From Pineapple to Piña: A Philippine Textile Treasure is an exhibit on a variety of vintage piña clothing from the collection of Lacis Museum of Lace and Textile at the SFO Museum, San Francisco International Airport. It runs until November 13, 2022. See it online, https://www.sfomuseum.org/exhibitions/pineapple-pina-philippine-textile.

One of the oldest traditions in the Philippines is textile production from the Cordilleras to Sulu and Tawi-Tawi with its communities of hand weavers and their distinctive weaving techniques that constitute their heritage and identity and the nation as a whole.

The pineapple

“A beautiful lady with a hundred eyes” is a riddle familiar to us. The pineapple, indigenous to South America, is one of our “fruit immigrants,” introduced in the late 16th century during the Spanish colonial period.

Today, the Philippines is one of the main exporters of preserved and fresh pineapple products; it is also the only country that uses pineapple leaves to create piña textile— a fine and diaphanous cloth with its off-white sheen and luster.

Piña

A particular type of pineapple with long leaves that measure from 0.5-2 meters, the Spanish Red variety has been cultivated in Western Visayas and harvested exclusively for piña fibers. Historically, piña weaving has been rooted in Kalibo, Aklan and, Aklan continues to be the center of piña production.

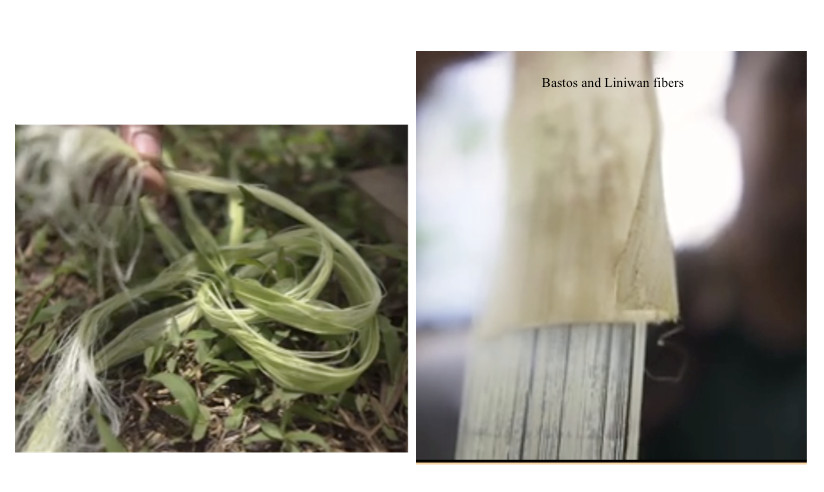

It takes 18 to 24 months to harvest mature pineapple leaves by hand. Its thorny sides are first stripped off and two kinds of fiber are extracted from the leaves. The first is called bastos, the initial fiber scraped of its outer coating with a broken plate; it is a strong and coarse fiber used for making string and twine. The second layer, liniwan, is scraped with a coconut shell, and its much finer strands are used for weaving piña cloth. The fibers are cleaned of its sticky gum, pounded, and washed repeatedly in running water, usually in rivers, and dried under the sun.

Then, each fiber is knotted by hand (pagpisi) with the utmost care so that the fibers do not break; continuous strands are formed and trimmed into one long continuous strand (pagpanug-ot). The piña filament is warped and spun into spools (pagtolinuas). The final stage involves weaving (paghaboe) on an upright foot-operated two-treadle loom. Until today, the processing of piña is all done by hand.

A finished piña cloth comes in three different widths: 24 inches, the shortest; 29 inches, and 31-32 inches, all depending on the set-up of the loom during weaving. In adding color to the cloth, natural dyes from leaves, flowers, and trees are usually used.

