Traditional baskets are familiar objects that we do not give them much thought. Until one bilao was advertised as a rustic art décor for US$ 299 by an international furniture company, and the news went viral. Indeed, an arty price for an ordinary bilao!

Nowadays, the bilao is usually used as a takeout and throwaway container for pancit or kakanin or rice cakes. Its original function as a winnowing tray, separating rice from its chaff and dirt, may have been almost forgotten in Metro Manila.

Rara or lala

Aside from weaving cloth, the Philippines has a strong tradition of weaving leaves and vines into baskets and mats, known as rara or lala. Plants that grow wild and abundant such as tikug, nito, bamboo, rattan, coconut, pandan, buri, anahaw, abaca, seagrass, and water hyacinth are used for making baskets.

Weaving communities are found all over the country, especially among the indigenous peoples such as the Ifugao, Kalinga, and Ibanag in Northern Luzon down to the Bilaan in Southern Mindanao, and the Tausug and Sama in Tawi-Tawi, Sulu.

These communities also possess the knowledge of local plants, the right time to harvest, and the processing and treatment needed to make baskets pliable and durable. In many ways, our poorest communities are the biocultural caretakers of these natural resources.

Multiple uses

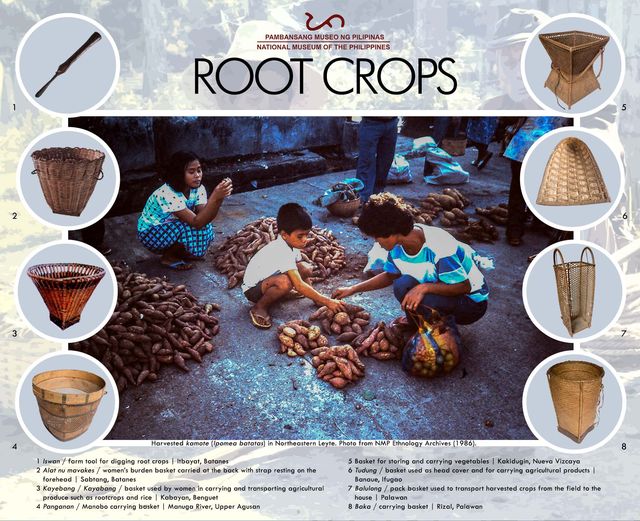

Bamboo and rattan are the most commonly used materials in making baskets that come in a variety of shapes and sizes, depending on use. Notably, each basket type has its own specific local name and use, according to locality.

In a house, clothes and blankets are stored in a rectangular basket with a lid (tampipi).Small bags are for tobacco or for betel nut chewing. For sleeping, there are mats and for a baby, a cradle (duyan).

In the kitchen, there is a basket of rice for cooking, a woven sieve (bistay), or even spoons. A bilao or kararaw is for cleaning the rice before cooking. Salt is stored in a basket. Some baskets are tightly woven and waterproof for storing water, tuba, or rice wine. Under the house, woven chicken coops are hung to keep them safe.

Basket containers are used mostly with rice such as holding seedlings while harvested rice is stored in baskets inside or under the house. Tambobong is a Tagalog word for large bamboo containers for storing rice.

Palay or corn is dried under the sun in sawali or amakan, woven split bamboo mats. They are also used as walls or ceilings of a house.

Carrying baskets

A primary function of baskets is to transport objects, mostly agricultural produce. Baskets (kaing) serve as containers of crops (rice, corn, sweet potatoes, fruits, and vegetables) from the fields to the houses and markets and generally carried on the head, back, arms, and shoulders.

In Ifugao, tupil is a lunchbox for carrying cooked rice in the field. There are special baskets for pork meat after a hunt, or for locusts; another basket called agawen is worn at the hip, for collecting snails in the rice paddies. A popular Cordillera bamboo-and-rattan backpack, pasiking, is a practical container for almost anything.

For protection against the elements, there are hats and raincoats. In Batanes, vakul is a raincoat for women as well as slippers made of abaca, both waterproof.

Fish traps

Fish traps (bubo) made of split bamboo, with narrow openings and a one-way trap door, are also made, based on traditional knowledge. Their size and shape depends on the type of marine animal (fish, shrimp, crab, eel) to catch as well as its environment, such as water depth, current, and underwater features.

In the Ilocos region, the barekbek is a cylindrical bamboo fish trap usually set in rivers. Another one is called pamurakan one of the largest shaped like a hammock, and almost three meters in length. It is submerged open side up in brackish water and filled with twigs and leaves where fish would shelter and hauled out after a month or two.

Recognition and challenges

As a source of livelihood, making baskets is usually learned from parents and older relatives, starting from a young age. Such knowledge is also transmitted by making baskets in a communal setting, learning from others, and being mentored by a traditional master weaver.

Today, basket-making communities face dwindling natural resources, the widespread use of plastics, the decreasing interest among the younger generation to learn the craft, and the changing demands of the market.

The National Museum of the Philippines in an online exhibit titled, Entwined Spheres: Baskets and Mats as Containers, Conveyors and Costumes, shows the craft and artistry of baskets that reflect the “identity, politics, kinship, gender, socio-economic status, and religion” of weaving communities in the country.

Most importantly, the exhibit honors Filipino weavers and how their practices of basket and mat weaving “help create and set tangible representations” of Philippine culture and heritage.(See: http://pamana.ph/ncr/manila/NMA360.html)