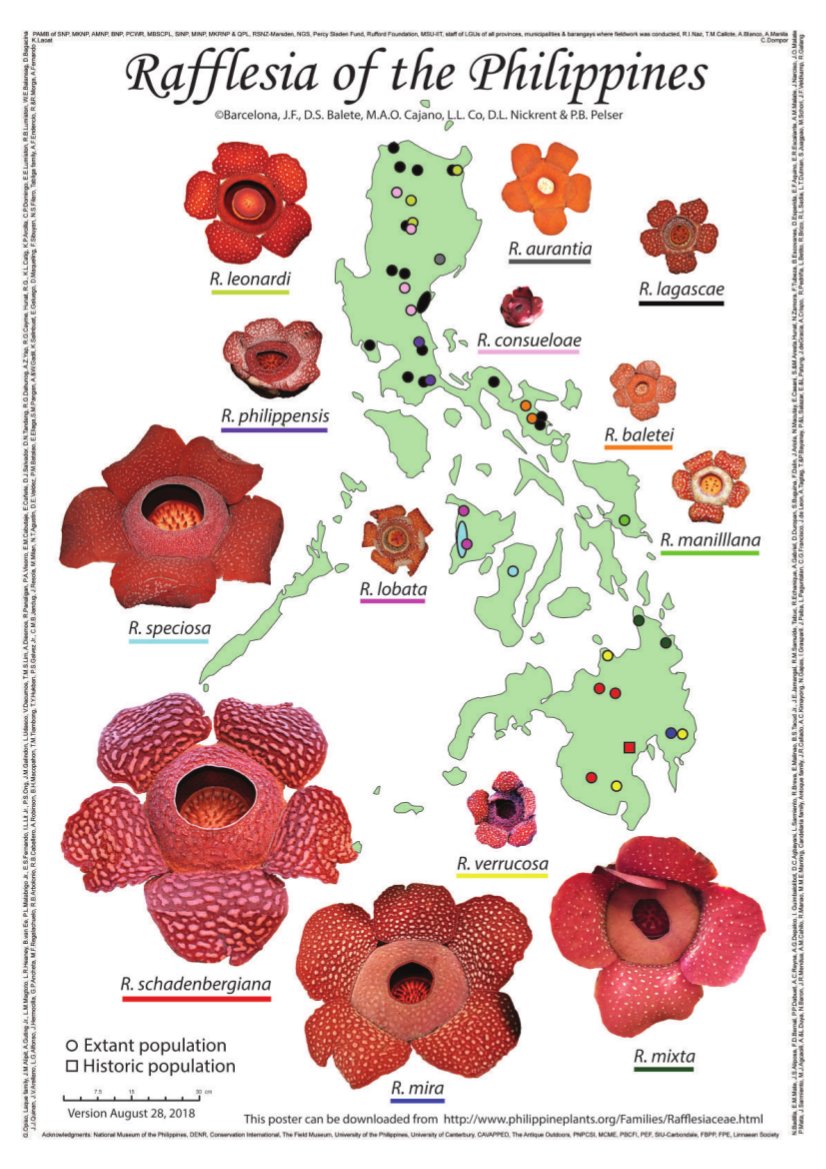

One of the centers of Rafflesia diversity, the Philippines has 13 currently recognized species found only in five larger islands—Luzon, Samar, Panay, Negros, and Mindanao.

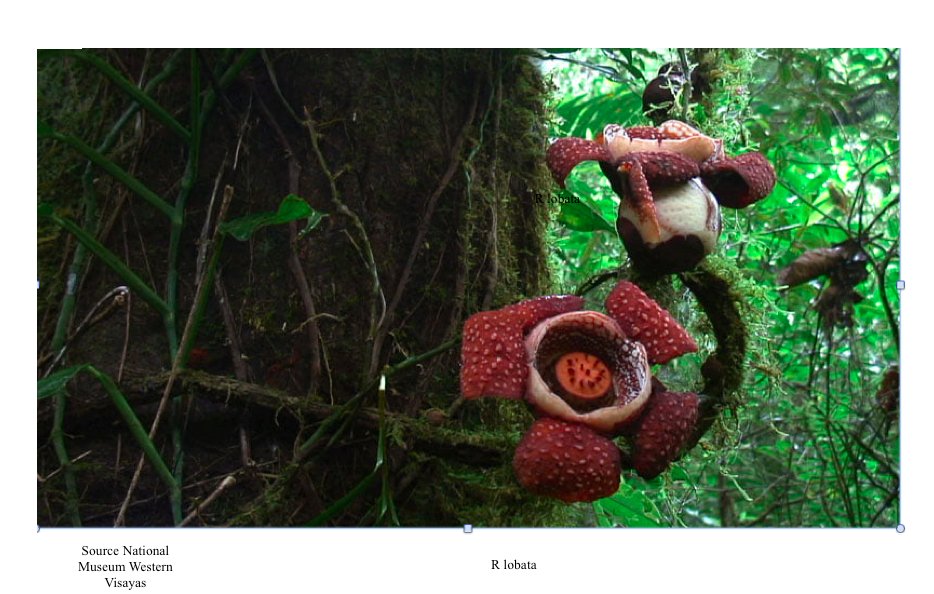

Three species— R. manillana, R.speciosa, and R. lobata —are found only in the Visayas, in Panay and Negros. R. speciosa is called urùy, kalò posong or agong-ong in Kiniray-a and its flowers have a diameter of 45-65 cm. R. lobata is one of the few Rafflesia species that produce aerial buds and flowers several meters above the ground.