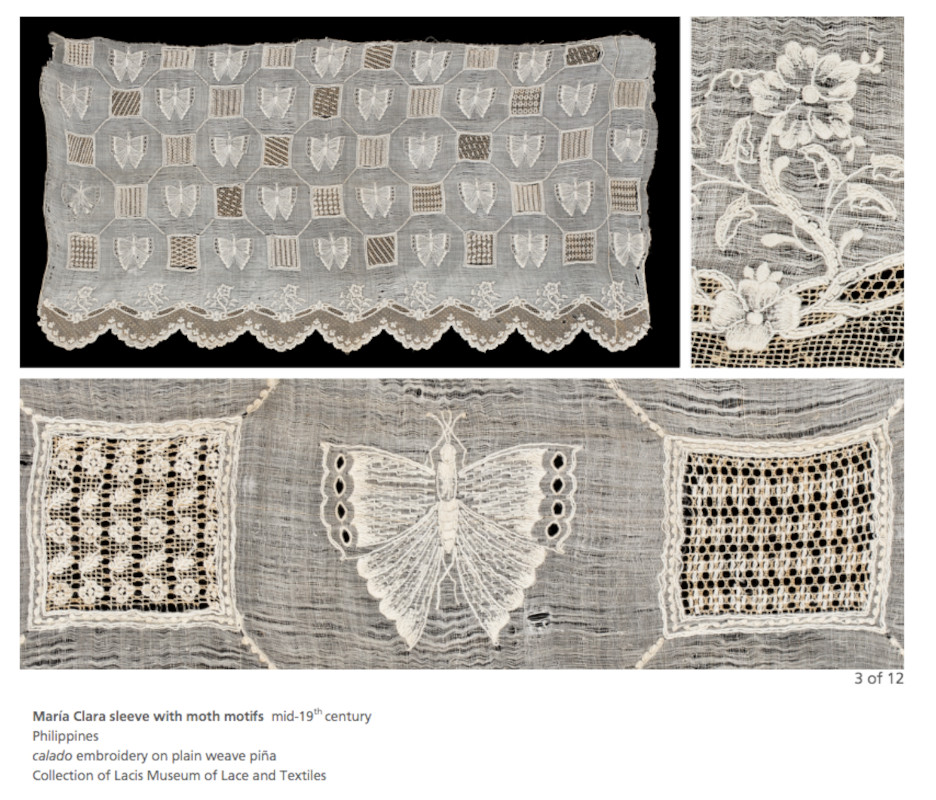

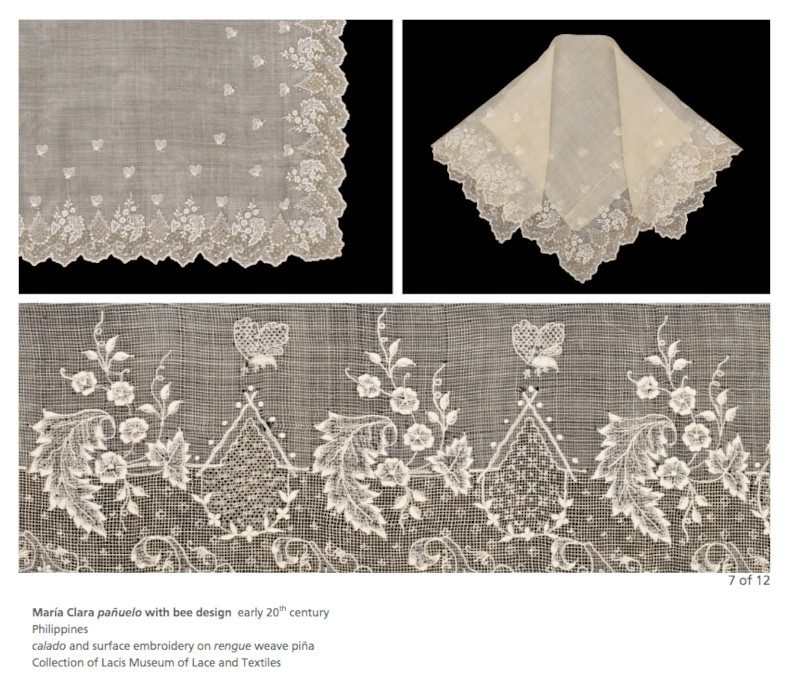

Embroidered piña with intricate designs, delicate and durable, is made into barong tagalog, baro’t saya, traje de mestiza clothing, and women’s kerchief or pañuelo, traditionally worn by wealthy Filipinos.

History

Historically, Panay has been the center of native textile weaving from the mid-1800s to early 1900s, mostly piña, jusi, sinamay, abaca, and other local fabrics. The British Consul Nicholas Loney, in his 1857 travel to the island, had noted that almost every family in Iloilo owned a loom for weaving.

The 19th century was Panay’s golden age of weaving from pineapple fibers. Tedious and laborious in its making, piña was considered a fabric fit for royalty. A luxury export, it was worn by European aristocracy in the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1887, an embroidered piña garment was dedicated by Don Epifanio Rodriguez of Lucban, Tayabas to the queen regent Maria Christina of Austria, and the queen consort of Alfonso X11 of Spain.

Las bordadoras

Under Spanish rule, convent schools (beaterios) and orphanages (asilos) were established all over the country where young Filipino women were taught needlework, from basic stitches to intricate embroidery, among other domestic skills as a prerequisite for married life. Filipino artisans earned prizes in competitions, local and international, and accolades for their outstanding work in embroidery. Most fabric is embroidered mostly in Manila, Lumban, Laguna, and Taal, Batangas nowadays.

Types and motifs

Piña handwork includes calado (open work) where selected threads are pulled out from the cloth and the remaining threads are embroidered with a variety of design. Sombrado (shadow work) is a type of appliqué where pieces of very fine fabric are inserted into designs with the edges carefully stitched into the fabric.

Design motifs include flowers, leaves, vines, butterflies, and birds, all usually left entirely to the imagination and creativity of the embroiderer and the weaver.

Contemporary piña is often blended with silk (piña-seda), and other fibers. Overall, the sustainable production of piña is organic and free from chemicals, from the planting of pineapples to its end product, a piece of piña clothing.