BY ELIZABETH LOLARGA

THE Philippines has gone through a Victorian period where homosexual love, described as “the love that dares not speak its name,” was frowned upon and considered morally bankrupt.

THE Philippines has gone through a Victorian period where homosexual love, described as “the love that dares not speak its name,” was frowned upon and considered morally bankrupt.

Early in the 20th century, when photography became a way of leaving something for posterity, Filipino males, whether best friends, brothers, fathers and sons, teachers and students, classmates and even illicit lovers, flocked to photo studios and posed in various guises of affection that somehow got society’s nod.

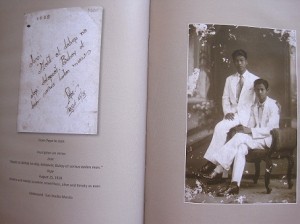

Compiled in a book entitled A Token of Friendship: Philippine Photos of Male Affection (published by Ige Ramos Design Studio) by John Silva, these photographic evidences that were bought, even saved, from flea markets and junk shops by collector Jonathan Best serve, 100 years later, as “cultural documentation and, more importantly, as reminders that the gestures of affection line our personal histories, genetic markers in the pages of Philippine history,” Isa Lorenzo wrote in her foreword.

The photos and dedications behind the postcards, written in pencil or fountain pen, may seem cheesy and saccharine by the standards of today’s generation used to Twitter and other modern, shorthand applications that require just a few characters to convey a thought or feeling.

Back in the restrained years before gay liberation and the sexual revolution, Silva wrote, “photographs captured the expressed affection of men, with a restraint coinciding with the period.”

It was common for a man to write to a fellow man with almost elegantly calligraphic flourish at the back of a photo, “May your heart be a flower pot, where I may plant the word Forget-me-not.” Or in pure Filipino, “Maliit at dahop na alay, datapwat, buhay at sariwa kailan man (Petite and needy souvenir, nevertheless, alive and timely forever).”

It was common for a man to write to a fellow man with almost elegantly calligraphic flourish at the back of a photo, “May your heart be a flower pot, where I may plant the word Forget-me-not.” Or in pure Filipino, “Maliit at dahop na alay, datapwat, buhay at sariwa kailan man (Petite and needy souvenir, nevertheless, alive and timely forever).”

The photos are divided into “Solo Images,” “Couples” and “Group Poses.”

Silva observed that the gestures of affection captured in the chapter on couples include “shoulders pressed against each other, heads inclined toward one another, holding of hands, the hand or the arm resting on the other’s thigh, arms around waists, and arms resting on shoulders. More intimate photographs show men standing to the side and behind with the other seated, the former having his arms encircling the other.”

Another observation is how the clothes the men wore signified how they’ve risen in the world. But don’t be deceived by the three-piece suits. According to Silva, these suits “were mostly worn by Filipinos working in the United States as domestics, cooks, cannery, and farm workers.” They suited up to impress the folks back home.

And when a couple was in almost identical suits, one man should wear a bowtie, the other a tie to make each of them distinct.

Even if two men posed as a pair, it did not immediately connote a homoerotic relationship. It could be plainly platonic, the men brought together and bonded by their duties to country as Philippine Scouts, Constabulary, Army or Navy men.

Or the lads wore kimonos as parties with a Japanese theme were in vogue in the 1920s. There is a rare photo of a priest and a novitiate in their religious habits; the inscription at the back wishes the receiver of the postcard a happy birthday.

These personalized postcards, especially the ones with solo images, were also used as calling cards or cartes de visite “to introduce oneself to business prospects or to society,” Silva wrote.

Group photos, showing three men or more, showed more lightness and camaraderie. In a group, the subjects seemed freer in displaying affection, most especially when they joined holiday outings to Antipolo, Tagaytay and Baguio.

“These photographs showed the happiest of faces,” Silva wrote.

The restraint in most photos was part of their charm. In his epilogue, Silva noted that the sexual revolution “eased, if not eliminated the last restraints on open displays of affection…What was once heartfelt but ambiguous could now be openly expressed. There would be no more doubts as to the meaning of solid embraces and outright kisses between men in gay enclaves and pride marches.”

And here lies the book’s value—the storing of “visual memories of loves suspected, hidden and dismissed, but not forgotten.”

In a way, the book is empowering for men still in the closet. When it was launched at Silverlens Gallery in Makati City with a month-long exhibition and weekend talks by the author, he saw gay friends bringing “their straight friends to the show (and vice versa) with the intention of coming out. They did, lots of happy tears.”

Still, there is nothing like the mystery and intensity in an inscription behind a photo, saying in Spanish: “Para ‘Palaspas,’ el erotico de suaves es dulces parrafos, en prueba de admiracion (For your hands to be busy with, you sexy, sweet talker, proof of my admiration).”