By MA. THERESA ANGELINA QUINTANA-TABADA

IN the dead of night, two creatures square off for the undying soul: the mortal and the immortal.

Myke U. Obenieta is both: blogger and sundered citizen of the Filipino diaspora.

By day, Obenieta juggles life as husband of middle school teacher Arlaine, 37, and father of Aegan, 10, and Golli, 7, in Topeka, Kansas, while studying Sociology and Mass Media at Washburn University.

He emails an English column, “So to Speak,” twice a week to Sun.Star Cebu, and a weekly column in Cebuano, “Pungko-pungko,” to Sun.Star Superbalita. Both columns are in the Sun.Star website of regional papers.

But it is as a nocturnal blogger that Obenieta, a longtime insomniac, finds the space to spread his wings like the manananggal, a bloodsucking creature from Filipino myth that has become a favorite metaphor of his.

Although he runs two personal blogs, another on international journalism, one on Asian cinema and a fanzine devoted to the Brillante Mendoza film, “Thy Womb,” Obenieta is better known as the moderator of “Kabisdak,” an online lighthouse for lovers of the Bisayan language.

Obenieta posted the first poem on Dec. 19, 2008 at 4:10 a.m. “Dili katam-is ang mohasol sa tanlag (It is not the saccharine that will stir the conscience)” was written by Vicente Vivencio Bandillo, a Cebuano poet turned diplomat, writing about the homeland then from Dubai, United Arab Emirates.

On Feb. 26, 2013, Obenieta posted the 2,825th poem, Urias A. Almagro’s “Hubad sa balak ni Pablo Neruda (Translation of a poem of Pablo Neruda).” A physician who left Cebu in the 1970s, married an American and raised a Fil-Am family in New Berlin, Wisconsin, Almagro persists in writing in Cebuano—306 poems posted on Kabisdak to date—despite a lack of local audience and zero chances with American publishers.

In 2011, the Cebuano (Binisaya or Bisayan)-speaking natives of Cebu, other provinces in Central Visayas and some places in Mindanao were among the 2.2 million overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) estimated by the National Statistics Office.

In his May 15, 2008 post on breezymyke.blogspot.com, Obenieta called for contributors to the Kalihokan sa Bisdak nga Katitikan (Movement for Cebuano Literature), his “battle cry against the cold-blooded spawn of alienation spelled triple in scarlet letters: KKK (kalaay, kalimot, kamingaw).”

Boredom, forgetting, loneliness.

Not all of Kabisdak’s 87 contributors fear this terrible trio. For Cindy Velasquez, 26, alienation from self is worse than physical dislocation.

Growing up in Daanbantayan town in northern Cebu, Velasquez turned to writing for lack of friends. The lecturer on Literature and Humanities at the University of San Carlos in Cebu City said she found her voice after a Cebuano Literature assignment led her to Obenieta’s poems.

Two days after reading his poetry, Velasquez wrote her first Cebuano poem.

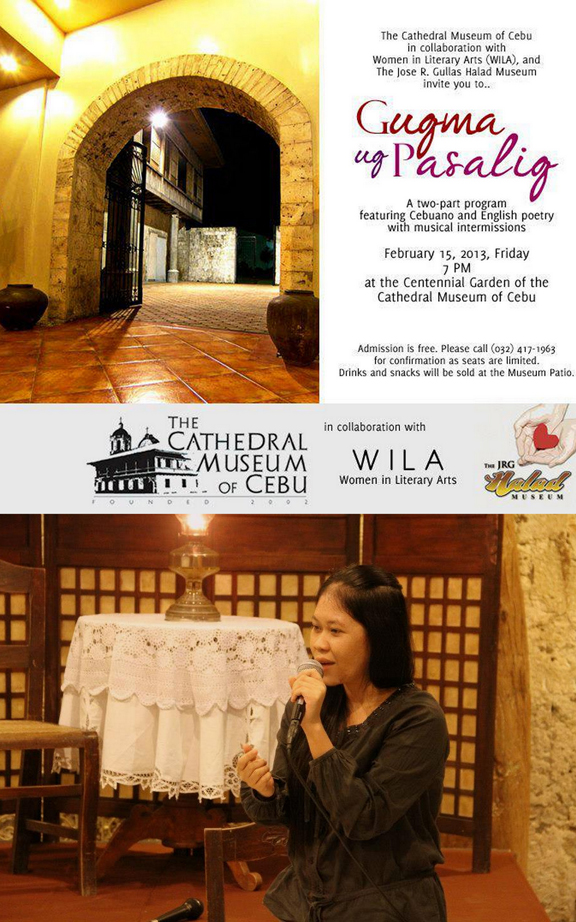

A member of The Nomads, young poets from Visayas and Mindanao that meet every month to read and perform poetry at the La Belle Aurore Bookshop, Velasquez is proud that the Kabisdak blog is home to women’s voices.

