By NORMAN SISON

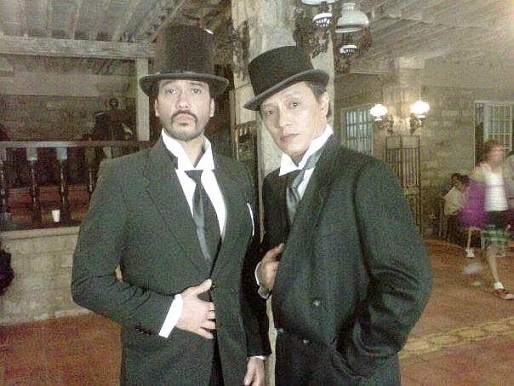

RONNIE Quizon may be a fan of Andres Bonifacio, the father of the Philippine Revolution, but he immediately snapped up the offer to play a role in the big-budget biopic about Bonifacio nemesis Emilio Aguinaldo, the Philippines’ first president.

“As a whole, I thought it was a no-brainer. I would love to be a part of such an ambitious project,” says Quizon of El Presidente , one of the offerings in this year’s Metro Manila Film Festival. “And I think it can be considered as a milestone in Philippine movie-making someday. I can only think of two words: epic proportions.”

Of course, that will be for the audience to decide. Movie budgets alone don’t win accolades. There is no award for having the largest movie budget.

One thing is definite: El Presidente (“The President” in Spanish) will get people talking about Aguinaldo’s place in the nation’s history. Making a movie about a historical figure is one thing. Telling history as it happened is another.

The debate over Aguinaldo has been going on since his election as president of the newly born Republica Filipina on March 22, 1897 at the Tejeros Convention, in which Bonifacio was deposed by Aguinaldo followers as the leader of the revolution. Bonifacio declared the proceedings null but he was liquidated after a kangaroo trial.

The Aguinaldo controversy deepened in 1899 with the murder of General Antonio Luna, the chief of the nascent Philippine Army, by officers and soldiers loyal to Aguinaldo.

Even today, in true Filipino fashion, the discussion over Aguinaldo can get as heated as the intramurals between the Aguinaldo and Bonifacio factions at Tejeros — minus the drawn revolvers, of course.

“There will always be a debate on Aguinaldo’s part in our history,” says Quizon, son of the late Philippine comedy king Dolphy. “Everybody’s a critic, as I always say.”

Quizon is an admirer of Bonifacio, firstly, because he is a Manileño like the Supremo and was born on November 29, a day short of Bonifacio’s birthday. “I fondly remember that I can have parties on my birthday and not worry about the next day since it was a holiday,” says Quizon, who turns 47 this year.

Secondly, there is Aguinaldo’s historical record to reckon with.

Secondly, there is Aguinaldo’s historical record to reckon with.

Quizon plays Apolinario Mabini, Aguinaldo’s chief political adviser, in El Presidente. Mabini was critical of Aguinaldo’s leadership. Although he needed Mabini’s talent, Aguinaldo often ignored his advice.

In his unpublished manifesto, La Revolucion Filipina(“The Philippine Revolution”), he blamed Aguinaldo for failing to consolidate the gains of the revolution against Spanish colonial rule and for losing the Philippine-American War (1899-1902), which erupted when the United States ignored Filipino aspirations for independence and annexed the Philippines. “To sum it up, the Revolution failed because it was badly led,” Mabini declared. The Philippines became independent in 1946.

Mabini died of cholera at the age of 38 when an epidemic hit Manila in 1903. His friends published his manifesto in 1931.

Mabini is a key figure in the founding of the Republic of the Philippines. Polio made him a cripple but he towered over everyone with his intellect.

A lawyer by profession, Mabini outlined the Philippines’ first constitution. He was appointed prime minister and concurrently foreign affairs minister in Aguinaldo’s cabinet, making him the father of today’s Department of Foreign Affairs.

Despite his contribution, however, Mabini is often relegated to secondary honors in the pantheon of Philippine national heroes. Most Filipinos readily think of Jose Rizal, Bonifacio and Aguinaldo when asked about the revolution.

“The thing that strikes me the most is his preference to stay in the sidelines, keeping a low profile,” says Quizon about his research on Mabini’s character. “That was hard, mind you, since he was an almost reclusive man.”

One American author described Mabini as “an amiable intellectual” but painted a more human picture. “Lean, dour and frequently tactless, he was a theorist often unable to deal with practicalities,” wrote Stanley Karnow in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines.

One American author described Mabini as “an amiable intellectual” but painted a more human picture. “Lean, dour and frequently tactless, he was a theorist often unable to deal with practicalities,” wrote Stanley Karnow in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book In Our Image: America’s Empire in the Philippines.

Mabini’s view of democracy stemmed from the American and French revolutions, declaring that the government should faithfully interpret the people’s will. Filipinos today romanticize him as the “brains of the revolution.” But, in his day, rivals dismissed him as Aguinaldo’s “dark chamber”.

The political elite dominated the Malolos Congress, the Philippines’ first elected legislature, named after the country’s revolutionary capital north of Manila. To Mabini, they only looked out for their own interests.

“They had no intention of sharing either political or economic power with the peasantry,” wrote Brian McAllister Linn in his book The Philippine War 1899-1902. In the end, Aguinaldo dismissed Mabini in 1899 and sided with the political ruling class.

Mabini had warned Aguinaldo when war broke out with the Americans: “We cannot conquer today, but we can hope to achieve victory tomorrow if the people are with us. If not, we will be defeated.” Aguinaldo was captured by the Americans on March 23, 1901.

“I just hope people learn what they can from the debate over Aguinaldo and continue improving their lives and from thereon. By doing that alone, they might help improve our nation in the process,” says Quizon.

As to how El Presidente will land in the annals of Philippine cinema — just like in Aguinaldo’s case —history will be the judge of that.