Aside from the Philippines, Rafflesia species are found in the forests of Southeast Asia, in Thailand, Malaysia, Sumatra, Java, and Borneo. A total of 28 species have been recognized so far.

A parasitic plant that lives inside the stem and root tissues of the host plant, Rafflesia species have no leaves, chlorophyll, stems, and roots. Only its flowers emerge from the ground, as a bud. It is dependent entirely on the host plant for water and nutrients. Its host plant is the Tetrastigma vine (Vitaceae), a tropical vine related to the grape family.

Rotten flesh

Rafflesia flowers range from red, reddish orange to rusty brown, with five petal-like structures filled with whitish warts of different shapes. They are either male or female.

When in bloom, Rafflesia’s large and fleshy flowers emit the odour of rotten flesh that attracts carrion-flies, its agent of pollination. But its bloom is short-lived, from three to five days.

Tree shrews, squirrels, rats, and other forest mammals eat its fruit, and its extremely tiny seeds are most likely dispersed by ants.

Our Rafflesia species

R. Schadenbergiana is the largest Rafflesia flower in the country, with a diameter of 0.8 meters. The largest known flower in the world is R. arnoldii, from Sumatra and Borneo, whose flower can reach up to 1.5 meters in diameter and weigh up to 11 kilograms.

R. Schadenbergiana is named after Alexander V. Schadenberg (1851-1896), of Breslau, Germany, who discovered it in 1882 in Mt. Parag, Davao. Since then, it has never been seen for more than a hundred years and feared to have gone extinct. It has been rediscovered in October 1994 in Cotobato by Pascal Lays, a visiting scientist from the University of Liege in Belgium.

Schadenberg was a chemist who managed the famous Botica Boie, then the largest drugstore in the country. He was also an ethnographer and a natural history enthusiast who collected insects and plants in the Mt. Apo area in 1881-1882. His collections, including photographs, are in museums in Dresden, Vienna, Berlin, and Leiden.

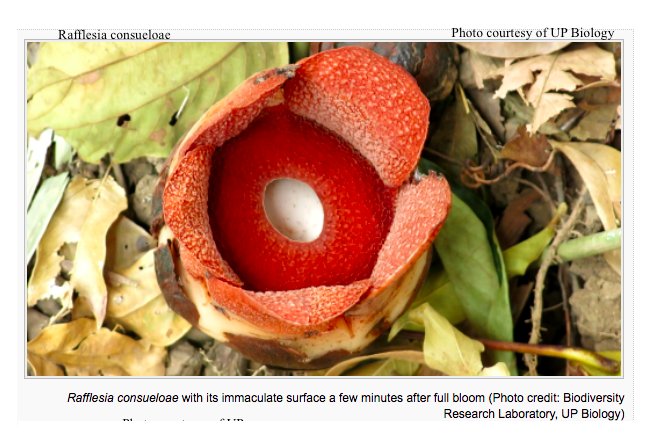

R. consueloae, discovered in Nueva Ecija in 2014 by a team of biologists from the University of the Philippines, is considered as the smallest among the largest flowers of the world, with an average diameter of 9.73 cm. In contrast to other Rafflesia flowers, its flowers do not have a smelly odour, and its fruits smell like that of a young coconut. It is the sixth species from Luzon and the 13th for the entire country.

It is named in honor of Consuelo Rufino Lopez, the wife of Oscar M. Lopez, chairman emeritus of Lopez Holdings and an advocate of biodiversity conservation in the country.

Discovery

The French explorer Louis Auguste Deschamps (1765-1842) stayed in Java for three years, as part of a French scientific expedition to Asia and the Pacific, where he collected a specimen of R. patma in 1797. During his return voyage in 1798, amidst the war between Britain and France, the British seized his ship and all his papers were confiscated. It was only in 1954 that the Deschamps papers were rediscovered in the Natural History Museum, London.

A British surgeon, Joseph Arnold, collected another specimen of a Rafflesia species found by a Malay servant in Sumatra in 1818 in an expedition led by Sir Stamford Raffles, the founder of modern Singapore. The generic name Rafflesia, in honor of Sir Raffles, was recognized in 1820 by the Linnean Society of London.

Constant threats

Seriously threatened with extinction, Rafflesia flowers are very rare with small and geographically isolated population. Critically endangered, Rafflesia species are under constant threat from widespread destruction and degradation of Philippine forests.

Habitat destruction includes logging, mining, slash-and-burn cultivation, conversion of lowland forest into farmlands, forest fires, and wildlife hunting. Other threats include the cutting of the Tetrastigma vines, and human disturbance in the guise of unsustainable ecotourism, or flower viewing by tourists.