 427 concluded cases, the report found that 69 percent ended in settlement and the rest in conviction.

Of the 427 concluded cases, the report found that 69 percent ended in settlement and the rest in conviction.

Civil or criminal fines were imposed in 261 cases, confiscation in 82, and imprisonment in 80, it noted.

Civil or criminal fines were imposed in 261 cases, confiscation in 82, and imprisonment in 80, it noted.

The OECD anti-bribery convention requires states to confiscate the instrument of the bribe and its proceeds or property of equivalent value.

But the report explained the low proportion of confiscation in the 427 cases: “(I)n many cases the company or companies involved paid ‘disgorgement’ or had the proceeds of the foreign bribery confiscated, whereas the individuals in questions were either fined or received suspended or actual prison sentences.”

In the report’s preface, OECD Secretary General Angel Gurria said collective action by governments, business and society is needed to “win the war against corruption.”

“The corrupt must be brought to justice; the prevention of business crime should be at the center of corporate governance policies; and public procurement needs to be synonymous with integrity, transparency and accountability,” he said.