“I feel I’m in the right place. Not just because the site encourages us to return to our local tongue. There is this sense of security of expressing myself,” she said.

If Kabisdak has met its creator’s longing to create a sanctuary for the dispossessed, it must be because since childhood at Quiot Pardo, a barangay in Cebu City known for singers like Dulce, Obenieta was already familiar with disconnection and estrangement.

“My mother had the misfortune of being one of the daughters of an illiterate woman who believed that girls need not be educated because they would end up as housewives anyway,” he said.

Violeta married Severiano, whose dream of becoming a lawyer was, according to his son, “sidetracked by his appetite for alcohol.”

Despite this nest of failed dreams, Obenieta remembered growing up in a home awash with stories: from the Bisaya Magazine comics and radio drama serials that his mother was devoted to, from the political commentaries that his father tried to drown out in one-man shouting matches with the radio, from the news articles and poems like “Invictus” and “Desiderata” that Severiano demanded his children read and memorize.

From elementary through high school, Obenieta cut classes to be with his newsboy friends in Lorega and T. Villa. To kill time, he read the papers he was selling. Newspapers became his gateway to a love affair with books.

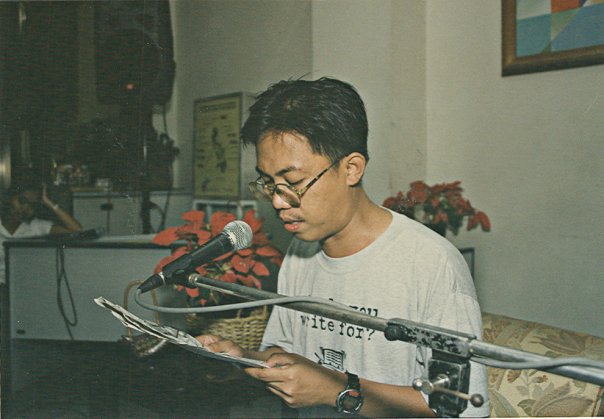

In college, Obenieta started writing for Sun.Star Weekend Magazine. Poet Erma Cuizon, on her first day as Weekend editor, remembered reading Obenieta’s works from a portfolio sent by young writers.

“In his writing I saw his aching need to move on to the next personal writing chapter of his writing skill. And this was what surely moved him to write and write, and never to give up,” Cuizon said. “Sometimes his language sounded like the translation into English of a work in good Cebuano (yet) he never stopped trying.”

“Persistence pays off,” Obenieta said. In 1999, during the Fort San Pedro launching of a business/lifestyle magazine he was editing, he noticed his program emcee looking distraught. Arlaine Jayo had lost an heirloom earring given by her mother.

Although he had drunk more than usual to escape talking to the guests and was trying to sneak out, Obenieta spent the next hour or so of the evening on his knees, combing the lawn—and found the earring. Three years later, he married its owner.

Like Violeta, Arlaine grew up “devouring” Bisaya Magazine “from cover to cover.” She said Obenieta, her first and last boyfriend, resurfaced her grade school love of written Cebuano.

“I never would have the confidence to write if not for his support.”

In July 2006, Arlaine left for Topeka, Kansas to handle special education students there. Obenieta and sons Golli, 4, and Aegan, 8 months old, stayed behind.

When they joined her 10 months later, Aegan clung to his Dada and refused to look at his Wawa. It took a month for mother and son to bond again. Squeezed by work, motherhood and graduate school, Arlaine said she is still looking for space to write again.

“It’s writing that sustained (Obenieta) here,” she said. “Leading a very domestic life here in the US would have been a struggle if not for his passion to read and write. It is easy to succumb to depression.”

In “Holidiaspora,” a Dec. 3, 2011 poem posted on Kabisdak, Obenieta used the manananggal to personify the OFW’s struggle to reconcile intertwining but opposing longings like their levitating torso and earth-bound lower limbs.

The poem closes with: “Pauli na intawon, minahal nga manananggal (Please come back home, beloved manananggal)!”